|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| From interviews in 2012/2013 by Kay Collins, transcribed by Jacky Lawrence. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bruno Helsdown

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

After Schooldays

|

||||||||||||||||||||

When I was 14 I joined the Army Cadets. I was also in the Boys' Brigade and I used to go to Boys' Brigade one night a week and Army Cadets another. And I found them pretty good because I liked the Boys' Brigade because we went camp at Souldrop every August holiday and they never clashed, the camping holidays. The Army Cadets always went Jaywick Sands, near Clacton, and we had a jolly good time.

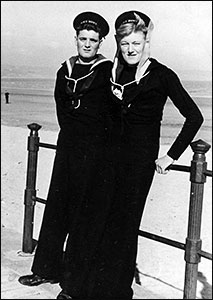

So that were the start and 6 months later, it was the happiest day of my life I'd been working down Irthlingborough, and I biked home this dark cold night and there was this big brown envelope waiting on the kitchen table and our mum said. 'I don't know what this is.' And when I opened it I'd got to go on the 1st December in 1947 to Derby for a medical to see whether I was fit enough to join the Navy. The Navy Got up the following morning, 6 o'clock, mustered all on the parade ground outside. The Petty Officer asked us if we'd all had a good night and of course we all shook our heads. He said, 'Right we're going to start getting the uniforms today but first it's a haircut and dentist and all that.' So that were the first day in the Navy sort of, having a thorough medical, dentist and haircut. The following morning, the same sort of routine. Still had another cold night and he said. "Right you're getting a taste of what Navy life's like now, anybody who doesn't want to go any further, because we're going to get your uniforms today, step forward." Half of them stepped out and I thought, well I ain't enjoying this very much but I daren't go home now after, you know, telling everybody. So I said. "We're alright." We stood fast and then we got our uniform and then we was issued with hammocks which we was, you know, shown how to sling a hammock. And that was the third night then, we had a good old comfortable night's sleep when I found a hammock was lovely and warm and comfortable. And that was my indoctrination into the Navy. We was there over Christmas 1947 because we'd only just joined. And I had the best Christmas I'd ever had, because we never had food like at home, we never had turkey or nothing like that and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Came home for New Year's Eve and of course when I got home I'd got me uniform on, that's the only time I ever wore me uniform when I was home on leave. All me mates was home, all in the services, we really had a good New Year's Eve. Went back from there and about 3 days later I went down to Weymouth for Portland. We all caught the train from Corsham to Weymouth and there must have been about 200 of us. We all lined up outside Weymouth station and we walked from Weymouth station to the Weymouth pier. Right along the sea front, caught the boats then which took us round to Portland Harbour and there I joined HMS ? What a battleship, what a sight. We were lucky really because the battleships were being phased out, I joined the Navy when we had one of the biggest Navies in the world. It really were an eye opener but the training in the Navy, I mean they didn't sort of value life. Some of the things you had to do like rowing and sailing on battleships. They had a big boom they swung out, like a telegraph pole, and you walked down there. You had a jack stay to hold on to and then there was a Jacob's ladder right down and the boats would be hanging down on the side of this. Being tall I were the first one down there, you walked along, you'd got your oilskin on, no life jacket. Got in this Jacobs ladder and you clambered down it half way, pull the boat up underneath you, jump in, and then you hold it there while everybody else comes down. In January it were blowing a gale, but it didn't stop you. So there were these cutters, there were about ten of us in there, when we all got in we'd start rowing all round Portland Harbour. Sometimes we got outside in the bay you know and I used to think, some of them were seasick, bloody soaking, and I'd think weren't it lovely when we got back in board. The nice thing about it, in March before I were due to leave, we sailed and went right round the UK. We went to Scapa Flow, that's the Orkney Islands you know, and life at sea I really liked it. I were never seasick, I used to feel a bit queer sometimes but I thoroughly enjoyed it. When I finished my training, I went to Whale Island. We done a gunnery course and I've always been a bit of a titterer, anything funny starts me laughing and if I laugh they could shoot me because I couldn't stop. I was on the parade ground one morning real serious and something happened and I started laughing. This GI came up to me, which was bloody serious in those days, and he said. "What do you thinks funny?" I said. "So and so, and so and so.' He said. "I'll soon stop you laughing boy." He says. "I want you to follow me." Now we got this shell, it was a 4.5 shell, it weighed half a hundredweight, he said "Right put that on your shoulder, I want you to double round the island." Well the island is five mile round, started off, you know, of course as you get to different points there's another bloke, a Petty Officer, and as he sees you coming he has you running up and down a bit, then you carry on. So by the time you've finished, which was 2 hours, I come back on that parade ground everybody else had dispersed to the classes. I got there and he said. "OK, I don't think you'll be laughing tomorrow morning." "No," I said. "I certainly won't be sir." So he said. "Put the shell down and join the class." I run straight to the loo and sat down there to recuperate. This is another instance, when I was on the Howe, they used to come at half past five because you were on deck at 6 o'clock. This is in January. "Out, out, out, out!" You had to come straight out and this PO went straight through our mess deck. He came back and I was still in there. "Oh," he said. "You're having a lay in are you?" he said. "Well get out and lash your hammock." So I got out and lashed my hammock. He said. "Follow me." Well we were out at sea and he said. "Right get on the foc's'le." I got up there with my hammock and the spray were coming over. It were dark, it were cold, he said. "I'll be back in a minute." Well it seemed like three days but I don't know how long it were. He come back said. "You won't be laying in tomorrow morning will you?" I said "No sir, I shall be first up." But it really were thrilling and of course from then on I done my gunnery course and passed the assault course. Then I went up to Scotland and joined the Montclare, which was in Rothsay. I was there for twelve months and the nice thing about Scotland is when I used to come home on leave, because you always had your leave, all of us, Christmas. Eventually you had three leaves and to catch the train from Williams Bay in Scotland to Glasgow, then going changing stations and coming right down to Peterborough, changing the train at Peterborough, catching the Northampton train. You know getting off at Wellingborough, you know, because there were two stations. Well, the station that served Rushden, you know, in the middle of the night and the trains then. I mean I spent a lot of the time during the seven and a half years I was in the navy on the trains.' I was on the Montclare for twelve months and I put a request in to go abroad so I got drafted back down to the UK, down to Portsmouth and I found out that I was going to be on HMS Fierce, which was a minesweeper. I had fourteen days leave, that was in October 1949 and I joined the Fierce and we spent two and a half years clearing mines all round Greece. We'd get up at four in the morning and sometimes the sea were like glass. The sun was up at four and of course, when we were sweeping, everything were closed down below decks just in case you hit a mine. So all we done was wore shorts and every time we came out of the sweep, you know, we'd all dive over the side and have a good old swim. Then, back on board you know and then after six weeks sweeping we went different places, you know for a break. We went to Port Said, because they were going to mine the Suez Canal just in case. We went ashore for two days, met all Farouk's family because he was the King then. We went to Tobruk to clear the harbours because they was all full of mines and explosives before the Italians, who'd got all the salvage rights. We had to declare that they were safe so yes, we went to Benghazi,Tobruk, Alexandria, Port Said, Casablanca . It was just after the war but the African coast was as if it was a thousand years ago, you know, it never changed. It was a wonderful experience that two and a half years I had based in Malta but to be honest we didn't spend much time in Malta. Come home on leave, met Peg, that was 1952. I went into barracks, soon as I went into barracks it was the Coronation coming up. So they put me in the Royal Guard. I got on the Royal Guard, stood on the barrack square, in barracks. We got there once they pick you out for the Royal Guard, you know, and they sorted you all out. As soon as I come back off leave the PO, the regulation people, stood on the gate and if you looked suitable, stand out, fall in here, you know.

Well nobody got watches on and you'd be standing there and you could talk. We were standing at ease and the day, you'd think well it's got to be 10 o'clock, and you'd say. "What's the time?" to the PO and he'd say. "Five to nine." Well the day seemed like a week. We got a break at half past ten, ten minutes, back on the parade ground again. Twelve 'til one dinner, back on the parade ground again. This was started on the Monday, on the Friday I was just walking back to me billet and I had to go through the draft office. I see a big notice there 'Wanted, butchers for small ships'. I went into the draft officer said. "What's this er, what's this butchers doing." He says. "We want volunteers from butchers for small ships, why are you interested?'" So I said. "Yes, I could be." He said. "What job you got now because you're all dressed up." I said "I'm just going ashore," He said "Alright then, put your name down." I said "Well when do they leave?' He said "Be outside your barrack room at seven o'clock Monday morning and you'll catch a train to Aldershot, you're going to the Army barracks and that's where you're going to butcher." "Fair enough," I said and I thought, well, I shall be gone before they miss me. Because if they ever found out that's what I were going to do they'd have stopped it. Because once you're doing the Royal Guard you can't get out of it. I regretted it in some respects because going to the Coronation. But anyway I goes up to Aldershot, the Royal Army Ordinance Catering Corps and it was a civilian butcher who taught us. These first couple of days there we was learnt to slaughter cattle which I didn't go much on. Well, I nearly went vegetarian but anyway it were the best thing I ever done. We made sausages, we made pressed beef, corned beef, every aspect of the butcher's life. We were there for five weeks and of course we were only three matelots in an Army camp full of trainees, ATS women and just ordinary soldiers. We was based in a little unit on our own and of course these ATS girls, we was a novelty to them, they used to bring us jugs of tea as soon as you got up in the morning. We had all special grub and we used to go drinking with them at night. But cor, what an hard bunch of bloody girls they were, you know, I ain't saying they was some of the roughest women I'd ever met but they were a bloody coarse lot. When I come back I went back in barracks in the B stream cutting beef up and I had six months in barracks. Then I had a draft ship down to Portland to catch this frigate, Headingham Castle, and the good thing about it, one of the chiefs, the coxswain on there he was on the Fierce with me. So I spent four and a half years with a coxswain you know. And of course being a butcher on there my only other job was when we come out of harbour I was on the wheel, or if he were on the wheel, on the telegraphs, that's the only duty I had to do. I had a butcher's block, with canvas screen round it, which I used to have to roll up. I'd get my carcass out the deep freeze the day before and take it in my little beef screen to let it thaw out. Well we was at sea most days, taking trainees out to learn them ASDICS, and it would be blowing and raining and there'd be me up there sawing a hind quarter up or hanging a pig up. I'd cut it all up in portions and then all the officers come up. There's so and so you know because if you had a leg of pork this week next Sunday, because everybody wanted a leg of pork on Sunday, but there's only two legs. I used to do the shoulders, bone them and tie them all up. Every day, when we was at sea, the Skip would come round, the captain that is, and he'd say. "How are things Helsdown?" And I'd say "Alright sir." "What are we on tomorrow?" "We're on pork sir." "Oh dear, oh dear, you know a lot of people don't like pork, it's a bit greasy, especially when it's rough at sea." He came by one day and he said. "We're going to have a little bit of a relaxed period. We can go wherever we like. Where do you think you'd like to go?" I said "Let's go to Jersey because we should be getting some new potatoes in now. And I can put the spud locker up the, top the spud locker up with new spuds." So we went to Jersey and that's where everybody loved people. The dance halls were free, the cinemas were free and every night hundreds come down just to see the boat alongside, it was a good old week. Another highlight was, coming into Portland harbour one night, he come down and said. "Helsdown, I've just learned you've done a bit of rowing." I said "Yes sir." He said "We've got the regatta coming up." Now the regatta is always a fleet, home fleet. Used to assemble in Portland Harbour and each had their boat races. And there'd be the officers had a crew, the seamen had a crew, the stokers had a crew, and then there were the miscellaneous, that was all different departments. He said "There's only a hundred of us on this small ship I don't think we've got no chance of ever picking a cup up. But, if you can get a team together the only chance is a seamen's cup. I said "Yes, I think I can do that. What I want you to do, when we're coming in harbour at night, just drop us two mile out at Portland harbour and we'll see what we're like rowing in. So I picked a crew out that I thought would be suitable and we started training. Every night we'd come in, five nights a week, he'd drop us off at two miles, even if it were rough. They said, "We're not blooming well going down tonight are we?" And I said, "Yes, because if it's rough on the day of the regatta we've got to get used to it." After a bit I said "OK we're going to get it together now. What I want you to do is just increase the revs a little bit, go a little bit faster." They usually sail at about, coming in harbour, at about a thousand revs. So I said 'Just put it up a bit, say a thousand and twenty.' The boat would be pulling away a little bit and they'd think we were slacking and that's what we done every night. And do you know what, I'd trained this team and I said to the bloke who was coxswain, I said 'Now look, for God's sake steer a straight course.' Told him what to aim for, the other side of the harbour, because if you don't keep a straight course it will lose us the race, which he did. And the good thing about it was we won the seamen's cup and our skipper was so pleased with me I couldn't do a thing wrong. And on the final day when I left the navy they put a party on for me, which was unheard of, because nobody, well you just got demobbed. You see that's how popular I were on board this ship. And the day, the night before I was due to come off, early next morning, because this party were two or three days before I was due to come off the boat he said. 'Helsdown,' he said 'Why don't you sign on,' he said. 'Because you're the calibre of man we want in the navy today,' he said. He said, you know, he said. 'You've had chance to be promoted but you refused it, you know, because you've been happy where you were,' he said. 'Why don't you make the navy a career?' I said 'Well sir, I broke my apprenticeship to join the navy from Marriotts, the builders, and the boss said as soon as you come out, he said, if you come back you can start your apprenticeship again from where you left off you know.' I said. 'Well after seven years, or seven and a half years if I keep on any longer I shall just go out the Navy, perhaps twenty two years but I shan't have a trade.' So I said, 'That's the reason.' So he said, 'You're going back to be ?? I said. 'Oh yes sir.' So he said, 'Well you don't want to go in the Police Force or fire brigade.' He said, 'If you want to earn some money,' he said. 'I can get you on a whaler.' Because then whalers were going up after bloody whales and he said 'It's a stinking job but God you're talking about a £1000 a month.' 'Christ,' I said, 'No.' So I did come out then, and on the morning I came out I stood on the jetty and the ship were due to sail out and I'd got all my kit, hammock, my kit bag and I just stood there. And because it were open bridge them times then you see he let down the forward, to let you aft. He said, 'Goodbye Tanky!' through his megaphone, you know, and all the ship's company had lined up, because they used to line up leaving harbour. 'Now,' he said 'Give Tanky a wave.' Because that's what they called me. 'Give Tanky a wave.' And they all shouted. 'You'll be bloody sorry!' It's the lowest I'd ever been. If that old ship had come back and said get back on board you silly bugger I would have done. Oh I'd never felt so low in all my life to think that now. Because I went straight in barracks, I were in there two days, got demobbed and really and truly speaking I think that was one of the lowest points of my life. I thoroughly enjoyed it and even next, in two weeks time, I'm going to Hayling Island, Delreece? And there's still ten blokes who are still alive today, the oldest one must be ninety and I'm perhaps one of the youngest ones at eighty two. Served together in Malta for two and a half years, we still meet up every year and so that finished my naval career. But I tell you what it was the happiest period of my life, I wouldn't have missed it for the world.

Things were very different in them days, I mean before I went abroad there was dances at the 'Mill, people used to collect outside where the Ritz were. There were three cinemas you know so everybody went pictures. Everybody used to get outside the Rose and Crown Saturday night because the Pink 'un used to be there. But all that were changed you know, people had started watching television. And I found out from when I went abroad, and when I got demobbed in the Navy, the biggest change this country had ever had, because everything, and I was amazed at the start to look up and see all these things on British chimneys, and they were televisions. There was nobody in the pubs during the week, everybody was watching television, nobody went out. And the only time there were a dance at the Windmill it was all Rock & Roll, you know. So I found what a difference it was, but the good thing there was plenty of work about. I went back onto Marriott's for about nine months and then I decided that the bonus weren't all that good and somebody approached me to see whether I wanted to go to Luton, Wimpeys, who were doing a big housing estate. Which I said, yes, and the average wage on Marriott's was £11 but if I went to Luton it was London rate and I were going to get £18 a week, which was a hell of a lot of money in them days because your average wage was only about £10 or £11. So I started there, I got a gang of blokes together and we decided to take different contracts on. One of the main and earliest ones were Newport Pagnell, I took this field on we set the roads out and done everything and that really got me into building. So right through my building career I started doing odd jobs on weekends and nights to get a bit of extra money. I bought my first car in 1956 which was a Morris 8 Series E pre-war car you know. And we'd fill it up with petrol and when that five gallon had gone we used to have to put it back in the garage because we couldn't afford to run it no more. So, if we went Clacton for the day on a Sunday it stopped in the garage for the next two weeks, that's how you know how it was. But of course we walked everywhere even when Jackie was a little girl and she, you know, if we wanted to see her mum and dad, Peggy used to catch the bus, that's my wife. And I would walk from here to Finedon pushing the pram, Sundays. And then we'd have Sunday dinner and Sunday tea and then I'd walk back again, you know. So this is how it was you know because we pursed on the council house, our first council house, was up Allen Road just been built. And so, consequently, when I left Marriott's I did spend a bit of time on Windsors and help build the first council house that I moved into before I went to Wimpeys at Luton.And so yes we had eleven years up Allen Road and always trying to earn some money. Everybody had coal fires at them times, so every Sunday morning somebody would come round and wanted their chimney swept. So I'd go and sweep their chimney and it were the dirtiest bloody job, you know. So I'd come home about half past eleven, get straight into the bath and that were getting ready for Sunday, because Sundays in the summer we always went out for the afternoon. After meeting my daughter who went to Sunday School in Zoony Green's factory, that was part of the St. Mary's Church. We'd always go over to Wicksteed Park or Billing or Overstone, always went over and took our tea on a lovely summer's Sunday afternoon. And that's what it was about, it were the simple things in life that we thoroughly enjoyed. Of course we progressed from there and I bought my second car. I sold the first car for £100, what I could get for it, and bought another car second hand, a little bit better for £150. And that's how life went on, as soon as I got a bit of money and, after I'd had my car twelve months, I gradually upped it until 1959, when I bought my first van and adapted it with a seat in the back so it looked like a car. We put side windows in, just cut the panels out, which you was allowed to do them days. And, yes, and it was a very happy time, nobody had got nothing. I had a lorry that, when I started on my own, and we used to enter it in the carnivals, when Rushden had its carnivals. Used to start down Spencer Park, it was a really good day, and every factory put a float in, you know. And we used to. After ten years up Allen Road I had the chance to buy a piece of allotment in Quorn Road in Rushden. I bought this bit of allotment for £500 and built a bungalow on it, done everything myself and that's the only time I've ever had a mortgage in my life. I put brand new furniture, carpets, curtains and everything. And I done all that for £2000, built the place, furnished it all out and that were the first time I put a swimming pool in the back of the house, and then Jackie would be about ten years old, she joined the girl guides at St. Peter's Church. So getting back to the float situation, being as I'd got a lorry then and I was doing fair bits of jobs that I'd started on my own by then, sub-contracting, we used to do. Quorn Road used to decorate a lorry, my lorry, and you know, used to decorate it all on a Friday before the Saturday were, and entered it in the carnival. And that's it were such a happy time, nobody worried about what other folks had got, you know. Peggy didn't go to work in them days, you know, and the children used to come home for school dinners. And because by that time Jackie had been down at the infants along Hayway, so she came home for dinner and tea, you know. If some children used to go school dinners, which they provided school dinners for children whose mothers went to work. So, consequently moving on, we built this house down Quorn Road and yes it was just the same happy going on. And I was doing jobs at night, accumulating a bit of money, you know, and after a short space of time I paid my mortgage off. And luckily, for the rest of my life, I've never, ever had a mortgage because the same when we moved down here. We was down Quorn Road from '63 to 1980 and then I had a chance to buy the present piece of land where I am now. It cost £21,000 and it was sheer coincidental that I got this bit of ground because, and that's how my life's been, destiny's controlled my life completely. And everything what's happened is soon to be, I was pretty lucky, you know. Like I bought the bit of ground down Quorn Road because somebody else couldn't afford it, and I could afford it, because it was £500. But this bit of ground for £21,000, I didn't know nothing about it until I went down the Ski Club, which was a very popular place in my younger days when I were about thirty, forty I should say. And I was just coming out the Ski Club and somebody told me that this piece of ground was on the market. I hadn't heard about it and just as I was told Mick Neville came walking by and he was handling the sale, so we had a chat about it, you know, and he said 'But it's going to public auction.' So I said 'Well what are they hoping for?' He said 'If it doesn't get £18,000 they're not going to sell it.' I said, 'Oh!' So I said, 'Well offer him twenty.' 'Fair enough,' he said. So Monday morning at eight o'clock I were waiting outside his office. 'Bugger me,' he says. 'What are you waiting for?' I said 'Get that bloke on the phone' which he did, it were a bloke named Coley. So he got him on the phone and he wasn't interested, no, no, it's going public auction. So anyway on the Tuesday night I was playing squash down the Ski Club and it was a thing, that if it's in my mind for any length of time, I'm got to sort of act. So I said to the bloke I were playing squash with. 'I'll be back in about ten minutes, quarter of an hour.' Jumped in my car, come over the road, because that's where he lived, and he didn't want to see me for the start. But I said. 'Just give me two minutes of your time.' And I offered him £20,000, he'd got no hassle of paying the estate agent and all this and that he said, you know, and he agreed that if I gave him £21,000 that would do.

And in the meantime, by the time I'd raised it, I'd sold Quorn Road. I'd sold that within a week and I moved into a little old house which I'd built up Washbrook Road, you know. And which my wife weren't very happy with, but I promised her that we'd have this house in twelve months. Two and a half years later was when we moved here, but it was really from then on I made it a family home and we thoroughly enjoyed it, you know, since we've been down here. And we've had many do's, we've put on a do every year for the Lifeboat Association. We've had the Conservatives down here, we had the Museum which come last year, and it were pretty successful, weren't it. Everybody enjoyed it, so consequently it's been a very happy period of my life. There's a lot more I could fill in, but one of the interesting factors, being a local builder in Rushden, and always doing different things I found that people was always approaching me. Either if they were doing things themselves, could you come and have a look, I've just started building a base for a greenhouse, for arguments sake, and I'm in trouble can you come and put me right? And I found, when I was down Quorn Road, and then here, people were consistently doing that. Now one of the things too, as I've started getting on a bit in life, I started Toseland's builders up. I financed Toseland's Builders Merchants for the first, well it was, that was another accident. Because what happened were, I was over having a drink over Higham with the Naval Association and Len Toseland came in. And I knew he was going to get the sack from Ellis and Everard's and I didn't, you know. And he said he didn't know what he were going to do. And I said 'Start up on your own,' and he said 'I'd love to but I haven't got no money.' I said 'How much do you think it will cost?' He said. 'I don't know, I'll let you know.' Twenty four hours later, when I was having me tea, he came and said. 'Were you serious last night?' I said 'Yes'. He said 'You couldn't furnish me with about £8000 could you?' 'I said 'Yes.' He said. 'If you could lend me £8000 have we got anywhere to start up with?' I said 'Yes, we got a lot of ground up Alexandra Estate.' That's how we started Toseland's up. And we started Toseland's, we worked from the garden fields up Alexandra, what's its name, for the start. And then I was lucky enough to buy and financed the yard up Queen Street, which belonged to Whittington and Major's. And by this time then Toseland's, then I changed because I had to when I lent the £8000, and I then changed it over to Toseland's on an industrial mortgage. So I got my money back because at that time we was making a fair bit of money and we got an industrial mortgage. And then the next thing when we was working up the yard, up Queen Street, I'd found out that the United Counties Bus Garage was on the market and they wanted £80,000 for it. Well there again you know I went to see the bank manager and he said. 'That's way beyond my reach, you know, what can you put down?' I said 'I can give you the deeds to the bus garage.' 'Yes, but that's not enough,' he said. I give him the deeds to this house, all me insurance policies to secure the £80,000 we wanted for the bus garage, so that's how we bought the bus garage. But I found out after a time working for Toseland's I got no satisfaction out of buying a bag I bought for £1 and selling it for £2. I still loved building and I still carried on building, I devoted two days a week delivering on Toseland's, when they were busy, but the other time I was still doing me building work. But after a time I didn't do much on Toseland's, so I came out of Toseland's. And after a bit of a struggle, and I didn't quite get financially what I wanted, but then it all went to Len Toseland, he was on his own. Then he got a mortgage and we gave him a good start so I came out. Now since then every organisation in Rushden has approached me because being as I live where I live everybody thinks I'm a millionaire. The first people to come and see me, or one of the first, were the Bowling Club and they wanted an indoor bowls. They've got the ground but the old Rushden Town Bowling Club would not lend them any money, or give them any money to build an indoor bowling rink. So they came to see me, to see if I'd finance it. Well after a bit I said no, come and see me in a week's time, which they did. And I said. 'No I ain't going to tie my money up in something like that you know you rent it.' But I said 'Here you are.' And this was in, must have been about 1980 something. I said 'Here's a cheque for £1000, you can go round Rushden and tell everybody that Bruno's given you a cheque for £1000. If you can get twenty more people like me you've got £20,000. Go and see the bank manager, he will lend you £20,000 so you're up to £40,000. I've been in touch with the Sports Council, if you can get something in writing they will give you a grant from the sports centre. I am doing some pub work, now I've had a word with the boss of Wells, the brewery at Bedford. Providing you have their beer they'll furnish all the bar and provide a lot of furniture and so forth.' So with a bit of pulling and pushing everything started folding in and that's what happened. The same happened with the Wesleyan Chapel extension at the back. They came and see me said. 'Bruno we're never going to get that extension built because every time we go and get some money, you know a bit of money together, the price of the project's gone up. Marriott's want a £100,000, all we've got is £60,000. But he said 'Could you do us something for £60,000.' 'Come back,' I said. He said 'We are promised a lot of money.' But I said 'Well nobody is going to give you any money until they can see a bit of progress on the site. Come back and see me in a week and I'll draw a plan up what I think will be, you know, suitable and fit your financial situation.' Which they did. I promised I'd do the shell and the floor windows and everything for the £60,000. Then they'd have to find the money for the plumbing, decorating and specialised floor and the kitchen units. But I had been in touch with Tesco's and they, no, Texas, and they had, they'd got a charitable organisation. Any charitable organisation can approach them and they will give, they'll supply the kitchen furniture, you know, sink and everything and drawers and so forth by pack, free of charge. So things started progressing and yes, half the committee wondered how I could do it at £60,000 when Marriott's wanted £100,000 plus. But they were going to do a complete job, plumbing, electric, I weren't you know. And I said. 'Well, that's my problem. If I found out that I've got your building half done and I've run out of money I'll still make sure it's completed.' And so, yes, we got that done, I done it in twelve weeks, that place were built in twelve weeks. And ever since then, the football club come and see me, could you help us. That was up Hayden Road, could you help us put the new roof on, you know. So I give them a donation which was, you know. 'Sarah's mum come to see me when she first wanted to start the museum and she said. 'Bruno I'd like to start a museum in Rushden.' And I said 'Yes what a pity, we had Hall Park when I was a child before the war. Up Hall Park we had everything, we had a big tray of drawers with every bird's egg in, you know. We had a penny farthing bike, we had a three wheeled bike, we had a bloke in armour.' The memorabilia we had and of course what happened were, soon as the Yanks come, we just chucked it all. Went down the tip which, the tip at that time was only a small tip, was up Bedford Road, Rushden, where the Rugby Club is now. Because nobody threw any rubbish about like they do today. When the ashcart come round sometimes people's ashbin was empty, but anyway that's where it all went. So when Sarah's mother came to see me she said. I said. 'Well have you got anywhere?' She said 'Well we think we can rent Sanders' old carpenter's shed just off Rectory Road.' So I said 'Well.....' So she said 'We've tried to get some donations.' I said 'How much do you want?' She said 'Dare I ask you for £50.' Now I don't know, this is going back a hell of a while I said. 'No problem here you are.' I give her a cheque for £50 and Sarah even said about it the other week. She said 'I'm still got the record of what our mum give me because obviously down there, and I thought over the years that would be it. I never heard no more from you know from the museum until we started getting things together.' And that's when they started up the Hall Park with one of their premises and the good thing about it Sarah came round then and said. 'Bruno you wouldn't take that big wall out, would you?' I said 'Yes.' Which I did, she said 'You wouldn't give me a estimate of £3000?' I said 'Yes.' 'So we can get a grant.' Which they did and I didn't want nothing for doing it and of course we progressed for that. So all my life has been, there's people and different blokes have come up. Mick Fuller came up, Ethel Young, who was a builder's and do-it-yourself shop. When she packed up she give him all the work that they had come in but he hadn't got no money to start up on his own. I started him on his own. I started a bloke named Pete Dawson up, he were the first one to start valeting cars, had a good business, you know, until he had a heart attack and went down. And the people who come round and asked for money from me, being as I live where I live, everybody thinks I've got more money than I actually have. But I've always had a great satisfaction, I'm a giver not a receiver. Because it's gives me great satisfaction to think that I've helped somebody along the way, and I've been fortunate enough to be able to do it. So I've got a great satisfaction there and I've never been a greedy bloke, you know. If I've been done a job for anybody, and I thought they hadn't got much money, you know, I haven't charged them much money. But at one time, when the Telegraph used to come out, they used to publish the wills and many a time, Christ I did that job for next to nothing and he'd got more money than I'd ever had, you know. And one typical was Mrs Elliott, her husband were the manager of the Echo and Argus Rushden. And they lived in a house down Spencer Road, Ken Joyce had it after them. And she said, you know, 'Would you put me a nice concrete path in.' I said 'Yes,' and she says 'How much is it?' I mean this is how much things were in them days I says. But it was only half a day's job, I think we charged about £5 for the labour, about £5 for materials. 'You blooming old Jew,' she says. 'I'm not giving you £10 for doing that.' She said 'You know here's £6 and be satisfied.' And this is how some people were in them days, you know. And I didn't make no fuss or bother about it. You know, I used to think, Christ if she ever asks me again. Another case Bill Jones, I won't tell you who he was, what he done, but he'd been presented with a greenhouse and he said. 'Bruno you couldn't come and put the base in could you?' I said 'Yes.' So when I went to put the base in. I said 'Bill this ground is too hard to dig.' I said 'Leave it, let me soak it up because I can dig it easy.' I said 'Because if I put a bit of foundation in for the greenhouse and it settles with wet weather the glass will all crack and everything.' 'No,' he said 'I want it up now, straight away.' I said 'Well, fair enough, but I shan't be responsible if anything, you know, any settlement, which I done. He had all his friends round you see and some of them said, 'Phew! Pity you didn't get a professional to put it up for you.' I said 'I never put the greenhouse up I only done the base you know.' So he weren't very happy with it and I done the base for £10. 'Don't pay me.' I said 'If you ain't happy no, no, Bill I don't want if you're not satisfied with what I've done you have it for nothing.' On the following winter a hell of a gale, it blew half his roof off and he only lived opposite us down Quorn Road said. 'Bruno do me a favour will you.' I said 'What's that Bill?' He said 'Look at me roof,' he said. 'Can you get at it right away,' I says, 'I'd go and get a professional builder if I were you, Bill,' I said 'You know you weren't very happy with the last job I done, you know.' Just shut the door on him, course he stood outside, you know, you rotten so and so! And it's been a very, very, interesting life !!!!

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|