|

Introduction

|

|

The house in Fitzwilliam Street

|

W. E. Lockie & Son, of Rushden, Northamptonshire, was a small, family-owned engineering firm that (almost) survived all the perils of the 20th century. Three generations of Lockies, working together at one time, kept the business afloat in peacetime and war. All this ended in August, 1996, when batchelor Ted Lockie, aged 76, died after burns received in a fire on his holiday narrow-boat. A clearance sale was arranged for the Autumn.

Saturday, 30th November, was raw and sleety, but a curious crowd squeezed into the Lockies' bleak workshop, our saleroom for the day.

At the preview, I had leafed through a flaky postcard album, thinking that another lot looked more interesting. Described as 'Russian Photographs', it was a pair of small, cardboard soap-boxes, crammed with tiny, curled prints. The custodian told me they had belonged to the deceased's father, another Ted, who had served in Russia during the Great War, 'something to do with armoured cars, I think'.

When the prints came up it was easy, only one other bidder opposed me and he dropped out at double figures, the soap-boxes were mine but the postcards went elsewhere. At home, a closer examination convinced me that the prints had historical significance. Pencilled locations on their backs ranged from the Arctic Circle to the Black Sea. If Ted senior (Ted from now on) had taken these snaps, he must have got about a bit. I wrote to the Imperial War Museum, who asked to see the prints.

Before they replied, the postcards reappeared: the successful bidder thought I might be interested in a deal. His hunch was correct, the prints and cards belonged together.

A simple postcard message can recall the past more vividly than reams of purple prose.

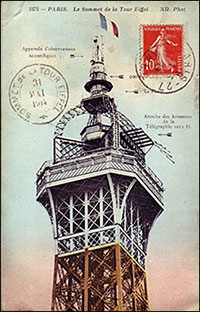

In 1914, Ted Lockie was 20 years old and in love. A cheerful optimist by nature, he probably hadn't a care in the world when he sent his sweetheart, Doris Ette, a postcard from Paris on the 31st May:

"Dear Doro, I am at the top of the Eiffel Tower writing this. It is 1000 feet high and a wonderful sight. Your's Ted."

|

|

|

|

|

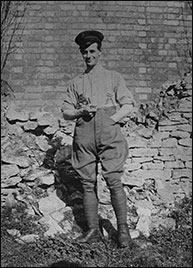

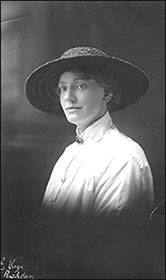

| These two photos were amongst the many postcards that Ted had sent to Doris during his time in Russia.

Ted had married Doris in the Fulham area in 1915 before he left England.

Ada and Doris were daughters of Joseph Ette of Grove Road.

|

|

|

Ada Ette - sister of Doris

born 1886

|

Doris (nee Ette) whom he married in 1915

|

By high summer, advancing German armies were stalled close to the gates of that city. A French friend of Ted's set the scene on a view card from the Auvergne, dated 18.9.14:

"I am in the south of France for a few days to see my brother wounded. He can thank God, he escaped many times to the death, he has many holes of bullets in his coat, now he is quite all right and is ready to go again the Germans. This damned people thought they would come easily to Paris, but they did not think, Joffre was a good general and the brave English were there. Now we are going on Berlin, where I hope to see you, to drink a good glass of beer but without pay. Kind Regards, Your ami, Victor."

Lockie and The Lanchesters: The R.N.A.S.In Tsarist Russia

|

|

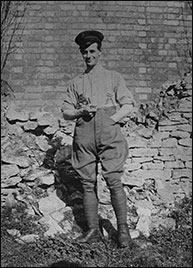

Petty Officer Wm Edw Lockie RNAS

|

Ted joined up two months later, with Doris's cousin, Charlie, and two more Rushden men. Motoring was still a novelty, so their choice of service merited a mention in the Rushden "Echo" of 20.11.14: 'Each has to qualify in motor driving in order to be able to use a motor cycle & side car bearing a maxim gun. The pay is at the rate of £3 a week.' This was extraordinarily good money for the times, and we shall see why. His next card, as a serviceman, is a typically French glamour photo sent to his wife and dated 20.7.15:

'Thanks for parcel. Everything was alright. I will send letter soon. Send another pillow as soon as possible. Give my regards to the dear old orchestra (Ted played cello in Rushden Town String Band), and send a few fags when you like. Many thanks from my pals for cake, etc. Keep smiling, Yours Ted.'

Nothing unusual in this breezy message - except the censor's signature: 'Lt. A. H. Prothero, R.N.V.R.' So what was the Royal Navy doing on the Western Front? The answer to this, and the key to interpreting Ted's photos and postcards, lay in Bryan Perrett and Anthony Lord's book ,'The Czar's British Squadron' (Wm. Kimber, 1981), which I found in our local library.

The Royal Naval Armoured Car Division, a wing of the new Royal Naval Air Service, was formed in October, 1914 by Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill had been impressed by the performance of a R.N.A.S. squadron in Belgium, which; being short of planes, had followed the Belgians' example by converting civilian touring cars to military uses, such as rescuing downed pilots.

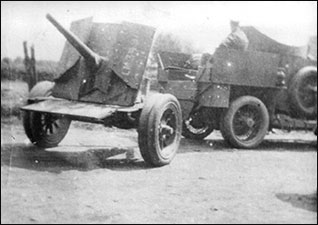

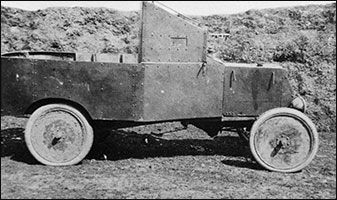

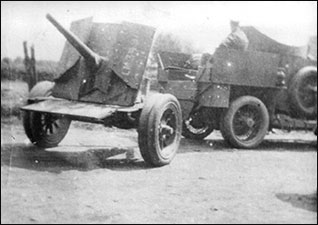

The Division's cars, mainly Lanchesters and Rolls Royces, were commandeered countrywide, then strengthened to carry armour plate and a revolving machine gun turret. Heavier cars carried a 3-pounder gun to deal with enemy strongpoints. Operational self-sufficiency decreed that each squadron of 12 fighting vehicles had its own mobile workshop, ambulance and wireless truck.

Within a few months, there were 15 squadrons: 6 equipped with machine-gun armed motorcycles, 6 with Rolls-Royces and 3 with Lanchesters. Drivers and mechanics were harder to find, not least because the R.N.A.S. was competing with the Army for them. The Navy outbid its rival by offering qualified recruits the rank and pay of Petty Officer Mechanic.

|

|

Oliver Locker Lampson

|

A charismatic leader was needed now and he came in the person of Oliver Locker Lampson M.P., a 34-year-old who held North Huntingdonshire for the Unionist (Conservative) Party. With clandestine help from the ... Ulster Unionists, he had raised an armoured car squadron from friends and constituents. Designated No.15, it was sent to East Anglia when a German invasion seemed possible in December 1914. Later, the squadrons moved abroad to Africa, Gallipoli and Flanders, where they met with varying success. Trench warfare did not suit them, and the Dardanelles fiasco, which caused Churchill's resignation, lost them their strongest ally at the Admiralty. Virtually friendless, the Division was about to be handed over, piecemeal, to the Army, when a chance conversation with a senior Russian officer at a French dinner party in the Autumn of 1915 gave Locker Lampson an idea. Conditions on the Eastern Front favoured armoured cars, the Russian told him Belgium had sent a squadron, so why not Britain?

The request was made formal, and Locker Lampson submitted it with his own. He was in luck, the Admiralty, smarting from the Navy's failure in the Dardanelles, was keen to restore its prestige: a complete division of 3 squadrons, including No. 15, would be sent to Russia before Winter froze them out.

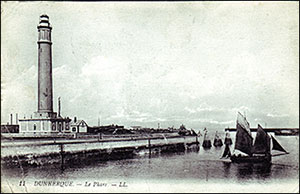

Meanwhile, Ted Lockie had been home from 'somewhere in France', where, he told the 'Echo' of 27th August 1915, he was 'on the advanced repair staff, repairing motor-cars', but would say no more. However, his next postcard to Doris, dated 10th September, is an 'L.L.' view of the lighthouse at Dunkirk, where a squadron was based:

'I am quite alright, thought you would like a card now and then. Thanks for letter. No need to worry, just lay upon the pillow and read the Daily Mirror. Ted.' Surgeon G. Legg, R.N. has censored it.

|

|

Dunkirk Lighthouse

|

The British Armoured Car Division, as it was called in Russia, was placed under Locker Lampson's command. Six weeks were needed to equip with Lanchester cars and winter clothing, followed by a short spell of leave, before the unit mustered at Euston Station in late November 1915.

Ted went with them. His next card, dated 27th. November, is a RP street scene of St. Peter's Cathedral, Liverpool: 'Left Euston at 12.30 arrived at Liverpool 7.30 next morning, and were billeted about the place. My address here is: P/O W. E. Lockie, c/o Grenville Hotel, 10, Grenville Street South, Liverpool. I may be here until Wednesday. Put your address on letter for return in case I'm gone. Ted.'

|

|

|

The postcard from Liverpool

|

Although he could not know it, Ted was about to play his part in a passage of arms unique in Britain's military history.

End of Part 1.

Part Two

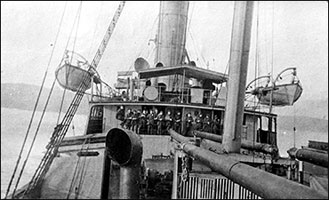

Heartened by messages of goodwill from King George V and Rudyard Kipling, the Division's 500 men boarded SS 'Umona' on Wednesday, 1st December, 1915. In peacetime, the liner had accommodation for only 75 crew and 58 passengers, so an uncomfortable voyage was assured even if the weather was kind.

It wasn't. After a 36 hour delay due to U-boat sightings in Liverpool Bay, they sailed on the 3rd December, heading north along the Ulster coastline. On the evening of the 5th, 'Umona' ran into a storm that nearly sank her. Ted's eyewitness account was published in the 'Rushden Echo' on the 17th March, 1916, when he was home on leave:

'We lost a couple of lifeboats and several temporary buildings on the well decks (were) smashed to splinters by the tremendous seas that broke over us... The situation became critical, over 500 men, including experienced sailors, were sick as horses. The Captain never left the bridge for over 24 hours, and at one time the ship listed to port so far that it was feared she would capsize... The sanitary conditions were bad, the water froze, and the ship was covered in snow and ice...'

Three days later, the storm blew itself out, though life aboard the battered 'Umona' remained unpleasant. Below, in a stinking shambles, the men were allowed no heat or smokes on account of the ammunition stored beneath them. Rounding the North Cape, further north than any British Expeditionary Force before them, they sang the National Anthem in commemoration. Ten days out from Liverpool, they anchored in Ukansky Bay to make urgent repairs.

The expedition might have ended here. The White Sea was frozen, closing their route to Archangel, from where came orders for them to return home. Sensing it was now or never, Locker Lampson connived with the Senior Medical Officer to persuade the Admiralty that a pneumonia epidemic was likely unless they could get the men ashore. His ploy succeeded: he was allowed to proceed to the ice-free port of Alexandrovsk, better known to World War Two Arctic convoys as Murmansk, which they reached on Christmas Day.

They began to land men, 'who were billeted among the Laplanders'. Rations were augmented with black bread and reindeer meat, which Ted found 'bitter and unpalatable'. Locker Lampson kept them fit with training sessions and helping the Russians develop the base. The storm at sea had damaged many armoured cars, so these, together with the repair staff and the sick, were brought home.

Ted was busy in the ship's sick-bay, but when they called at Lerwick, in the Shetlands, to discharge a patient, he found time to send Doris a romantic postcard, printed in Germany!:

Feb.21.'16. Dear Kid, Just a line hoping you are well etc. I have arrived back again and have a few minutes ashore, expect to be home shortly. Ted'.

They reached Newport, Mon., on the 26th, and Ted sent a RP of the transporter bridge:

'Dear Kid, Have arrived all safe and sound at Newport. Am just having a walk round. Snowing badly, expect to get a few days leave soon. Ted'.

Newport was the Division's home base and workshop. A week was needed to unload the ship and discharge patients before Ted got his leave; he was unaware that the expedition was again in jeopardy.

But someone, probably Churchill, had tipped off Locker Lampson: the Admiralty, faced with an expensive refit, was considering pulling out of Russia. For the British Commander, it posed an humiliating setback to his career. Luckily, he held a trump card, a letter from King George to his cousin, Tsar Nicholas II; now, he decided, was the time to deliver it - in person - by way of England, Norway and Sweden.

A fortnight later, at the Russian GHQ (Stavka), at Mogilev, where Nicholas spent most of his time, Locker Lampson found him charming and compliant. No mean charmer himself, the Englishman not only won his plea for the Division to be allowed to remain in Russia, but was twice invited to dine with the Royal Family.

In April, he returned to Alexandrovsk aboard 'Umona'; taking with him the new armoured cars and Ted Lockie. The Spring thaw allowed them to complete their interrupted voyage to Archangel, where they came ashore to a rousing welcome, on the 30th May. Ted's first Russian card, a view on the River Dwina with a hasty message, was dated the 1st June, the day the Division entrained for Moscow.

|

|

Ted standing right with some of the Russians in 1916

|

The journey south, aboard primitive rolling stock, took almost five days to traverse a vast landscape of endless forest, dotted with lakes and rustic villages. In Moscow, they were received by the Grand Duchess Elizabeth, sister of the Tsarina. The British were feted wherever they went, but were shocked by the pitiful condition of the poor and the war-wounded they saw in Moscow's back streets.

On the 7th June, the visit culminated in a march to the English church, watched by huge crowds, followed by a farewell banquet in the Summer Gardens. From now on, they were part of the Tsar's Army, and their orders were to entrain for Trans-Caucasia.

Heading south again, into, ever-warmer weather, the Division, minus its cars, was approaching a remote battleground on the Russo-Turkish border. In the wild country beyond the Caucasus mountains, Turks and Russians had clashed fiercely, and the Turks had had the worst of it. Oil was the ultimate prize and, to safeguard their supplies, Britain and Russia had, respectively occupied the north and south of neighbouring Persia (Iran). To add to the confusion, revolting Armenians, inflamed by Turkish massacres, and dissident Russian Kurds were fighting their own battles.

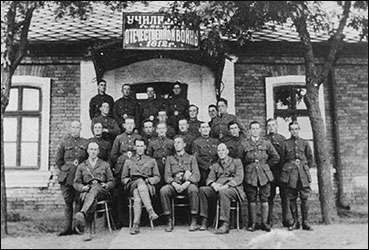

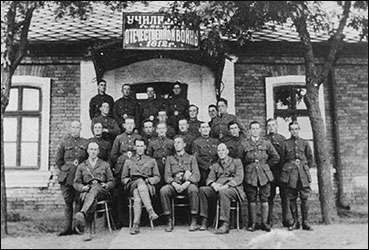

Journey's end came on the 13th June at Vladikavkas, in Georgia, Stalin's birthplace. Here, the Division was comfortably quartered in the 'Patriotic Warrior of 1812 Officer Training College', which features to Odessa, before returning to England to plead for replacements for the Lanchesters, which had low ground clearance.

|

Group of Medics outside a Training College at Vladikavkas

in August 1916

Locker Lampson (seated 2nd from left) - Ted (extreme right)

|

Meanwhile, the squadrons found action again as part of Russia's aid to the faltering Rumanians, whose old foe, Bulgaria, had attacked them on the 1st September. They left Odessa on the 14th November, at first by rail, and then up the Danube on grain barges to Hirsova, where Siberian troops were fending off the advancing Bulgarians.

|

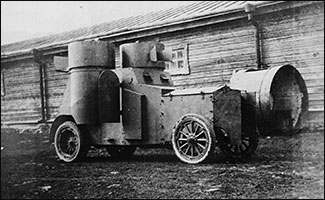

|

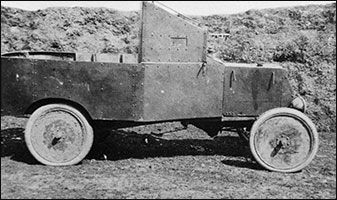

Lanchester towing a 3-pounder gun

|

The Lanchesters suffered casualties in the ensuing battles: though almost impervious to small-arms fire, they were vulnerable to artillery. Slowly, the poorly equipped Russians were forced back to Braila and Galatz, faraway places that feature, nonetheless, among Ted's photos.

After Bucharest fell, on the 6th December, a new base was established at Tiraspol, on the River Dnestr some 50 miles north-west of Odessa. Ted sent Doris three cards from here between the 2nd February and 14th April, 1917. His censored messages are cheerful but reveal little beyond his difficulties with the post.

Locker Lampson arrived at Tiraspol on the 15th January, miffed at having missed the fighting, and the medals lavishly awarded by the Russians. His mission had been largely unsuccessful, though the Division did receive some excellent Model ‘T’ Fords, modified at the Newport workshops. On the 10th February, he left for St. Petersbourg (renamed Petrograd in 1914), to ask the Russian War Ministry for new equipment, and was overtaken there by the revolutionary events that deposed the Tsar.

End of Part Two.

Part 3

As an observer, the gadfly Locker Lampson was suddenly important to the Admiralty. His despatches told of power flowing to Workers' and Soldiers' Committees (Soviets), and collapsing discipline in the Army. Even so, Stavka was planning a Summer offensive in Austrian Galicia (now south-west Poland), where General Brusilov had won a great but costly victory the year before. Alexander Kerensky, Minister of War in the Provisional Government, was quick to reward his British allies with new Fiat armoured cars.

|

Some of the photographs from Ted's collection from his time in the RNAS

|

|

|

|

On the road

|

Model T Ford

|

|

|

|

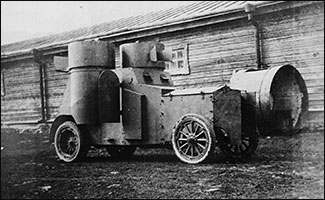

Fiat Armoured Vehicle

|

another armoured vehicle

|

In June, the Division moved to Galicia, and a new forward base at Korsova near the Russian 41st Corps. Kerensky strove to enthuse his frontline troops with passionate speeches, but to no avail. Some units fought well, including the aptly named 'Battalions of Death', one of them all-female, but many refused to leave the trenches or turned on their officers. They were now facing German troops, and German agents were fostering revolution to force Russia out of the war. The veteran revolutionary, V. I. Ulyanov (Lenin), had been brought back from exile in Switzerland for this purpose.

The offensive was a disastrous failure. In July, Kerensky became Prime Minister and belatedly took action against the Bolsheviks, the majority revolutionaries, who had helped to wreck it. Trotsky was imprisoned and Lenin went into hiding. Only one of Ted's cards dates from these momentous times. It was sent to his father by his friend Jim Cox, who wrote from Petrograd on the 3rd July to say that, 'Teddy and myself are both keeping fit. I have not seen Ted for some time, but I know he is quite well.' The Division staffed a small office in Petrograd. The end-game was at hand. General Brusilov, the able Commander-in-Chief, who had advised against the offensive, was sacked and replaced by the reactionary Kornilov.

Advance turned into retreat, but the R.N.A.S. squadrons continued to perform all that was asked of them, plugging gaps in the line left by panicking Russian units. Ted is believed to have served with No.2 Squadron, which, with No.3, 'caused great execution' (a favourite phrase of Locker Lampson's) among the enemy infantry. When some stability was regained, Kornilov sent the British his 'sincere and heartfelt thanks' and a hatful of medals for their 'brave officers and men'.

Among the latter, sympathy for the revolutionaries' cause had waned, though they could not afford to take sides. Sir George Buchanan, the British Ambassador, had already decided it was time for his countrymen to go, and throughout the Summer they were steadily withdrawn, using home leave as a pretext.

Kerensky was adopting a Tsarist demeanour: he had postcards distributed, showing himself in heroic poses. Kornilov, who despised him, was plotting counter-revolution. In September, Kornilov attempted a march on Petrograd; the Soviets armed thousands of citizens, including Bolsheviks, to meet it. The plot failed and Kornilov was arrested. Kerensky took over as Commander-in-Chief but was toppled by the Bolsheviks in November. Civil war would soon follow.

|

|

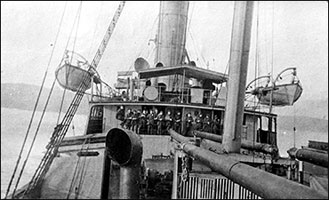

October 1917 Some of the men on the SS Benvenue

on their way back to Britain

|

By now, most of the Division had left Russia, via Archangel and ship to England. Their cars had been sent to winter quarters at Kursk, scene of World War Two's greatest tank battle, in the care of a small maintenance party. This was withdrawn in January, 1918 when relations with the local Soviet turned hostile. A hazardous, two-week train journey took them to Murmansk, where they were almost turned back by order of Trotsky, the new Minister for Foreign Affairs. Curbing the movement of foreign troops was a German condition of the peace treaty being negotiated by Lenin at Brest Litovsk. But Trotsky's tardy message did not prevent the R.N.A.S. rearguard from reaching sanctuary aboard the old battleship 'Glory' and a safe passage home.

In their absence, the Division had been taken over by the Army, becoming a Brigade of the Motor Machine-Gun Corps. Stationed at Belton Camp, near Grantham, where they received equivalent army ranks, the men were preparing to return to Russia for their strangest adventure yet.

The Treaty of Brest Litovsk obliged Russia to cede areas of Trans-Caucasia to Turkey, and with the collapse of General Yudenich's army, it was feared the Turks might move into North Persia, cutting off Britain's oil supplies, or even seize Baku, Russia's oil centre on the Caspian Sea.

An Indian Army officer, Major-General Lionel Dunsterville, a schoolmate of Rudyard Kipling (he was 'Stalky' of 'Stalky & Co.'), was chosen to lead 'Dunsterforce' and frustrate Turkish ambitions. Designated 'Duncars', the new Brigade would be a part of it. Duncar's destination was Mesopotamia, the land between the rivers' (Tigris and Euphrates), now called Iraq. From Basra, they would proceed by barge up the Tigris to Baghdad, captured from the Turks in 1917, and join Dunsterforce. Ill health prevented Locker Lampson from leading them, but he wrote personally to thank everyone who had served with him in Russia.On the 28th January, 1918, the Brigade, commanded by Lt. Col. Smiles, sailed from Southampton for Cherbourg. The first leg of their journey lay through France and Italy, to the port of Taranto. Ted's last postcards to Doris date from this time.

2nd February, '18. A French photoprint of a British officers' mess, in a Nissen hut: 'Dearest Jim, Still going well. Have just arrived at the 2nd rest camp for some grub and a wash. Am still somewhere in France, expect to carry on tonight. By the way, when I left home for Grantham, I rode up to London with Jack Harrison. He's here with the party, there is a big crowd of us all told. Best love and kisses, Yours, Phyllis.'

8th February, '18. A coloured view of the 'Greek Cathedral in the Basilica', location unknown: 'Somewhere in Italy. My dear Jim, still going well and having a good time. Jack and I are together so far. Have just arrived at another rest camp. This is a most beautiful country. Best love to all at home. Ever your's, Phyl.'

Ted's friend Jack had been awarded the Russian St. George Medal for 'Bravery under Fire' at Topalul, Rumania, on the 30th November, 1916.

Excepting these postcards, his photographs are our only record of Ted's part in the confused Dunsterforce affair. The Brigade reached Basra on the 1st March, but their cars, improved, twin-turret Fiats, didn't arrive until April. The Turks had chosen the Baku option, and General Dunsterville planned to advance on the Caspian port of Enzeli (Anzali) to forestall them.

In between, lay 400 miles of rough, mountainous country, sewn with rushing torrents to ford, narrow defiles, and precipitous passes up to 6000 feet. Even so, a squadron and some motor machine-gun sections got through.

By comparison with the ethnic complexities of the campaign, the physical obstacles must have seemed straightforward. Russia's civil war distorted everything, as 'Red' armies clashed with 'White' and former allies intervened against the Bolsheviks to secure their own interests. Added to this were minority peoples with axes to grind. Identifying allies and enemies could be difficult: the Turks employed Persian Jangalis, Kurds and Moslem levies, whilst Dunsterforce joined with Armenians, and both Cossacks and Bolsheviks, when the two were not fighting each other.

Enzeli was saved, but Baku came under siege by superior Turkish forces and had to be evacuated in September. Dunsterforce was disbanded, having succeeded insofar as it had prevented any Russian oil reaching the enemy before the November armistice ended hostilities.

Duncars made a leisurely return to Baghdad. In mid-January, 1919, they embarked for home, travelling by their outward route to arrive at Southampton on the 28th February. They went straight to Belton Park Camp, which had acquired a bad reputation. The unit had suffered its worst casualties to date in the recent battles and, shamefully, six more men died of pneumonia at Belton after having to sleep rough in their thin, tropical uniforms. Many more suffered frostbite in the bitter cold.

Following this scandal, the War Office approved an immediate release for the survivors, who were also allowed to wear their Russian decorations. On the 14th March, in a blizzard, most of them left Grantham station for home. It was, perhaps, an appropriate ending for a unique British force, whose operations have a peculiar resonance in our own times.

Ted Lockie died in 1966, too soon to add his contribution to the Perrett and Lord book. The official papers they used in their research were released in 1968. Ted's best photographs, enhanced and enlarged, are now in the care of the Imperial War Museum (if only they had been postcards!), and two vintage Lanchester cars, highlights of the Lockie sale, have found new owners. I think he would have approved.

|

It was a Lanchester Saloon like this that his son Ted was restoring at the time of his death. |

|

THE END.

|