|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| KB (Keep Believing) by John White 1969, transcribed and presented by Kay Collins |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

John White - Autobiography

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

KB - (Keep Believing) - The John White Story

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

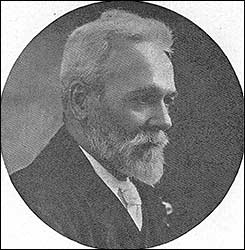

I was the youngest, of nine brothers and sisters and we came from a long line of shoe makers, or cordwainers to use the correct and more colourful term. The first John White, cordwainer, I can trace was baptised in St Mary's Church, Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire, in 1767. Our world was a rigidly religious one; our faith, Strict and Particular Calvinistic Baptist. I don't remember much of my early childhood with the family - my sisters took care of me by turns until they married. They were much older. So it is my father I remember most. He divided our little village into three sections of humanity for us: The strong-minded, strictly religious folk like us; those not so religious, but pretty hard-working and careful, who in time became foremen or managers and built their own houses; and below them the drunken and lazy layabouts. Times were not hard in those days in the shoe world. The pubs were open all day and a great deal of drinking went on. Some of the men worked when they liked and I can remember how they decided when. Discipline was poor when men first went into the factories and often those of the drinking element would meet around the cross at Irthlingborough of a Monday morning and debate whether or not they would go to work that day or have another day on the booze. They had a simple method whereby they resolved the matter. They would throw a brick into the air. If it stopped up, they went to work; if it came clown that would settle it for them! As a little boy, I spent a great deal of time watching shoe makers at work - my father wouldn't allow much else - so I always took it for granted that I'd enter the trade myself To keep me out of mischief, my father used to have me read to him. It wasn't that he couldn't read; he devoured a great deal of religious literature - tracts, the Gospel, and such publications as The Standard and The Banner. I used to sit in the evenings and read to him while he made shoes. Robinson Crusoe, Uncle Tom's Cabin, The Swiss Family Robinson - books which pleased him and delighted me. I have always loved books and even those early adventure tales made me want to be my own boss one day. This experience created in me a great love of literature which has remained with me all my life, encouraging me to build up a fine library containing most of the classics. From my earliest years I would sit and read to him for hours at a time while he did his work. Very attractive work it was too, calling for a considerable amount of skill. The colouring and the decoration of the shoes was much more carefully done than it is today. There were invariably beautiful colours on the soles, which would come off in an hour in the wet, but nevertheless that's how they had to be done. Father always had a Bible and a hymn book on the seat from which he would read extracts during the day. And every morning, before we had finished breakfast, he would get up and go into our little parlour and spend half an hour in prayer. That's the sort of man he was: religion was his life. Death meant nothing to him at all. He would just go 'from this room into the next'. I went to the village school at a very early age and I think I acquitted myself well. I can recall that all through school, I was near the top of my class. I think I was above the average, especially in arithmetic and reading. My first recorded business deal came at the age of eight when I started to breed rabbits, I was absolutely innocent, with no knowledge of the sex life of animals, but knew that if you put a Flemish Giant to a Belgian Hare you would have young ones. I heard that a woman in Irthlingborough owned a Flemish Giant. I had a female Belgian Hare, so I put her in a sack and took her to the woman, who lived in the most squalid part of the village. The woman came to the door. She was the most disreputable person I had seen at that age. She just said ‘put it in there', indicating a wooden box in which her own rabbit was kept. After about ten minutes the woman came out and said 'Has she had enough?' I said gravely, 'Let it stay a little longer', without understanding what was going on inside. Eventually, the woman came out again and I took my Belgian Hare home. In a few weeks' time, there was a lively litter of rabbits. It was my first financial deal, as I sold them triumphantly for sixpence each. We had a fairly comfortable existence. In those days, men like my father toiled at home, usually working until late at night and doing gardening in the middle of the day. But my father didn't follow the normal pattern. He went to chapel at every opportunity - and he liked me with him. He would not let me mix with the rougher elements in the village and so often in the chapels I would be the only little boy among perhaps 100 elderly or middle-aged people. It was a rather forbidding life for a boy but I only ran away from it once. Close to the village there was a very pleasant river, where I used to bathe until a little friend was drowned, then my father wouldn't let me go any more. On the banks of this river, about a mile from Irthlingborough, was an orchard with a lot of crab apple trees. The kids used to go their every Sunday evening - the boys who didn't go to chapel. One evening I stole away and went with them. My conscience pricked me long before the service was over and I ran all the way back to mix with the crowd coming out of chapel. It didn't work; one of my sisters gave me away and I can still feel the hiding I received!

I left school at twelve, against my father's wish; he wanted me to carry on longer, but I was eager to go into the trade. I'd seen so much of it all through my childhood that I was soaked in it. Shoe-making was a rewarding trade to enter in the early nineties. If men liked to work, they could earn very good money. I know someone who worked by himself in a tiny shop. He used to earn £5 a week receiving sixpence a pair for making little riveted shoes. There weren't stitched shoes in those days and all the work was done outside except for the clickers in the factory. The clickers were the workers who cut the upper, traditionally the most skilled men in the trade. There would perhaps be a sole press cutting the soles but all the other work would he given out. I joined the trade just at the time they were starting to put machinery in to deal with foreign competition. Although the factory I joined had scarcely any machinery at all in my first months, they soon had to become mechanised and the trade developed swiftly into a machine industry. Those who used to work outside went into the factories and had to keep time and accept more discipline. This caused some trouble and I can recall a big local strike, called the '7-16 edge', in 1895. I remember two 'scabs' went to work in the factory. Most of the 3,000 people from the village surrounded the plant and hooted and jeered them when they left. Of course, I joined the crowd; I didn't know why they were there, but I jeered anyhow. The men didn't go in any more and the strike was soon settled. When I began work, I received 18 pence a week, with the promise of another threepence in six months if I was any good. I worked at inserting eyelets, and would put in about two gross pairs a day. These days, a girl in a factory could do 2,000 pairs a day, as easy as pie. Then, you punched a little hole and the boy next to you put the eyelet in and clinched it. Two boys together - that's all there was for an eyeletting machine. I only worked at this first factory for a little time and they didn't object to me looking for another job. I tried another factory where I did a job a little more skilled. Later, I moved to a third and learned a bit more about the job; then at the age of 16, I joined a brother-in-law in a family firm. All this time, I gave my father my wages, and he allowed me to keep something. I don't remember how much it was but I always took great care of it! So far as equipment went, my brother-in-law's establishment was the worst factory of the lot. They hadn't got any machinery, apart from one for cutting the soles. At that time, scarcely any factories in the area had got a stitch machine and the job of stitching the sole to the upper was usually done by an outside 'trade sewer'. You would take a job one day to a trade sewer, leave it, and collect it the following day when you left another consignment. There were only two factories in our area with a stitching machine. Being the youngest boy on the staff, I was very often told to drive the pony and trap to Rushden to take shoes to be stitched. We had a little pony as black as ink called Satan, and I would drive Satan to Rushden with the shoes. You couldn't make him do anything but walk to Rushden; but turn his face round, and coming back he would race all the way! We did that journey hundreds of times. My brother-in-law was always short of money. So I would be in there until 12 o'clock at night, dressing and packing to get them away early in the morning so that he would get his cheque back as quickly as possible. When the cheque came I, being the youngest of the staff, had to walk four miles to Wellingborough to put it in the bank as soon as it opened. Scores of times I walked to Wellingborough with those cheques. Of course, there could be only one end to such an existence. I could see there were no prospects and, although they didn't like it, I left. In 1902, I joined John Shortland - at what was then called the Express Works. I went as a clicker, because I'd learned something about it. There were probably about eight clickers then, but the business grew rapidly because he soon had every available machine in the factory. John Shortland was a progressive man, very up-to-date; I stayed there about eleven years. Please don't think I am boasting, but I knew that I had talent, more talent than the average man in the factory. We had cutting sheets each covering say, 500 feet of leather. You had to write down how much you had cut out of it; how many feet you had saved or what you had lost. Mine always made an enormous gain. One day John Shortland came into the room, went to the foreman, and showed him my stock sheets. He said: 'You mustn't let this pass; you must give this man a four-bob rise'. Four shillings was a lot of money in those days. I was 21 and earning 22/- a week. There hadn't been a clicking press in the area until John Shortland acquired one. This new machine chopped uppers replacing the hand process. Because of my ability, they gave me the job of working it. Where we cut about 60 pairs a day by hand we cut 120 pairs by the press; but very arduous work it was because the press then had not been perfected. It had a kind of a buffer you pulled round to touch the trigger and chop the leather. Often, it would stick and come down with a sickening thud, then you had to take the machine to pieces before you could get started again. You were still, however, expected to do the same amount of work. They soon improved upon the press, of course, and when I left Shortland they had a long row of presses. But, it was still factory work and I did not really like it. An elderly workmate said to me about this time: 'John, for forty or fifty years I've stood in front of a frosted window. I'm going to see that none of my children do that'. (All the factory windows were frosted then). And I said to myself, 'Neither am I'. From then on I made determined efforts to find some way to become my own boss; it was now, more than ever, my life's ambition. I would get away from temperamental and often cruel foremen. It was when the machine age came that the trouble started: unemployment, low wages and very different conditions to the easy-going life we had known before. I well recall at this time the great Raunds strike of 1905. Raunds men were making army boots on very low pay, and they struck for higher wages. This went on for a long time, and there was much bitter feeling and some window smashing. Then a chap named Jimmy Gribble became their leader and he soon put some life into the strike. He led the men to the Houses of Parliament in a spectacular march to London. One man did it with only one leg. They went to the Commons and, after some difficulty, got a hearing. Then was established what is known as the 'Red Book', which raised the army prices considerably above what they were getting and made lower wages an offence. All the rises since then have been based on that one basic figure.

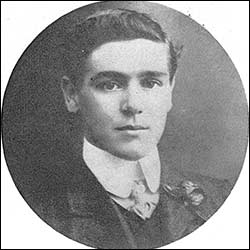

In the pool, the minister would take his position and wait for the participants in the ceremony, the men coming from one vestry and the girls from another, clad in very light clothing for the purpose. The ceremony of baptism is the most important of all in the Baptist Church, and until they had undergone this particular rite, they would not be able to take part in the ordinance of the Lord's Supper. As they walked towards the minister, he would put one hand behind their back and one on their breast, and completely immerse them in the water as, we understand, was done to Jesus in Jordan. Meantime, as each one was immersed the congregation, which was always a very large one, would sing 'Praise Ye the Lord, Hallelujah, Hallelujah. Praise Ye Lord'. When my mother's brother, who was a fervent believer in baptism, rose out of the water, he shouted: 'Repeat it! Repeat it!' at the top of his voice. He was most earnest in his faith, but he still managed to marry three times, each succeeding wife more prosperous than the one who went before - but that is another story! Too strict for me it was, and one night I went with a friend to a Wesleyan Chapel. My father got to hear about it and called me before him next morning. He said: 'You went to Wesley last night?' I said 'Yes'. He told me gravely: 'Well, if you'll promise me you'll always go to a place of worship on Sunday I'll forgive you'. So I started to go to Wesleyan Chapels and began a round of those in the district. One Christmas Eve, I found myself in the Park Road Chapel at Rushden with the result that I got an invitation to a social evening. There, in 1906, I met the principal singer in the choir, a very pretty girl of 16. Four years later I married Nancy Darnell. I don't know about love at first sight; it was more a mutual understanding and liking for the same sort of things, specially music and singing. That's the real truth: the same sort of things. We both dressed ourselves very nicely, and before we had been courting long we were saving together, with one account in the Post Office. We went everywhere happily together, cycling around the countryside, and took great care of our money. We grew to like each other very much. With all my new happiness, I still found it hard to get away from my own rigid life. Hers was a very different home. Her father was a manager in a factory and was rather fond of life. He liked a day's fishing with his pals, enjoyed a game of cards, and the occasional whisky. He was a very intelligent man, and though he had a religious background, did not take it too seriously. Her home life was so different and light-hearted compared with my dull and stern one. I had never known a mother and now I realised just what I had missed. I even started to study farming - I took the Smallholder and Farming News and thought I'd become a dairy farmer. In 1911 we were married. She was a beautiful home-maker. Everything was wonderful. I will never forget the first day I went home to tea from my work: the wonderful difference between a wife and the housekeepers we had been used to for so many years. We had saved exactly £100. So we rented a house and furnished it beautifully for that money. But not on the 'never-never'. We bought nothing on credit. Village life was dull and my wife liked to get back to her parents and her sister in Rushden. She used to cycle to Rushden pretty well every afternoon and get back in time to get my tea. There was nothing much doing in the village - although they filmed The Battle of Waterloo there in 1912 and had a skating rink which flopped after a few months. The film producer married a local girl, a friend of mine married the skating instructress, and the man who was instructor married the Lord of the Manor's daughter. In 1912, when we had been married a year, Charles Horrell of Rushden advertised for clickers. It was our opportunity to settle in Rushden. I knew Horrells so I got on my cycle at 8 o'clock in the morning and went to Charles Horrell's office. The keenest little man in the business, and the most successful, received me very courteously. He'd been a clicker himself before he set up in business so he knew the qualifications required for the job. Horrell put me through a long examination. Then he said: 'Well, how much money do you want?' I said: '32 shillings a week.' He said: 'Oh no, no, no. We don't pay that here, 28 bob's the maximum.' I said: 'Well, that's what I want if I come, 32 shillings'. Horrell then said: 'Well, I'll make a bargain with you. If you'll come for a week on trial I'll give you your 32 shillings'. So I went on trial and he gave me more than I'd asked for. Providence had favoured us again. We had a very beautiful house in Rushden. My home was everything to me, it was to both of us - everything. I got a piece of ground in Rushden, and I grew everything that we needed in the house. It cost us scarcely anything to live, scarcely anything. I was pretty good with a hammer and a saw and could make things like trellis work and garden seats but I don't think I ever washed up a cup. I was no good in the house at all. We were deliriously happy. She pinned up a line of poetry on a little bit of velvet which hung on the shelf on the fireplace: 'Hast thou ever been in Arcady?' That was there for three years, and it was Arcady indeed. I was getting on well at Horrell's, and now didn't feel so keen about getting out of the trade. Horrell appreciated my ability and rewarded me well. We had to work fairly long hours, but the pay was good and I had my first income tax demand there. My first tax demand, and it was for 4d. I said to my wife: 'Surely they won't bother about that', so I didn't send it. But in a few weeks' time I got an irate letter saying that if I didn't pay dire action would follow. I sent them four penny stamps, only to get back an even more threatening letter saying that stamps weren't legal tender and that if I didn't send the money action would be taken. Believe it or not, that tax inspector became one of my greatest friends. Then came 1914 and the war. We had had about two years' real happiness. On the first of September, 1915, my first little girl was born, and on the 15th of that month I went to the barracks to enlist. They said, 'You're engaged in the shoe trade, you'll have to go back till we call you'. They wanted shoes more than they did men. It was a long time before the shoe people were called up again. Then I went off with a carriage load of men around my own age, who smoked, laughed and sang all the way to the barracks. I was kept overnight. Then the doctors called me in, asked me a few questions, and said they were going to put me in a lower category and send me back home again. I went back to work long hours to keep the forces supplied. In October 1917 I was called up again, but was finally rejected. The doctors said: 'You do too much smoking, give it up'. I hardly smoked at all, but they attributed to smoking the fact that my heart was racing. My heart is as good as anybody's but any strain and it races like the dickens. That's what it was doing when I was examined. So I went back to the factory again, for the rest of the war - to long-hours but high wages. Pay had gone up from an average 28 shillings to about £7 a week. That was a lot of money then, and I thought here was an opportunity to do something for myself. At the end of the war in 1918 we debated, myself and the wife, and decided to 'have a go'. We had saved another £100, but I couldn't find anywhere to start in, no shop, no room.

I began by buying enough upper leather to produce 500 pairs of uppers, leaving the rest of the money for some sole leather when I could get it. I also wanted a sole press to cut the soles and placed an order for a very nice one. But unfortunately I had overlooked the fact that I would need a machinery licence and I just couldn't obtain one. This was rather a serious situation. I produced the 500 pairs of uppers, hoping that something would be done about the press, but weeks went by and there was no news about the licence. We had invested all our capital and Christmas 1918 was a very anxious time indeed. One night about Christmas time I turned out my gaslight in the shop and went home to supper. After supper I went into our little garden. It was a beautiful, clear, night. I wasn't depressed - I had no anxiety about being out of work and felt sure my old boss would be only too glad for me to go back. But my life's ambition seemed to be falling apart, and I feared I couldn't get any further. Sitting there, under the stars and thinking, I remembered Tennyson's quotation: 'God is a spirit, speak to Him thou for He hears, and spirit with spirit can meet, closer is He than breathing, and nearer than hands and feet'. And at that very moment, an inspiration struck me: to do something which had never been done before in the trade to my knowledge. I resolved that Christmas in my garden to try to sell those uppers to another manufacturer. With the money I would buy more leather, and so carry on until I got my sole press. Well, I went to bed with that on my mind. Next morning, I dressed early - I can always remember because it was a day of brilliant sunlight - got on my bike, and I thought . . . 'Well who shall I go to see first?' I knew one well-established manufacturer who was a very eminent churchman, a teetotaller, a non-smoker and everything that was good. I thought that surely he was the man I should go to see. I knocked on his office door and he quite courteously asked me to sit down. I told him that I wanted to sell some uppers, and showed him a pair. He said: 'Well, these are all right, where did you get them?' I said that I had made them myself. He hesitated; then I saw him get out a little pad. He asked me a series of questions. 'How much did the leather cost you for the outsides?' 'How much for the linings?' 'How much did it cost to close them?' (that meant a woman's work). I told him my costs and said I had cut the uppers myself. I noticed him doing a little sum on his pad, and then he offered me ninepence a pair less than they had cost me. I don't quite know how I came out of that office; I remember saying 'thank you', closing the door behind me, and saying to myself: 'John, you'll be a hell of a while making a fortune at that rate.' I wasn't dismayed, however, and went to another manufacturer of the same ilk. I showed the uppers to him and he said: 'Yes, yes, they're all right, how much do you want for thern'. I told him and he offered me exactly half what they had cost. I thought: 'We’re getting along fine!' I got on my bike again and went to a chap of my own age, who had been in business through the war and had clone well for himself. He told me frankly: 'No. I don't want them. The war's over. Its going to be a tough fight. You sell them for what you can get for them and get back to your bench'. I thought, 'Not likely'. But he had been quite sure about it, and his advice was well intended. Sad to say, it was going to be a fight - and he was one of the first to go under. Afterwards, he worked for me for 30 years. Now he's my oldest pensioner. Anyway to finish the story, he ended by saying: 'I'll tell you what to do. Go up to see Jimmy Hyde (another manufacturer in the town) he'll buy them'. Still not depressed, I got on my bike to go and see Mr Hyde, known affectionately as Jimmy. He wasn't there and I waited. Mr Hyde was lunching that day with a customer, followed by drinks at the Conservative Club. So when he did come back he was in quite a cheerful mood. Eyes sparkling, he made exactly the remark as the first man I had shown them to: "Ah, these are all right; where did you get them?' I told him I made them myself. He said, 'How many have you got?' I said 1,000 pairs and he asked what price I wanted. I was going to ask him 5/6 but then I got a brain wave and asked 5/9d. Mr Hyde thought for a moment, then said: 'All right, send them in. Pick your money up Saturday, my daughter will pay you'. I got on my bike and Mercury's winged heels were nothing to what mine were as I cycled back to my little shop. I remember putting my finger into my waistcoat pocket where I kept a little silver cross and thought that if this wasn't providence I did not know what could be. I recruited at once a dozen little old ladies who had their own machines, and used to close outdoors, and I found a couple of clickers who didn't mind doing a bit of clicking in their own homes. I found boards for them to cut on and I delivered those 1,000 pairs on the Saturday, The daughter who paid me was then about 18, and very attractive. She married a clicker who worked for me for 44 years. Hydes kept buying those uppers in 1919 and I thought that if they were useful to them, why not other people? So I approached one or two other manufacturers, and began engaging no end of men outside to cut the uppers. I started to do quite well, for the simple reason that I knew what I was doing, knew how to cost, and how to charge for them.

Now, I was able to make boots and shoes up to the finishing stage, and I had a brother-in-law in the town who finished and despatched them. Then I think it was the end of 1919 I thought it was time to approach the regular shoe buyers, so one morning my wife and I went by train to London. I had six samples in a little papier mache case. We went up to Lilley & Skinner, the biggest people in the trade at that time. The slump was on and the buyer said: 'Do you mean to say you're going to start shoe manufacturing?' I said 'That's my idea'. He said grimly: 'You deserve a Victoria Cross. Come with me.' And he took me through into his stock-room where there were thousands of pairs of shoes they couldn't sell. In the end, he shook hands with me and said: 'My lad, you come in about six years' time and I'll have a look at your samples'. My wife was waiting outside, and we still had a bit of spirit left. We took a bus to Shoreditch to Darnell & Son, the dominant factors at the time. I took my seat with about six other seasoned travellers. My turn came to show my samples, and a chap came and looked through them, picking them up, putting them down, one after another. I thought it didn't look very promising. But when he came to the last one, he took it out of the room. He came back later with a man who was the senior buyer. That buyer's name was Andrew Galloway Thompson, and in my view he was the finest buyer this country has known. He looked at the boots and said: 'Will these boots come in like this if we give you an order?' I said, 'Of course they will, I made them myself. He said slowly: 'I'm going to give you an order for 72 pairs. If they're all right, we'll give you a big order'. The bus couldn't get back to St. Pancras quickly enough for us to get home to Rushden and go to work. I cut those uppers myself, beginning in the evening of that day. I gave a dozen pairs out to each of six women to close. Then, when the uppers were done, I gave them out to six men to make. My brother-in-law finished them and I delivered the whole job in something over a week. I engaged an old man named Jarvis to take the shoes to the railway station on his pony and trap. But first I had to get them to Jarvis at the bottom of a steep hill. I remember manhandling them all on to a hand barrow - the six dozen pairs of boots made a heavy load - and pondering whether to push or pull it. Finally, I decided to take the weight behind me, but as I got further down the hill the load got too heavy for me. I was propelled faster and faster until I finished in a heap beneath the wheels of the trap waiting for me! I wasn't hurt, but onlookers said they had been worried for me. Anyway, that's how the first consignment of John White footwear was delivered. Darnells got their order by 10 a.m. the following day and, within an hour or so, I received a telegram asking how many I could do. I cannot recall the fabulous figure I quoted from the top of my head in reply, but it resulted in a big order, the first of millions of pairs of shoes which I sold to Darnells. By the end of 1919 I had a staff of four people including myself. The fourth was a nephew who had been a prisoner-of-war in Germany. The shop was never big enough for us all, and the worst feature was the old hymn-singing Salvation Army chap who cut the soles. Then he failed to turn up one day and we learned that he had broken down and gone on the booze. So I had to work the press myself for quite a time until he reformed and rejoined the Salvation Army in a penitent state.

In the finishing department, you have to have dust extractors. There weren't any, just sacks tied on the ends of the machines. So consequently every corner was thick with dust and dirt. My dear wife came in, engaged a whole body of women, and cleaned that place from top to bottom; made it spotless. I then installed a dust-extracting plant. Outside was an old 20 h.p. gas engine which wouldn't start on cold mornings. So I kicked that out and put an electric motor in straight away. Now I had a full finishing plant, so I could make my own shoes from beginning to end for the first time. I was only about two years in this place, but I turned out 2,000 pairs a week. I engaged scores of employees, but there were also a lot of men making shoes outside. It was a long time before I had machinery to make the shoes. Things had got bad then; a slump was developing. My little shop was only 30 yards from the labour exchange and there was a constant queue of men casting longing eyes at my busy throng of workers. I packed that shop so full of men that when the shoes were made I had to pack them outside in the street. On the top floor I put clickers, on the middle floor sewers and stitchers, to stitch the soles. In one of the big rooms I had a team making shoes by hand. On the ground floor was the finishing plant. So it was a really compact little factory. I packed it so full that some of the workers trembled when buses went by as the vibration made the building sway. It was during this period that the taxation people discovered my presence again. I was clearly now worth more than a fourpenny demand to them! I received a summons to see the Inspector of Taxes at Wellingborough. My wife went with me and she walked up and down outside the building during my interview. The tax man was very kind really. After a long chat about the weather and the shoe business, he said: 'You appear to be doing very well for yourself, don't, you!' I replied: 'Perhaps - but not as well as I'd like to' - or words to that effect. The inspector then asked: 'You've got a balance sheet haven't you!' I said I hadn't - I had been too busy. So he told me to have a balance sheet drawn up - pronto. So I saw an accountant and produced my first balance sheet. The first tax demand was not very great - but I have been well inside their net ever since.

Within months I extended the Newton Road factory. Three more extensions followed, in 1925, 1927, and 1928. Naturally the progress I was making, with full employment, overtime and everything, caused much curiosity. There was only one reason for it according to other manufacturers: I was giving them away. But in fact I was making as much money in half a year as some of them would in a lifetime. My reason? I got my costings right. I did them myself. Every single one. I stamped every costing. Each job had to carry a profit and a good profit for the year in question. By 1925, the output was growing at such a rate I could no longer make enough shoes by hand. So I put in what we call consolidated lasters. I installed two for a start, but I had soon to increase the number because output was still growing. The dear old men who had worked for me for so long were very worried and afraid they would lose their jobs. They called a meeting in one of the Rushden pubs and appointed a deputation to beg me not to put in any more machines. Of course, I had to have more machinery to meet the demand for shoes, but I found every single one of them a job. Many came inside the factory to work with me, and most finished their working lives with me.

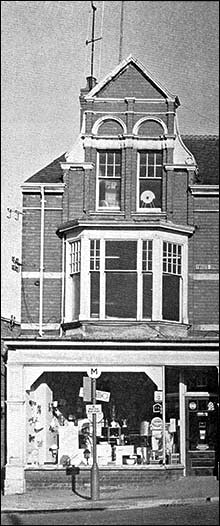

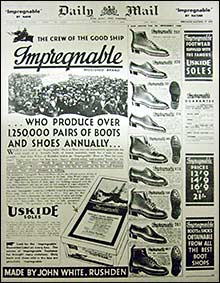

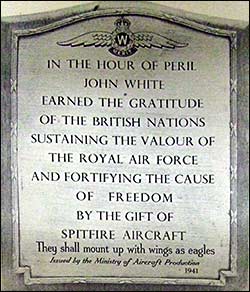

Things were difficult in the trade then and I wanted to get away from cut-price shoes, I wanted to have something offer which I knew was good, which would interest people, and build up a reputation for myself. So I decided to launch my own brand of shoes. About that time, hearty reader that I was, I became fascinated by a book written by Harold Begbie. It was called Broken Earthenware, and went to my heart. It was the story of people in difficulties, and how they kept heart. The two central characters were young Salvationists who were forced to live apart. Always when they wrote to each other, they headed their letters with the capitals 'KB'. So when I introduced my first range of shoes, the first catalogue number was KB too. I told nobody what 'KB' meant until 30 years later. It stood for 'Keep Believing', and that's my motto. You can still find KB in the John White catalogue today. By 1930, I was starting to feel competition very keenly. It was clearly going to be hard to maintain my position and to employ all the hundreds of people I had. It was then that I took a bold step. I was entirely my own boss, so I decided to go in for national press advertising. No shoe manufacturer had ever dared it before. The Daily Mail front page then cost, I think, £1,200. That was a fortune to spend on advertising in those days, and a very big step for a man on his own without any other capital, except what I had won for myself. But prices had got so low and the manufacturers who were trying to meet them were making a class of goods that I didn't think was worthy of the skilled work of the people employed. I decided to introduce a brand of my own, a brand that nobody could undercut and to sell them at a fair and reasonable price. They were, called 'Impregnable' boots and they were my first branded footwear. I launched them with a Daily Mail front-page promotion - then the world's most expensive shop window.

In 1930, I made 1,250,000 pairs in the year, compared with only 100,000 in 1921. Nobody else had the courage to advertise like that, yet by 1931 I had completed my first really big extension as a direct result of that single advertisement. I went on in the thirties to build up advertising to £80,000 a year, which was a lot for a company the size of mine. Lloyds of London carried out the drawing up of the advertisements. We were later making rather more than £7,000 a week profit. Half that was made in the factory, and the other half-was discount received on purchases. That was a counting house profit, for being quick off the mark. I didn't have to wait until Christmas to know whether I'd made a profit; I knew exactly what I was making every week. By that time I was dealing with nearly everyone in the industry. When Sir Isaac Wolfson took over G.U.S. I sold him his first batch of shoes. By 1937 I was supplying him with nearly 300,000 pairs a year. Soon after we went public we began making almost two million pairs a year. Then Carreras introduced a cigarette coupon scheme for shoes. I was approached to make them and it was certainly a tremendous job. We floated a little company, John White and two smaller manufacturers. I don't know how many millions we made, but I made a million pairs myself for them. This went on for two years until Carreras got tired of handling them. They weren't anything like the 'Impregnable' shoes, of course, but some retailers were angry about the coupon competition and said they would not buy any more from John White, but in time they bought more than ever. I was never all that enthusiastic about the coupon shoes but it was business and it helped to keep the wheels turning. Things were bad in the 'thirties and nobody in the area prospered as we did. One after another old-established people went out of business. Old Mr Hyde, who bought my first uppers, packed up. Jobs were scarce, and if I advertised for a man I would have 300 or 400 applicants. The factory was filled until it reached the 2,000 mark. I saw most applicants for jobs myself. Practically every man and woman in the factory knew me personally. They knew my origins and my earlier life and respected me for it. Everyone knew me as Jack. I can't remember sacking anybody. Those who left usually came back within a fortnight. We had wonderful social occasions and staff outings. If a woman in the town wanted credit from a dress shop they'd ask for whom she worked. If she said 'Jack White' she had all the credit she wanted. That's an absolute fact. My people had constant work, never lost a minute; they had high wages and security. By this time, my boots and shoes were being sold all over the country. There were, by 1936, competitive branded shoes, so in order to sell something that was above the level of the low-priced stuff being made, I introduced another brand of lighter and cheaper footwear. I got permission from the National Gallery to use Turner's 'Fighting Temeraire' as a label. When we launched 'Temeraire' shoes, we had a big stand at the Agricultural Hall at Islington to promote a range of shoes at 10/9 and boots at 12/9. They went like wildfire. 'Temeraires' used up all the production capacity we had left over after the coupon shoes and we couldn't get enough transport to take them to London quickly enough. Then, of course, they were copied widely but it didn't seem to make much difference.

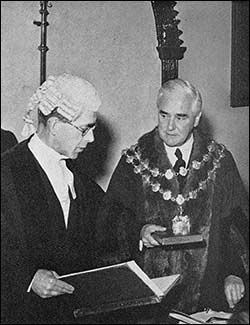

The offices were opened by the Mayor and I remember the accountant telling me that when he joined there were only five people in the offices. Now there were fifty. We put a plaque in the hall, designed by Professor (later Sir Albert) Richardson: 'Let the beauty of the Lord Our God be upon us, establish thou the work of our hands upon us, Yea Lord, the work of our hands, establish Thou it'. That's from the Psalms and it's a favourite of mine. During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) we supplied boots to both sides. I know that we took an order for 100,000 pairs from the Franco side. They paid before delivery and were delighted with the job. Then came another order, through a London agency, for a further 100,000 pairs. These, we learned later, were destined for the Republican troops, but we never knew whether they reached them. It was not to be the last odd experience of this nature for John White. In those last pre-war years, we were really going ahead. I had extra managers everywhere, good ones too, I made sure of that. But two of them thought: 'If he can make money like that, why can't we?' So my two most important managers left. There was an empty factory in the town and they started what they called the Legion Boot Company. They carried on for about a year. In the second year they were in trouble and failed badly. I'd been to London one day, when I got out of the train, I met one of these chaps shaking with emotion. He was going to a meeting of creditors and thought he would lose his house. I said: 'Now look here, don't think any more about it. Go and get this over and come back and see me'. They came back to work with me until they died, both of them. Around 1937, Marks & Spencer were selling vast quantities of 5/- shoes. The smaller retailer was feeling the effect of this very badly as they had nothing to compare with that price, or anything near to it. So I set out to provide something for the merchants to deal with this very fierce competition. To give an idea how prices were at that particular time, and how narrow was the margin of profit, I produced a shoe which I sold at 3/10½d. a pair, less 6¼% discount. The upper leather at that particular time cost 3¼d. a foot. I produced a youth's outside complete upper for 6¼d., a boy's for 4½d. Yet each cutting sheet showed me a gain of 3/1d., even at those ridiculously low prices. What they would be today I shudder to guess! With those shoes the little retailer was able to compete (if he wished to) with the 5/- shoes sold by M. & S. He could even under-cut them. In order to try to beat competition of that type some manufacturers attacked wage rates. They paid daywork wages and expected a lot of work for the money they paid. I pioneered piecework: payment by results. I believed all the way through in paying by results. I tried the other system for a while but didn't like it, so it was dropped. I had no union trouble as a result.

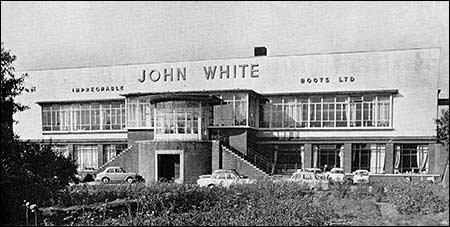

Just before the Second World War, I built he most beautiful factory in the shoe trade, at Lime Street, Rushden. Again, its design was the work of Professor Richardson, and naturally attracted great attention. Many notable people came to see that factory in the years that followed, including the Duchess of Gloucester, Lord Woolton and Mr Hugh Gaitskell. For a time we floodlit the building in our pride; then with the war we had to turn off the electricity because the illumination could be seen by an aircraft 60 miles away.

By 1941 I had nine factories, a staff of nearly 2,000, and we were producing three million pairs of boots and shoes a year. We concentrated on making shoes for the services and produced in all more than eight million pairs - one ninth of the footwear supplied to the British Forces. The authorities this time were very strict. They checked profits carefully and always had cost accountants examining the books. They would get a stack of my cutting sheets - probably 1,000 sheets - showing tremendous profits. Perhaps the next manufacturer was showing none at all, and they used to take the sheets to him and say: 'Why can John White do this and you can't?' That made for some bad feeling; but it was just that they hadn't got the knack of watching costs which I always possessed. We made immense profits, but were not allowed to keep them. This didn't cause me any concern: I was proud to think that even producing totally different footwear to the civilian stuff I was used to I could still beat everybody else. We made a remarkable variety of service footwear including the Army ankle boot; a knee boot for drivers; jungle boot; the special boots made for commandos and the R.A.F.; a flying boot; canvas boots for the Royal Navy and the nursing services. Few firms in our field anywhere in the world could have helped the war effort in so many ways. Our products were also a good advertisement. Long after the war, ex-servicemen used to send for our products because they remembered that their wartime boots had the name John White stamped inside them. Many men, I know, are still wearing their issue footwear - they were such wonderful boots.

We also made 100,000 or so pairs of shoes for the Red Cross in Switzerland. I called on them there after the spending the only two nights away from my wife in 58 years of marriage. After the war, a boot you paid 12/9 for in 1917 had to sell at 54/-. I soon decided that the factors were not promoting my shoes as well as they should in terms of the advertising I was doing. So I decided to break away from them, to leave the wholesaler behind and sell direct to the retailer. How difficult it was, however, to break away from Darnells! They had been such good friends all through the years. But the buyer for the 24 years I had traded with them had retired. A new man was there, with whose methods I did not agree. Slowly, the great empire was fading away. I didn't mind leaving the other factors because they had not done what I thought, they should do in support of our advertising - but Darnells in the past always had. I was very grieved to have to tell Darnells of my change in policy. I did the job of sacking them myself, without telling the other directors. I was a bit of an autocrat! The new buyer at Darnells took it rather badly, and sent me after 24 years’ association a rather bitter picture. Our official number at Darnells was 57. He had a picture painted of a funeral, with an open grave and a coffin being lowered, into it. On the coffin was number 57, the John White number. At the head of the grave was the minister in his surplice and at the other end in (silk hat and black) was myself watching my number being buried, with the staff of the company mourning all around. But, sad to say, it was their funeral, not mine. This great company, in not so very many years, disappeared completely. I got great support from the retailers and profits mounted rapidly after 1945. From about £50,000 up to £200,000, then to £300,000 and £400,000. My personal capital rose to £1,500,000. I maintained the prices and we had the intermediate profits which the factors had been getting. It was a good move on my part and it established the business more firmly than ever. We hadn't got the worry of competition. Our branded lines were very reasonably priced and nationally known. The next major step was in 1951. I made a tour of all North American centres to which we were exporting. I went to New York with my wife, and saw Eatons of Toronto who were the biggest importers of John White shoes. I went to Miami, then flew to Jamaica. Later we went back to Chicago where I saw many shoe people and went into American shoe factories and saw their methods. I was very impressed and brought some of their methods back with me. A rather amusing thing happened in Chicago. I was leaving to catch the night train to Toronto when a doorman circulated a report that I was the Premier of Canada. When I got outside, he'd collected a crowd to see me off to Toronto. I took a cab, and at the station there was another crowd! After Toronto we went to Montreal, Calgary and Vancouver. We stayed in Vancouver about a week, then went to Boston where I met a man named Jack Atkinson who had been chasing me to ask for representation in America. We did some negotiating, then I went on to New York, he followed. He still hadn't been given the representation. He hadn't even seen my samples and knew John White by reputation alone. He tracked me to our bedroom in the Waldorf Astoria Hotel where he saw my samples for the first time. He was so enthusiastic that I made him American representative on the spot. Soon, we were sending four hundred thousand pairs a year to America, 90 per cent of all the shoes exported from this country.

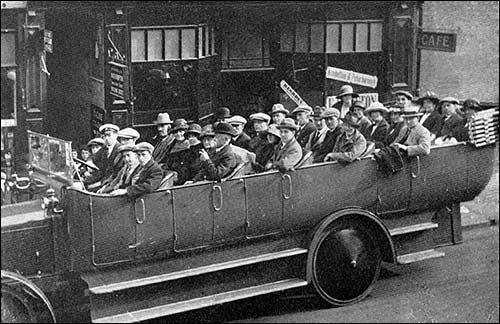

When I got back home, the Festival of Britain was in full swing so I took the whole of my employees to London - 2,600 people in 86 buses. We couldn't get all the buses into the Festival so we got off further up the Thames and cruised down to the South Bank in a fleet of barges. I got my staff the best seats in all the theatres in London. I forget which theatre it was where my wife and I went into the box and the entire audience rose and sang 'For he's a jolly good fellow . . .'. When we got outside there were crowds of our people lining the streets, to the bewilderment of Londoners. I must admit that I liked being acknowledged as a good boss. It was a far cry from our first staff outing in 1921, when I hired some charabancs and went off for a quiet country picnic.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1954 we needed to expand our closing facilities and I decided to go to Corby, a steel town where there was not much work available for women. We acquired a factory there and began taking girls to Rushden to be trained in the techniques of closing. They were keen to learn, and soon became very efficient. This venture has proved to be very profitable and there are now 250 fully trained girls at Corby. [memories of the school]

In my retirement, I have had to suffer the great loss of my wife and I have had the sad experience of seeing the company go through some bad years. Now, in the fiftieth year, John White are well back in profits and I have great respect for the energetic new team who are setting the company on the road to expansion again (although I would dearly love to be back in the factories keeping an eye on the costings!) I still keep close contacts with both the managers and the workers in the factories and attend the farewells for my old friends from time to time. John White Footwear remains a real part of my life; but I realise that other men have to make it grow in the second half century. They appear to be building well at home, and abroad. My one hope is that, like me, they will 'keep believing'. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||