|

||||||||||||||

| As told to her son Paul Roberts in 1995 |

||||||||||||||

|

Starting Work - Doris Watts

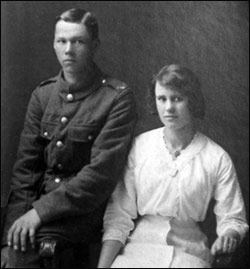

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

1. INTRODUCTION My family background was boot making. All the family was boot makers; shoemaking came in later. It was always boots. Women’s and men's work was always a boot; women in those days wore a high boot that that laced up the front.

Dad was a skilled boot maker from Lavendon3. I once had an upset at work in my early days and he told me "Don't come home bawling, tell them they don't have all the work". From the beginning I could stand up for myself in a factory. I remember once my sister Elsie had a disagreement with a forewoman and Elsie told her "I would rather sing in the streets for pennies than work for you another minute." Elsie then had a war invalid husband who could not work and two children. That was the Watts' pride. Grandma and her second husband (Old Bill) had lived at Irthlingborough after moving from Wellingborough4. Mum was a small person; had the job of carrying the finished boots as a child all the way from Irthlingborough to Fred Knight's factory in Park Road, Rushden. Fred Knight was a kindly man and one day he said to mum "Rose, you have no business on this job, they are not to send you any more”. It may be this that brought grandma and ‘Old’ Bill to Cromwell road5. What boots mum carried I do not know. I presume they were the common boots and that they were uppers lasted and finished. Perhaps Grandma machined the uppers. Mum recalled that once as she crossed the river from Irthlingborough to Higham Ferrers she saw a dead man floating in the water6. (In telling this to my son Paul he recalled that I had fetched and carried the work for my father7 from Charles Denton's factory in Higham Hill as a child and that when I had done 'lift dobbing8" for Mr. Lawrence and later Ernest Chambers at Raunds he had fetched the work for me.) When I started work at George Selwood's old factory in Harborough Road Grandma got me the job. The forewoman was Mrs. Knight. Her daughter also worked in the closing room. At the back of my mind are grandma working for Fred Knight and Mrs. Knight the forewoman and Grandma getting me the job. It is all somehow related. Grandma had been one of the earliest forewomen in her day. All her family, the Goosey's, were boot makers. When I started work grandma gave me her hand-closing hammer. This was for hammering down seams. It had a flat bottom and was made of small pieces of iron moulded into a band hammer shape. Because of the flat bottom it was no use on light leather. Later the curved hammer came in. Some years ago I presented Grandma's hammer to the Museum at Northampton.

Old Bill's brother was Charles Denton. For many years he also had a shop at the bottom of Higham Hill opposite the traffic lights. Both brothers had been born in one of the houses that stood at the Walnut Tree in the North End of Higham Ferrers. Charles Denton's factory was a large shed behind a shop that was later Gramshaw's, the furniture people. This was on the right side going up the hill. I used a truck, which was a box on two wheels, to take Dad's work to Charles Denton. How mum carried the work from Irthlingborough I do not know. My first job when I left South End school at 13 years of age on the I7th November 1909 was at Selwood's old factory in Harborough Road9. In all I worked in 7 Rushden factories in 14 years until I married and came to live at Raunds. The change from Rushden to Raunds was great, but that is a chapter on its own. 2. Selwoods Skiving at Selwood's was still a hand job. The skiver would use a sharp knife on a marble slab. The work at Selwood’s was medium light work. I was small and could only just peep over the bench. Even today I can recall Nell Parker, one of the women hand skivers. Later Nell married a Mr. Patenall. The forewoman was Mrs. Knight; she was a tall woman. The clicking room foreman, I forget his name, was a nice chapel man. On Valentines Day all the girls in the closing room sent him, through the post, a pair of ladies pants. I was appalled at what his wife thought, because underwear was not a thing mentioned. The girls thought it great fun. They would sit at their work giggling away. Despite the long hours shut in a shoe factory all day, the girls never lost their sense of humour. The hours were from 6am to 6pm with an hour off at midday when we all went home to dinner. On Saturday we worked until 12 o’clock, when we were paid. My hours, as a starter, were from 7am to 5pm. I cut off the ends and also tied the ends, for which I was paid 3/6 per week. I was very quick at the work and whatever job I soon picked it up. The tied ends were 1/8th of an inch. Grandma said when I told her, that would not have done for her in her day; the ends would be tied 1/16th of an inch. I gave Mum my wages and she returned my six pence. This was an enormous amount of spending money. It had not been many years before when I had to go and ask Grandma to lend Mum sixpence one Tuesday because we had no money left for food. I can still hear Grandma shouting at me "Where does our Rose think I can get a tanner from on a Tuesday". As I ran down the entry, the front door opened and Old Bill came out and said " Give this tanner to our Rose, but don't tell your Grandma". I worked at Selwoods for six months. I left in the summer to be nearer home for dinners in winter. 3. Robinson's My next job was at Robinson's factory on the corner of Roberts Street and Grove Road. I asked for another six pence per week when I went. I was then paid four shillings a week. I went for the same job, knot tying. A friend of mine, Mable Weedon, with her increase put a penny a week up which she later increased to two pence. This money she intended to use to emmigrate to Canada. A lot of people seemed to emmigrate to Canada then10. Mr. Robinson lived further along Grove Road and I cannot remember ever seeing him. His son came to the factory. He had ginger hair and I thought him smashing [goodlooking]. A sister, who never married, kept house for Mr. Robinson. Some fifteen years ago my husband's sister entered a Home for the Elderly at Olney. One Saturday I visited her and to my great surprise Miss Robinson sat in the lounge. I introduced myself as having worked for her father. Miss Robinson said with dignity that she was in the home because it was so difficult to get servants. We had quite a chat about old Rushden and the old pre 1914 days. I had a gathered [infected] finger one-day. Putting my hand inside the boots to tie in the laces caused me great pain. The woman charge hand of the section said I was too slow. I said that I had a gathered finger and started to cry. The charge hand called me a 'lazy bitch'. Flo Robinson, one of the Harborough Robinson's, said 'leave the child alone'. Ada Pettit, the forewoman, who lived in Portland road, came down to see what the commotion was about and I showed her my finger. Ada spoke kindly and asked if I could rub down backs. I grasped the heavy handle with my hand and found that I could rub down easily without hurting my finger. So I completed my day’s work without having to go home. Later Ada put me on putting in side linings. This was another step up. One day the girls came out on strike over the charge hand. The strike lasted only a couple of hours. And I never knew the result. I left after that and went to work at Cave's factory. I was just 15 years old then. 4. John Cave & Son

The tragedy of Paul Cave's suicide, when he gassed himself in the office, was still the big topic of talk. This had occurred whilst I was still at South End School. A girl in the Closing room had worked there when Paul Cave committed suicide. She told us the she had heard the gun go off, when he shot himself11. One day, with another girl, I went into the lavatories at work and we rearranged our hair so that we looked older. Coming out I noticed that the other girl was bleeding down her neck where I had accidentally stuck a pin in her flesh. The girl seeing the blood screamed. This brought the forewoman, Mrs. Sharpe. I was threatened with being sent home. However Mrs. Sharpe changed her mind and put me on another bench further in the room. with older women. One of the women was Mrs. Tew, the other was Sarah Tibbit. When we sang the song ‘Don't go down the mine Daddy’ Sarah's eyes would fill with tears. So for fun we would sing the song to make Sarah cry12. Despite the hard work we could always find time for mischief. Even now I recall the first verse of the song. Don't go down the mine, Daddy. One of my jobs was helping the beader; beading was still a hand job. The lining was stitched to the outside and the eighth of an inch was solutioned, turned down and then stuck down. As Clara Hatfield turned over the edge, I used grandma's hammer to hammer down the seam. One day I was faster with the hammer than Clara was with the solutioning and turning down, and I hit her thumb. She turned a ghastly white and I thought that she would faint. She just managed to murmur "Oh". Later Clara emmigrated to Canada. Another girl had a bad affair with her boyfriend. Clara kindly took her with her to Canada to start a new life. Clara Hatfield was one of the many nice, kind women I worked with. As we were working we would sing. I had a decent voice for singing and once won signing prizes. I loved to sing as I worked; Sal Sharpe, of Queen Street, was the forewoman and one day she called out "Doll, if you don't stop that row you'll have to go home". I was offended; but Sal recognised my quickness and put me on a machine. For a time I was put in the clicking room punching caps. One day one of the men said something dirty to me. Sos Coles, a very nice man, said "Doris never have anything to do with them, they are not nice men". Sos Coles' father was an insurance man. Mum had to see him about insurance. Two men in the office, Mr. Cox and Mr. Newton left the firm at the time. Sal Sharpe went with them as forewoman. They started up “Coxton” in Rectory Road 5. Jimmy Hyde’s We always called the firm Jimmy Hyde’s. The factory was in Windmill Road. I cannot recall Jimmy Hyde; he had a sister, and a brother Bill Hyde. They lived at the ‘Limes’ Higham Road. Bill Hyde was the man who would come and put the belts on the machines when they came off. The mechanic was Dennis Smith; he could mend the machines when they broke down. The girls were marvellous to work with; they supported each other and stood by anybody in trouble. Some of the girls were going on a train trip to the Nottingham Goose Fair. I went to the station to see them off on the one o’clock train. Such outings were beyond me. I never saw the sea until I was 22 years old. One of the girls said to me "I've got my best shoes on, I only need to put on my best stockings and then I am ready to go". Puzzled I said that I could not see how that helped and she would have to take her shoes off to get her stockings on. The girls howled with laughter at my innocence. They were all great fun. At this firm I was paid 5/- per week, which I asked for when I applied to work there. It is now that I bought, for 4/6, the first fowl for Christmas for the family. Life began to change for me now. You could buy a good pair of new boots from the firm and they stopped the cost at 6d per week from your wages. I bought a smart pair of Glace Kid boots that laced up the front and then had three hooks. They cost me 6/6 and they stopped me 6d per week out of my wages to pay for them. At this time bought myself a Singer sewing machine from the Singer Sewing Machine Company shop in Church Street. This cost me £10, which I paid for over two years. For £11 I could have had a tabletop model but the extra was just a bit too much money. I tell this story with my machine by my side; I still have it. I now discover that I have a flair for dressmaking, so I bought patterns or copied fashions and made my own clothes. From that time I also made clothes for the family. We had a strike at Jimmy Hyde’s. The girls came out; I think that it was over an elderly charge hand. Three of we younger girls went up to Knuston violeting. I had just collected a lovely bunch of violets when ‘old’ Newsome, who lived in the farm opposite Knuston Lodge Gates and shouted at us. He had a voice like a foghorn. Frightened, we three bolted up the road to Irchester and had to return to Jimmy Hyde’s via the field path to the Wellingborough Road and Sanders' Lodge. When we got back, the strike had only been a short one. Next morning I had to go into the office and explain my absence. This was now 1913 and the Trade (Union) came in and we all joined. I had to go home and bring back a paper, which I suppose was my birth certificate. History was now made because from now on they had to pay you a set wage; you did not have to ask. I was happy at Jimmy Hyde’s but moved to Coe and Green in Newton Road, to be nearer home. Dad also worked at Jimmy Hyde’s while I worked there. What he did I do not know. You could always see his tall figure when you passed the Lasting room. When I first saw him working I looked backwards to see if he had seen me and fell into a sack of leather head first. On hot summer days I would take a packed lunch that Mother prepared and would sit with the others on sacks outside eating my lunch. 6. Coe and Green I cannot recall the war’s starting. Somehow I decided to be nearer home. This is how I came to work at Coe and Green’s. Tom, who had been in the Redcoats pre-war, was now called up in the Territorials. I think that he was in a camp at Thetford, but I cannot be sure. Mum and Dad visited him and stayed in lodgings there. It was left to Elsie and me to look after the others in the family whilst they were away. I seem to think that the firm had not been long started up. (My son Paul worked in the building in the 1950's, when it was Lawrence Shoes, and he can describe the layout of the factory in Newton Road). It was opposite the top junction with Cromwell Road and behind the large house where Maud Percival lived. Mr. Coe was a large man with a loud voice; Mr. Green was related to the Greens of William Green and Co. He was a very mild mannered man and lived in a large double fronted house in Queen Street. The skiving machine was a Marvel. The war cut off the supply of German steel that was used to make the blade. We had to use inferior British steel, which was soft, and the knives then only lasted a few weeks. I remember going up to the clicking room and telling Mr. Coe that I must have a new knife. In his loud voice he said " Doris, you will have to make do". I told him that he had better do the job himself. I turned my back and walked away, expecting a dagger in my back at any moment from the angry Mr. Coe. No one talked to Mr. Coe like that. But Dad had drilled it into us to stand up to them. I got a new knife.

When I went up to the clicking room foreman and showed him the spoilt back he swore at me. My pride rose and I hautily told him that “I was not swore at at home and I would not be swore at here”. Ernie Adams, who stood behind the foreman, sniggered out loud. He knew what it was like at home. Ernie later married my cousin Laura Watts, Uncle Jack's daughter. It seemed that at Coe and Green we did mainly good quality civilian work. The Russian boots are the only heavy army that I remember working on. The girl on the crimping machine got her finger in the works and had her finger end cut off. They took her to hospital but left the finger end on the machine all day. You could not help but notice it. I went home and told Mum and said that it made me feel ill. Mum got out the Epsom Salts and gave me a dose saying that they would make me feel better. Yet I was unhappy at Coe and Greens. It was the first firm that I had been unhappy working there. I could not get on with Mrs. Swannell, the forewoman. If anything was wrong I felt that she picked on me because I came from a large family and were poor. I had this chip on my shoulder because we were poor. On the first Armistice Day in 1919 the engine stopped for the two minutes silence. I bowed my head and the horrors of war came flooding back. (Tom had been killed in France and all the boys that I knew). I did not want to go home because I knew Mother would feel the same way. The forewoman slapped me on the back and said "Cheer up”; I looked at her with tears in my eyes and she looked at me in astonishment. She said to the other girls “I never knew that she cared". Like Mum I hid my grief from other people. Whilst we were at the firm we had a day's outing. We went by train from Rushden station to Leicester. This was my first outing ever. I forget when it was. It must have been after the war; I cannot be sure. On my return Mr. Coe came after me and said "Doris, here are your presents, you left them on the train. I kept my eye on you just in case you forgot them". I must have been about 21 years old then. Because the forewoman seemed unkind to me and I had this chip on my shoulder, I handed in my notice to leave. Mr. Coe said "Dos, you’re leaving home you know"13. But I never said the cause of my unhappiness. Like I said, I had this chip on my shoulder. 7. The Co-operative Boot Factory I was on skiving at the Co-op and got on very well. I was fast and could do the difficult jobs; jobs that had many parts and were difficult to skive. You got more money on the lighter and better jobs than on the difficult ones, but that was the price of being fast and able to do any work. The work was of good quality and fine leather. The forewoman was Maude Percival. She lived in the large house that stood in front of Coe and Green's factory in Newton Road. The skiving machine was a 'Fortuna'. This operated with a right hand feed; I could work and have a book in my left drawer which I could read at the same time; much to the displeasure of Maude Percival. But I loved reading and still do so. I worked with Win Chettle and we were very good friends. Violet Cooper also worked in the Closing Room. Later Violet married Harry Hall of Raunds. Harry worked at Adams’ factory at Raunds with my husband. So when I married and lived at Raunds, because she was one of the girls from Rushden we kept up friendships. Later on, other Rushden girls married Raunds men14. Win Chettle and me both had an embarrassment. Mine was my large family of little brothers and sisters. Hers was that if she took home a boyfriend, her family would have either have a Pluck Pie on the table or a sheep's head, both of which her family enjoyed. We were both growing up and we felt dragged down by our families. Win Chettle was tall and disliked being reminded of her height. We would both confide in each other and have a good laugh over our mishaps. If we got into trouble it was because we got into mischief15. Work fell short and we went onto half time. A number of girls left the Co-op to go elsewhere. Eventually I left to go to the Premier. The Co-op had a rule not to take you back once you left, but some were taken back when work picked up. I did go and ask for a job later but was refused. I was annoyed with myself and my pride hurt for belittling myself and asking to go back. Some years later I was going down Newton road to catch the bus to Raunds from the Lightstrung16 with Paul in the pushchair. Passing Will's shop at the bottom of Newton road I bumped into Maude Percival coming round the corner from the High Street. She was pleased to see me and I said to her that I was now married and living at Raunds. Maude said that she was so pleased that I had married. 8. The Premier17 Conditions at the Premier were very different; machines were older and parts not instantly available. You had a job to get a two-penny screw. The Premier did not have the resources that the Co-op had, and the work was also harder. The forewoman at the Premier was Mrs. Thompson. I remember her whispering to me “Doris, I am going to give you a rise, but don't tell the others”. Now I was courting my future husband and so did not mix with the other girls. Neither did I enjoy their company. I was changing and growing up. When I left the Premier to get married the girls bought for my wedding a fine linen table cloth which I have handed over to my Granddaughter. They also bought me a bedspread. After the Premier I went to Raunds, a married woman. Yet despite the difficulties I remember the girls and all the factories and the fun and laughs we had. We stood by each other and told each other our fears and problems and we laughed together at our efforts to put on airs. I also remember the various forewomen that put up with me yet helped me to get on. They were good times and that is why I can still recall their names and after eighty years laugh at our escapades. Doris Roberts 1995. END NOTE Tracing old Rushden factories is a difficult task. The buildings remain but often the firm changes. Mother names the factories as they were called in local talk. To sort out the conflict I studied three Kelly's Directories - those of 1896, 1906 and 1910. It will be noticed that Kelly lists the firm of Robinson in 1896 as being in the High Street and the factory in Roberts Street18 were the same as occupied by West & Childs. In 1906 the factory in Roberts Street is Robinson's. West and Childs have gone. Yet can we be sure that the factory in Roberts Street was the same as that occupied by West and Childs. It could be that Robinson's enlarged the original factory. This appears to be the case on a study of the exterior of the present premises. An old factory stands at the corner of Crabb Street and Park Road, which appears to have been built when Crabb Street was constructed. This became the bottom factory of Knight and Lawrence of Manton Road. Fred Knight's factory in Park Road was at the rear of his house in Little Street. This land ran through to Park Road in which his now greatly enlarged factory now stands. Elland and Howes stood between Manton Road and York Road. Later it extended to front York Road, which became the address. Crabb Street was so named after the owner of the land on which the properties and street were built. 1896. Frederick Knight, Park Road; West & Childs, Roberts Street; Charles Denton, Higham Hill; Fred. Knight jnr. Park Road; Knight & Lawrence, Manton Road; Austin & Bond, Park Street; Ebeneezer Wrightson, Crabb Street; Henry Bull, Harborough Road; John & Charles Robinson, Boot & Shoe Dealers, High Street & Wellingborough & Kettering; Charles Sanders, Park Road, Currier & Leather seller, John Newton, leather merchant, Newton Road; Knight Bros. Newton Road; Bull & Co. Park Road. 1906. Elland & Howes, York Road; Knight & Lawrence, Manton Road; Robinson Bros., Roberts Street; Geo. Selwood, Harborough Road; Chas. Denton, Higham Hill; M. V.Burrows, Manton Road; James Hyde, Glassbrook Road; Ebenezer Wrightson, Crabb Street. 1910. Green & Coe, Newton Road, Wholesale shoe exporters, Shoe Manufacturers. Private Addresses - 1906. Geo. Selwood, Newton Road; Alfred Sergeant, Newton Road; Edward Robinson, 59, Roberts Street; Elizabeth Robinson, 60, Roberts Street. Doris Roberts (nee Watts) 1995 The following footnotes are an attempt to elucidate some of the family relationships, the boot and shoe industries terms and methods, also some historical points. The Memories are not history but memories of past times as seen by one person. Another person may have a different perspective and knowledge - that is up to future historians to puzzle over. 1. In 1812 Sir Humphry Davy did research into the tannic properties of the bark of various trees. Oak bark from Spain was used as the main source lor tannin for the leather The Peninsular War cut off the supply of this bark. Sir Humphry discovered that the bark from Willow, Box and other trees was suitable for use in producing the tannic acid necessary for tanning the hides, It is this discovery that led to the naming of the various leathers. Modern methods and newer materials and also the lowering of men's dress standards these past forty years have generally removed this description from the various leathers. Sir Humphry is generally associated with Cornwall and mining yet 400 persons in 1833 were engaged in shoemaking in Penzance and some 40 in currying. This indicates that one tanner to four shoemakers; this proportion of Currier to shoemaker is also confirmed at Higham Ferrers in 1851. Boot making was the largest employment in Penzance at that period. Cornwall being the great centre of tin and copper mining. His statue stands in front of Penzance Town Hall and his house where he did most of his researches can be seen across the Hayle estuary at Hayle. The above information was taken from an exhibition of his notebook held at Penzance Museum during one visit whilst on holiday. The actual notes on the tannic properties were copied and a copy sent to the CRO. 2. Ecnomeda was invented at Wellingborough, in the 1820's It was a type of glace kid and used for leather gaiters. The market for this type of gaiter employed some 300 workers at Wellingborough It may be that it is from this invention that glace kid was used for light shoes After the Napoleonic Wars there was a swing away from heavy boots to a light boot - the button boot. Improved roads and transport also helped kill off the heavy boot, except in industry which became the ankle boot that we know today. A boot in those earlier times was boot that came to the knee. 3. Grandfather Watts, was born Charles Britain Watts (sometimes spelt Britten) the second son of Edward William Watts who married Fanny Britten. Edward William (reference in Mother's main memories) was the son of John Watts and Mary Tutt. John and Mary had a daughter also Mary born in 1828. Fourteen years later Edward William was bom. John was a shoemaker and listed in 1891 as a ‘rivetter', his father was Thomas Watts; listed as christened at Bedford in 1799 and married in 1802, The Watts’ appear at Lavendon, Bucks, in 1702 from Whaddon. Both Thomas and his son John were Master shoemakers. That is they employed journeymen and apprentices. Grandfather Watts is also listed as a 'riveter'. In 1891 many shoemakers in all the streets round the Co-operative Boot factory in Portland Road are listed as riveters. This process is distinct from the handsewn method of attaching the sole and welt to a shoe. The common boot was riveted. This was a cheaper method than stitching, either by hand or by machine. Riveting is said to have been invented by Thomas Crick of Leicester in the early 1860's. Yet riveting was the method employed by the Romans. It would appear that the riveting machine was invented in the USA. Daniel Sharpe of Rushden claimed to have brought riveting to Rushden; he was bom in a Bedfordshire village near Hitchin. John Watts married at Hitchin in 1826. I have always found it interesting the number of persons in Rushden in the 1880's and 90’s originating in north Bedfordshire villages. The whole matter needs further research. 4Grandma (to my Mother) was Charlotte Goosey who married Charles Matthews. They had five children. Charles died in 1879 of Physythis leaving Charlotte living in poverty in Buckwell End, Wellingborough. Old photographs show these were old wattle and thatched houses in insanitary yards. Charlotte and the children entered the Wellingborough Workhouse; it is believed that it was in there that she met ‘Old’ Bill (William) Denton, who himself had a very sick wife, permanently incarcerated in the Workhouse. William had two daughters by this marriage. Charlotte was the eldest child of Maria Groves Young and William Goosey. When they married in 1841 they lived in the Black Horse Yard, Broad Green. Charlotte was bom in 1843 at St Crispin's Stree, Northampton; all the other children were born at Wellingborough William Goosey was the second son of Edmund Goosey and was apprenticed to shoemaking as a Cordwainer. This was the very skilled work and they made the ‘Turn-shoe’ known today as the ballet shoe (Ref. VCH). In 1861 William is listed as upper shoe machinist living in Jackson's Lane, Wellingborough. It is this small firm that possibly employed Charlotte as forewoman. William Goosey is listed as bom at Brigstock. His father Edmund Goosey was a brickmaker. Before modem brickmaking came about in the 1850's brickmkers would dig clay from pits. They moved about, following banks with clay. The bricks would be baked in turf covered hutments. These can be found in some areas, being called "Fairy rings*. The used clay pit would then be taken over by leather tanners. (The above is from the VCH) 5 Fred Knight had been a Chartist in earlier times in Rushden. At this period there was a campaign in Northampton against the use of child labour for this task. 6 Robinson's of Kettering were advertising sewing machines for leather uppers in an 1868 Edition Teetotal Magazine. 7 Mother fetched the rivets and also the parts for Grandfather. Because of the railway Mother would be unable to use North Street into Rectory Road, but the longer way round by the High Street. It would be a long hard drag from the bottom of Higham Hill up to Cromwell Road. Mum was a small person. 8 Lift dobbing was the making of the heel from small cut pieces of sole leather. There were three types. Halves; this was two shaped pieces: thirds; this was three pieces and fourths; this was four pieces. The whole was stuck together with a paste made from mixing rye flour with hot water. Each part the same thickness to obtain a level and even heel. My Mother, working at home, could earn in a very good week 12/6d. Payment was 2 l/4d a dozen for halves; 2 3/4d for thirds and 3 l/4d for fourths. The pieces of leather were placed on a steel knife shaped to the piece to be cut and fixed upside down on the heavy bench. Then a heavy wooden mallet hit the leather. The leather cut out then dropped into a skip under the bench. The process was very dusty and very noisy with the clouting of the mallet. The finished heels were then pressed at the factory into the correct shape and finish. Each piece of leather had to be the same thickness as the other pieces and the finished heels had to be of a uniform thickness. 9 Selwood's old factory still stands on the left side of Haiborough road up from the Park Road junction. Later another modern flat factory was built further up at the junction with the Pytles This had a classic porch similar to the one on the front of the old Parker factory, later the John White factory in Midland Road, Higham Ferrers. Serwood's new factory has been demolished. The old factory still stands. 10 The story told by my Mother was that Mabel's young man went to Canada first. Mabel was to follow later. The young man failed to get established and sailed back to England and Rushden. Mabel left Rushden to join him not receiving the information. As his boat sailed out of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Mabel's boat sailed in. Mabel stayed in Canada until she raised to fare back to England. Mabel later lived in a house in Portland Road, 11 Paul Cave actually gassed himself in his office. I found this out during a Meeting of Rushden History Society about the time that I took down this memory. This indicates that Memories are not always factual. At the time of taking down these Memories my Mother was listening to the Sunday half-hour of hymns on the BBC. When they sang the hymn 'O God our help in Ages past' Mother remarked that when they had sung this hymn at Paul Cave's funeral service the third verse, 'Hold thou Thy cross before my closing eyes' was omitted because it was a suicide. Also that the coffin stood outside the chapel during the service. But I believe that the Chapel referred to was the small one in the Rushden Cemetery. The story of the Cave's of Rushden is one of great tragedy. 12 Some years earlier at Irchester or Wellingborough a tragic accident bad occurred in one of the ironstone quarries. Was this what effected Sarah Tibbit? 13 Reginald, mother's younger brother, was always into scrapes. On one occasion he was taken by the Police and flogged tor scrumping apples from an orchard. Until taking down this Memory, she had never realized that the orchard in question was Mr. Coe's. The whole story on Reggie is in mother's main memories. 14 The post war years and the now established factory system of regular wages and hours saw some prosperity, especially for the young people. I found all persons of this period rejected the casualisation of the old cottage industry. The factory system de-casualised the boot industry. Bicycles were bought and journeys made into other towns and villages. The development of the cinema meant a Saturday night out to Rushden. A new bus service started up from Raunds to Rushden and on to Wellingborough and Northampton. Locally bus companies such as Walt Dix of Raunds and Seamarks of Higham Ferrers started a service. Later the United Counties Bus Company. 15 The family Chettle were farmers and butchers of Rushden I believe that they lived in the old farmhouse that stands at the far end of Park Road, over the crossing with Harborough Road. 16 The Lightstrung was the bus stop from Wellingborough to Raunds It was on the comer of Church Street and Duck Street. The site has gone with road improvements but to older Raunds people it is still the Lightstrung though the bus stop is further up Church Street now and so called. The name was from the Lightstrung Cycle Company that made the Lightstrung bicycle. The actual site before the Cycle Company had been the first Gas works of Rushden. 17 The factory no longer exists. At the top of the car park in Duck Street is a passageway leading into Fitzwilliam Hill. The site of the Premier may have been located there. Parking in the car park on one occasion my mother said the Premier was at the end of the passage and they used this way to the factory. On the opposite side of Fitzwilliam Hill and on the corner with Moor Road stands the factory of Charles Horrell. This may account why my Mother referred to the Premier doing work for Charles Horrell; larger factories sub-contracted to smaller firms, the common work of a contract. The work would then be done at the larger factory when work fell short, creating in the small factories lower wages and uncertain working hours. Charles Horrell made a high class boots and shoes. The market being the better paid worker and his wife and the middle class. 18 Roberts Street in Wellingborough is named after the Rev. Mr. Roberts Vicar at Wellingborough during the C19th. He was a much-loved figure. When many Workhouses listed children under pauper, idiot or illegitimate, he, Mr. Roberts in 1851 listed them at Wellingborough Workhouse as Scholars. He was born at Liverpool. One wonders whether it was his influence that caused Great grandmother to change from Independent to Church of England. She had all her children baptized in that Church in their early years; this was after they came out of the Workhouse.

|

||||||||||||||