|

||||||

| From an interview by Rae Drage on 29.9.2008. Transcribed by Jacky Lawrence |

||||||

|

John Lewis - Electric Company Worker

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

I first came to Rushden to work from Podington, used to bike there until I was what fifteen then I moved to Rushden with my parents. [c1933] I was in Rushden for a year and my dad was killed down the bottom of Wellingborough Road when the floor of the grainery collapsed at Clark’s Farm, opposite St. Peter’s Avenue. That left me with the responsibility of looking after my mum, she was blind so it was mum and me. I had to change my job, I went to work for Marriott’s for a short while then the winter came, we were stood off. I was on the dole for a short while and I was allowed nine shillings a week for my mum and me to live on. Well I had to get a job where I could get some money so I worked for the railway for a while. Then I had an accident there and they found out I was too young. I did get crushed in one of the carriages when we were unloading it. This heavy thing fell across my chest, so that’s when they found out I was too young to be there. I was on the dole for about a fortnight, in those days if you were offered a job you had to take it, you weren’t allowed to say no. They found a job for me at one of the butchers’ shops in the High Street. I didn’t want to go so a friend of mine said. ‘Well go along to the Electricity Board they want men.’ So I went to see the engineer and the lady in the office said. ‘I’m sorry he’s not here but could I have your name and address.’ I gave her my name and address and I went down to the butcher’s shop and said. ‘I’ll be here after lunch.’ I went home to tell mum then, there was a letter left behind at home for me to start work immediately so I started work that morning at 12 o’clock up the top of St. Margaret’s Avenue and I stayed on the company until I retired at 65. I started off first as a labourer but I wasn’t a labourer for long because the engineer had a word with me he said. ‘Well you’re young ,you’re active I’d like you to stay with us.’ I mean that was the first day so he must have liked the look of me, mustn’t he. He said, ‘Leave the digging you’re doing and go and work with the jointer.’ Now the jointer was the man who laid the electrics and connected every house up, put all the mains in and all that sort of thing. I stayed with him for a while and then I was moved to the overhead section and that entailed me going all round the area with the rest of the men. Labourers, jointers, linesmen, putting electrics into villages which of course in those days, I’m going back to 1936, half the villages, in fact quite a lot of them, Rushden, didn’t have electric they were all on gas.

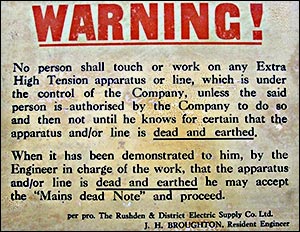

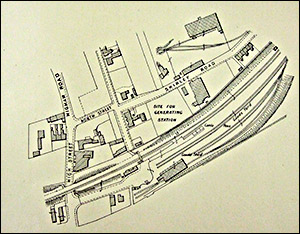

In the end I was made a jointer’s mate that meant I had to dig the holes for him and make sure that everything was ready. The blow lamps were blowing, everything was hot and then eventually I was moved up to the high volt jointer and he was known as the gentleman jointer. The way he used to dress you wouldn’t think he was going to work on dirty work ,well it was muddy at times, he was always dressed up in a black suit and stiff collar and tie and he was to look at and to behave, he was the son of a gentleman you could tell but he’d come across hard times. I stayed with him until the war started and then I went into the Army. I went into the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. Well they wanted to know what job I was doing and as I worked on electric they wouldn’t let me go in the Infantry. I wanted to go in the Royal Engineers they said, no with your capabilities we’ll put you in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. That was the corps that supplied all the heavy guns, small guns, light, big guns, everything to the Infantry. I went down south into Wiltshire to be with the Yates Army Field Repair Workshop outfit. Then I had to go to Woolwich to the Royal College of Science and Technology for technical training when things were getting a little bit complicated. We had to know all the electrics and all the fancy stuff. I passed out there and was transferred to a part of London that was getting heavily bombed to be trained as a fitter as well as being an electrician. Most of the time there we spent getting bodies out of damaged buildings, that wasn’t very nice actually. Anyway I finished my course there and I was moved to the main depot in the country in the Midlands and that was bombed the next day. I was only there three weeks and I was sent to Scotland because that was being bombed as well. For a long time I was there as an electrician keeping the electrical side of the guns, the big guns, they were in groups of four and all their equipment was fancy work. We even had computers, now computers weren’t heard of in those days. We had computers that worked out where the German planes were, the height everything like that. The guns had got massive batteries and they used to push the power, it was a part built onto the gun that ran the shell which weighed eighty five pounds up the barrel and that was a massive battery that used to weigh four hundred weight and that was electrical of course, so we had to keep that in running order. We had to keep all the electrics in running order, we even had radar then and that was completely unheard of but that again needed its maintenance. I stayed up in Scotland for three years and by that time we were beginning to win the war so I was sent away to another place, near Edinburgh, for another technical training on new equipment coming out and almost immediately transferred to the Tank Corps down in Dorset. Earlier on I’d been to Birmingham, to Rolls Royce’s, Morris Motors and one other big firm, Lucas, and that I suppose was in my records. I was sent then to the Armoured Corps at Bovington that’s where we maintained the tanks and I stayed there for a year or more I suppose. I was promoted by then to a corporal, I was being promoted gently by the way. From then onwards the invasion of Europe was about to start so I was transferred up to Yorkshire so we were near the coast. It was quite a big area, we got literally thousands of armoured vehicles and as the troops went through to the docks they brought their old tackle in and we equipped them with new ones. Tanks, Bren gun carriers and all sorts of things like that so when that was over and the war was going on alright in France and so forth I was replaced by somebody else and I was going on leave no, not on leave, I was going abroad. I was transferred to Nottingham, I was there for a fortnight and then at the last minute, all ready to go and they said. ‘Oh you’re due to be demobbed soon, you’re a low demob number so we’re not sending you. You were a replacement so you stop here and in the next draft we’ll expect you to march the men up from the station to form the next lot to go over.’ Anyway the next draft come in and I should have gone with it but I didn’t. So I went to see the Commander and I asked him what was going on. ’Well,’ he says, ‘ You’re such a low demob number that you don’t want to go do you?’ I said. ‘Yes I do, I’ve been around this country quite a bit if there’s a chance that I can go let me go.’ He was ever such a nice officer he was. He mentioned India, I said. ‘I’ll go to India then.’ So I went to India. I should have been there for many weeks really but I was there for a year. After I’d done a year I came back to England and finished up at Northampton Racecourse then we were demobbed and I came home. I had three months leave then I went back to the company and within a few months I was promoted to the staff which entitled me to proper holidays and a pension. So, quite a good pension enough to keep me going, sort of thing. I was trained as a high voltage jointer, that means I could tackle up to 11,000 volts, well 33,000 as well actually and I stayed doing that until I retired about 1982. Rushden originally, I think it was talked about being electrified in the late eighteen hundreds, about 1895. Stopford Sackville, he’d got a big house, Drayton House at Lowick. Robert Marriott he was one, the old original Robert Marriott. There was Peck who used to be the transport people, there was Corby who had a tannery down John Street and Clark who used to have the factory in Midland Road, Jaques and Clark. They were the main five directors and it was their money that put Rushden electric on the electric supply. They started it about 1896 I think, something like that.

That was done I should think in, must have been in 1920/26 time. Then Rushden Electric Supply Company supplied electric to Thrapston and Oundle and all the villages in between and back this way to Sharnbrook and Harrold and all the villages in that area. But then we were nationalised so then we were taken over by Wellingborough and then Wellingborough and Rushden were taken over by Kettering and by that time I’d left. People never realised that Rushden was so important but we supplied right out to Oundle. There we supplied Oundle School and the brewery and everything and there was this estate here it was one of my jobs, I laid the cables here and I connected every house here. I did them at Oundle, I did them at Thrapston, I was a right busy man. These were built the end of the war, do you know who made the roads? German prisoners, they did the roads, Wellingborough Company did the paths and Drabble built the houses and the houses are prefabricated. First of all they were built with a frame, like a Meccano almost. Then there were a four and a half inch brick wall outside and then the lamination was brick wall, the insulation steel insulation and the wall is only half an inch thick that was reinforced plasterboard. |

||||||