|

|

||||||||

| By Jean Hunt (nee Ashton), transcribed by Donna Aitken, 2007 | ||||||||

|

Memories of Working Life Dubilier Condenser Co. 1945-6 |

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

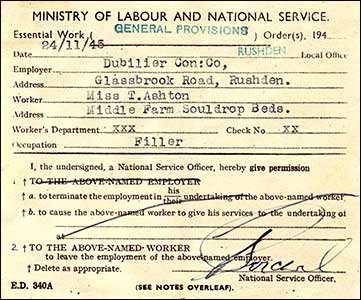

Dubiliers came to Rushden early on in the Second World War, taking over what I think was a boot and shoe factory and they also built onto it. The factory ran along behind the houses in

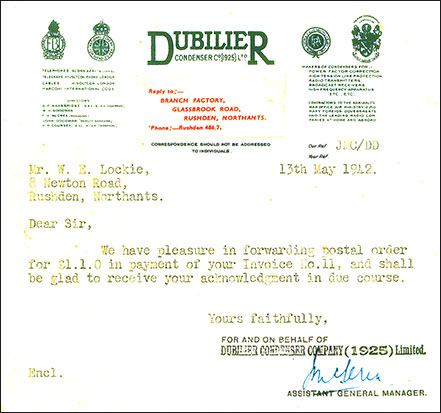

The factory had large slide around doors at the entrance for the workers and a loading bay halfway along between houses. Now in 2007 there is still a factory at the Windmill Club end while the loading bay has become a road entrance to more housing at the back where the rest of the factory used to be. In this tunnel like entrance were the racks that held the cards that each of the workers had their name and address and works number printed on. These cards had to be placed into the clocking machines to have the time stamped on when we went in and out of the factory. A Mr. Gardener would be guarding all from his little windowed office! At the back end were coat racks. We then went through another sliding door into the factory itself. This must also have been the way all the machinery was brought in. Above the entrance hall was the winding room where layers of tissue paper and foil were made into different sized tight rolls with wires through the centres and out the other end – Condensers. The Windmill Club end of the factory was what we girls called the machine shop. Engineering room was the term I suppose we should have used, but what exactly they engineered I have no idea. I just remember it was very noisy. This was the only part that was bricked off, the rest was all open plan. On the odd occasion I did go in to fetch blocks of wax that were stored there, I was just glad that I did not have to work in there and was always so happy to get back through more double doors. I did know one of our village girls who worked in it but we were trained not to ask what went on that did not concern us. What you did not know, you could not talk about. 'Even walls have ears!' we were told. A few men who were exempt from National Service because of the work they did or were too old and a few underage lads worked in there. Next was the room that I worked in, the Condenser room. My first job was melting thin rods of solder, pointed eye level on a gas heated iron and lining eyelet holes in the centre of rubber discs that became tops and bottoms of aluminium cases that in turn became condensers for radios. After the centres made in the winding room had been immersed in boiling Vaseline, they were brought into this room, where each one was tested to see that electric waves would pass through up to a certain voltage. My Cousin Grace White (nee Mole) did this job along with another girl. Next they were threaded by their wires into thin aluminium cases that had rubber discs as a seal at the bottom. Ah now! Were these cases made in the machine room? After I had been 'promoted' they were delivered to the bench I worked on in box-like metal trays with a condenser already threaded in. Order tickets with size and amount required and whether Army, Navy or RAF listed were attached. My job now, was to fill each case with boiling wax and push the top rubber seal down to contain in. I did this job for the rest of the duration. I had a container at eye level, electrically heated that I had to keep filled with blocks of wax that melted and an outlet nozzle operated by my foot allowed the correct amount out to fill the containers. I had to wear very thick leather gloves to hold them in my left hand because the wax was boiling. The rubber discs were baked in a small electric oven to my right and one had to be threaded onto the top wire and pinched home to contain the wax. The girl next to me, Jean Wilby had to clean off any spillage from the outside before it cooled and set. The following girl, Nellie who came from This same operation was done to larger containers that were held in wooden racks as they had to be filled with boiling pitch. It could be dangerous as we could not avoid wax splashes on our arms. It had to set before removal from the skin and it left marks where it had been. The pitch was another matter. I saw one girl knock a filled rack over her arm, I can still hear her screams. She had a badly burned arm and was off work for ages. At least our wax was only spots and cooled quickly and one got used to it. We all had to wear caps on our heads that had nets 'snoods' attached to contain our long hair. These were provided for us. Also, we in our room all wore short sleeved overall/smocks. We were issued with extra clothing coupons so as to be able to buy them without using our Government Issue coupons. Like food at that time, clothes were also in short supply and had to be rationed. There were rows of benches that we worked at with a wide aisle across the centre. What a lot of the people worked at I cannot remember, but there were over a hundred of us in our room alone. Next down this open plan were some electrical objects, kept in padlocked wire cages. Transformers, I would think, but we did not know of those sorts of things at the time. Sometimes, blue flashes came from them and sparks. We were sure that one day they would blow up! Only men who appeared from time to time in white smocks and carrying clipboards ever went inside. The huge vats where the condensers were immersed in boiling Vaseline were next in line. Three or four men worked here. The walkway now became a 'T' junction. This was the mica room and the far end of the factory. My friend from Souldrop village, Nesta Edwards worked there, sorting mica all day long. The shapes had been cut out on jigsaw machines and I presume that all the waste had to be sorted out from them. At the other side of the room something was done with the shapes. We passed through this room to get to the canteen that was up some concrete stairs and at the front again. The offices were up there too. We had a tea break mid morning and afternoon. Just time for a cup of tea after we had dashed through the factory, up the stairs and queued up for it. At mid-day a meal was also prepared and served up for those who wanted it. It cost one shilling (5p). A great many of us had it as we lived a distance off. Also if we ate there it helped with the rationed food at home. After our meal we’d go for a walk out in the town, Nesta and I. No food was allowed on the factory floor, to avoid contamination. One day the other Jean brought an orange in. Fruit was an unheard of luxury. Only children had an odd orange now and then. Jean was proudly showing it to us when the foreman appeared, so she quickly tossed it in the oven out of sight. I turned the oven off. The foreman switched it on, and then he just stood there eyeing us up and down as he suspected something was going on. We expected that at any minute the orange would explode. Running out of cooked buttons I pretended I needed more wax for my pot as I dare not open the oven door. I did not know what to do with the hot wax when I got back as my pot was more or less full, so I tried to stand between it and him so he could not see I was not really putting any in. Then our luck was in, he was called to the phone! Have you tried baked orange? At the far end of the factory was a medical section with two nurses always on duty to cope with minor accidents like the boiling pitch etc, or illness. Girls who came from afar were billeted in wooden army type huts at an encampment at Chimney Corner, Of course there were a lot of Rushden girls and many like myself from surrounding villages. I caught a service bus each day at 7am and another home at 6pm. These buses were diverted via My foreman was a Mr. Roughton, but under his command there was a charge hand for each section. Mine was Audrey Truett. Each day 'Music while you Work' was broadcast by the BBC radio mid-morning and afternoon and relayed by speakers to us. We all sang along to it. These speakers were also used for messages, like fire drill, our turn for the canteen, air raid etc. Don’t think we had any real ones of those! All those old enough, me not being fifty, had to do nights on fire-watching, in case of incendiary bombs being dropped on us. The factory did not work nights. The radio components that we were making were for all branches of the armed services. I was always pleased to see 'Royal Navy' on the order chits as my boyfriend whom I was later to marry was a sailor and I felt I was helping him. One of our bosses was awarded the MBE. We had placards up with 'Make/Made Best Effort' on them. After getting used to working indoors, I had some pleasant times at Dubiliers. As the only two ways of leaving anyway was by joining up or getting pregnant you just had to make the best of it and get on with the job in hand. After the war the firm returned to its original base in

|

||||||||