|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ivy Boot Works

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Rise and Advance of the 1892-1950 By W. Henry Brown

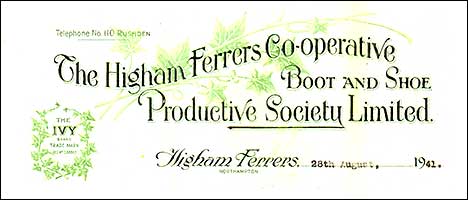

Greetings of the Committee to IN THE TWILIGHT of the waning 19th century when machinery was transforming the footwear industry from the homes of the operatives to the factories of the capitalists, some of the co-operators and trade unionists in Northamptonshire sought the application of the co-operative principle in the establishment of works in which those who made the boots and shoes should be associated with those who wore them—an equitable relationship. Higham Ferrers had been long associated with the leather trade and the manufacture of boots and shoes and some of the ardent co-operators in the ancient borough decided, in 1892, to venture on the establishment of a boot and shoe factory. Encouraged by the share capital and promised support of distributive societies favouring co-operative production the Higham Ferrers Co-operative Boot and Shoe Productive Society Ltd. was registered and in 1894 the first despatch of orders from the Ivy Works proved the foundation of success. We had intended that the Jubilee of the Society should have been the occasion of much rejoicing in the county; but the War was raging. Many of the men were in the Forces; and those who remained were making boots for those on the march to victory. Now that the British people are looking forward to the Festival of Britain in 1951 and the International Co-operative Alliance is calling the world to the peaceful penetration of its regard for human rights we, in Higham Ferrers which was first created a borough in 1251 are proud to record our history on the eve of the national celebration of great events. Happily the author who first came our way with Holyoake, Blandford, Greening and the veterans of operation, nearly fifty years ago, has been able to add the story of the Ivy works to his histories of the Rochdale Pioneers and the societies of London, Brighton, Liverpool, Bath, Cambridge, Sheerness and a score of others that recognise the co-operative principle of production in their distributive service. He has known our struggles in the past and has witnessed our success in the present. And we the committee elected by the members, look forward to the support of the readers in carrying the good work well forward in the future. We have the confidence of the men and women in the factory at Higham Ferrers with its kindred branch at Blackburn, and we trust those who read its history will walk in the "Ivy" shoes and boots that will carry them along the co-operative highway. Yours fraternally,

Where the "Ivy" Clings Now that the industrial outposts of the Workshop of the World—as Britain was designated in the mid-Victorian Era—are seeking new avenues for housing their crowded populations it is well to glance at some of the smaller communities that are expanding their manufacturing facilities in the valleys and woodlands of the countryside. Within seventy miles of London is a little borough which in 1066—a year that every schoolboy is told to remember—William the Conqueror regarded as a choice spot in the Land of Hope and Glory. He entrusted its oversight to one of his valiant vassals, William Peverill, the remains of whose moated castle now shadow the hilltop. Peverill was succeeded by William de Ferrers. He freed the serfs who cultivated the land and thus gave them the opportunity of sharing the harvest. They found more pleasure in working together and helping one another than in standing alone. Since then the borough of Higham Ferrers has steered through the plagues and panics of the Middle Ages and is now advancing on its own footwear to "Better Business : Better Living" as the late Sir Horace Plunkett regarded Co-operation. Higham Ferrers was created a seignorial borough in 1251. In the 15th century one of its sons, Henry Chichele, recognising that knowledge is power, founded a college in his home town and that of All Souls College at Oxford, before becoming Archbishop of Canterbury, 1413-1433. Facing the college in Higham Ferrers— which, in 1948, was handed to the Ministry of Works for preservation as an ancient monument—is Ivy House, erected in 1633, and now in the possession of All Souls College. On the main highway from the town the local authorities have paid tribute to the memory of Henry Chichele by naming the thoroughfare, along which runs one side of the works of the Higham Ferrers Co-operative Boot and Shoe Productive Society Ltd. as Chichele Street. This was in harmony with the society's upholding of "Ivy" as the name of their products which have carried the reputation of Higham Ferrers throughout the British Isles and Overseas. The March of the Machine That there is no new thing under the sun is a truism well established in the public mind. During the World War the oversight of the boot and shoe industry by the State, was a revival of the trade ordinances of the 14th century when the Statute of Edward III counselled bootmakers not to sell footwear in any other manner than that prescribed by their craft guild. In 1378 another statute sought the regulation of wages in equitable relation to maker and wearer. Twenty-four years later those who sold boots on their premises in Northampton had to pay a licence fee of 6s. 8d. to the local authorities. By 1550 the trade was flourishing so abundantly that the fee was raised to 30s. The hamlets round about were thriving on leather. Their menfolk made boots that sold and lasted. Rich grazing lands in the valley of the Nene supplied the hides. Oak bark for their tanning was found in the village woodlands. Thomas Fuller (1608-61) wrote that the town and shire (In the county of Northamptonshire 30,500 men and boys; and 21,600 women and girls are now employed in the production of men's boots and shoes. In addition, many others are engaged in the manufacture of women’s footwear that is now adding to the resources and the reputation of the county.) of "Northampton may be said to stand other men's legs, where, if not the best, the cheapest boots are bought in England." And when the army of the Parliamentary forces marched through Northampton in 1648 they were given 1,500 pairs of boots—proof of the generosity of the disciples of St. Crispin. Bootmaking was a handicraft in that thrilling age. The work was done by "the hands" in their cottage homes and, when finished, taken to "the masters" who supplied the materials to the craftsmen. The employers gained Wealth; their workers endured Want. Then came the Friendly Society of the Cordwainers of England, which, in 1784, sought the welfare of the craftsmen whose employment of apprentices was helping those with large families to stave the younger children from starvation with the meagre earnings of the elder boys. Apprenticeship became a potent factor in the business. When the 19th century dawned the home-workers in the boot and shoe industry became alarmed by new methods and machinery threatening the domestic outlook. Pay was poor; but the men had pride in the family circle where they lived and worked from early morn till dewy eve. In the North of England the working people felt the hardening rush of the Industrial Revolution where the "dark Satanic mills" were shadowing the countryside. The bootmakers in the East Midlands felt the pinch of poverty when the Corn Laws sustained the landed gentry at the expense of the lowly-placed. When the Chartists and the Anti-Corn-Law League arranged a debate between their champions, Feargus O'Connor and Richard Cobden, at Northampton in 1844—the year the Rochdale Pioneers were exploring Toad Lane—the shoemakers had a hopeful gleam. Cobden's plea for the cheapening of the daily bread was re-told in the homely inns and church and chapel rooms in the township of Higham Ferrers and the nearby hamlets. But when prices fell earnings lowered; and the people went on wanting; despite the crumbs of comfort scattered throughout the country when the Corn Laws were repealed. The introduction of a sewing machine for "closing the uppers" awakened the shoemakers from their complacence. Those in the county town determined not to "make up" for any employer who ventured on machine prepared tops. The Boot and Shoe Makers' Mutual Protection Society was formed to help the men who went on strike against the inroads of machinery. Distress spread like the plague that had besmirched the valley of the Nene three centuries before. Shoemakers left their little homesteads and tramped the Midlands in search of work while their families sought parish relief. That dispute continued for a couple of years till "the masters" offered a slight advance in the rates for making up machine made tops. And the men returned from their wandering in the Wilderness of Want to take their earnings in the Truck shops of their masters. For Henry Pitman in The Co-operator revealed how the Truck shops in the hamlets around Higham Ferrers controlled or owned by the employers demanded the custom of their employees. True, the legislature had sought to ease the strain on the housewives; but not till Charles Bradlaugh, M.P. for Northampton, secured the Truck Act of 1887 was it made compulsory that wages should be paid in the coin (now Treasury Notes) of the realm. The Co-operator exposed the way in which boot and shoe makers working in their cottage homes and out-houses were earning 2½d. per hour, most of which had to be spent in the Truck shops of the employers, one of whom sought to justify his greed by explaining that "the question of subsistence upon 2½d. per hour must be entertained with other influences such as competition and the price of material which govern the rate of wages." Such was the economic theory of Private Enterprise in the Victorian Age. Adventurous co-operators in the county had sought a way out of the hazard by starting workshops on a co-operative basis to which shoemaker members could take the products of their home labour. The failure of seven of those societies by 1880 did not dishearten the zealots. Mrs. Sidney Webb (Beatrice Potter) delved into the matter in 1890-1 and found three co-operative boot works in Northamptonshire still dependent on the outworkers. These productive societies employed 363 people, of whom only 27 worked in the three factories; the other 336 operating in their own homes acting as journeymen in carrying their products to their own works. Similar practice prevailed throughout the county. Slowly it faded into the vault of Memory when the majority of the workers agreed to link in the factory circle on the advice of their shrewdly observant trade union. For, in the January of 1893 the National Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives recorded that: "There were a number of workers opposed to leaving their homes to go into the factories but in all such matters the minority must abide by the decision of the majority and it is an incontrovertible fact that the vast majority are in favour of indoor work; and to the minority we would point out that, whether we will or no, indoor work is sure to come by the introduction of machinery ; and those who cling to working at home will soon be left high and dry without any work to do whilst those who agree to go inside will be employed on and with the machine." Thus ended the cottage home Era in the boot and shoe industry. During the last years of the domestic phase of the industry, J. G. Whittier, the Quaker poet of Massachusetts wrote his "Songs of Labour" in which he thus addressed "The Shoemaker":

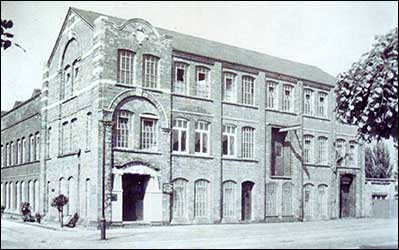

Such message might well apply to those in the footwear industry of Northamptonshire—the most co-operatively-conscious county in the country. Co-operators are naturally counselled to walk on their own feet—in their own co-operative shoes—along the path of peaceful Prosperity where the "Ivy" clings. The last decade of the 19th century when the "Ivy" boot and shoe came upon the co-operative highway from the smallest borough in Northants was a season of social advance. For the British people were implementing the declaration of John Ruskin that "the first duty of a State is to see that every child born therein shall be well housed, clothed, fed and educated till it attains years of discretion." The raising of age for the employment of the kiddies from 9 to 10 years; and giving them free education in the elementary schools in 1891 was a hopeful starting point, coupled with parental regard, for their years of discretion" in the homely old borough of Higham Ferrers. The men had pride in their craftsmanship that gave service to the community and sustained the family unity. The youngsters shared fathers' pleasure as they toddled round the benches where their parents spent the day. When the boys left school they longed to follow in their fathers' footsteps. Such was the mainspring of the family life when the lure of the machine was diverting the homely course. Its swan-song was sung in the twilight of the 'nineties when a protest against the harsh conditions imposed by the employers rallied the workers to united action. Truly 1890 was a hazardous year in and about Higham Ferrers, it darkened as the months glided to the end. Several bankruptcies were recorded in the boot and shoe trade; boy labour was being exploited in some of the factories; and disputes between the War Office and the makers of Army boots became the main topic of family conversation. The refreshing provision in the clubs and the public houses filled the leisure hours when the day's work was done with spirited delight. And when language flowed too fiercely on leaving the friendly inn the publicity accorded to the police court proceedings in the Rushden Echo proved a restraining influence for many a week. Rabbit coursing street corner gambling, and occasional dog fights were outdoor pursuits in Higham Ferrers where 1,500 people lived and toiled most of their years. And of those 1,500 residents 32% were under 15 years of age; only 6% were women and men of over 60 and 65 years old. Now people are living longer and staying younger. The proportion of the elder brethren has more than doubled and that of the youngsters has fallen to less than half the percentage of fifty years ago. Truly the last half century has witnessed the healthy advance of the men who travel on British shoes and boots of which 4 out of every 5 pairs made in Britain come from Northamptonshire. But all was not beer and skittles in Higham Ferrers in the Naughty and Hopeful 'Nineties. There were radiant gleams in the schools, churches and chapels of the borough. The annual supper of the shopkeepers drew a happy company of sixty rival traders. When a merchant opened his new warehouse the event was cele¬brated by "candle-light with a plentiful supply of bread and cheese—ale was also provided"—as duly recorded in the Rushden Echo which also told of a dozen parents being fined 4s. each and costs, at the police court for not sending their children to school. The School Board had a human educational outlook; when it arranged evening cookery classes for the womenfolk to add to the allurements of the home table. And the Higham Ferrers Temperance Society urged men to total abstinence from intoxicants as the tee-total virtue of mankind. Rabbit coursing was a sporting attraction in the district and in the Spring a railway excursion took 350 boot and shoe operatives to the Northampton Races. That summer the Band of Hope excursioned a thousand trippers to Yarmouth; the railway company "kindly provided a saloon for the committee." But as the year went forward the labour outlook went backward. Fortunately the Rushden and District Branch of the National Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives with which Higham Ferrers is linked was on the alert. Discussions between the Army boot contractors and their workmen led to an agreed statement as to wages. Trouble arose when this was repudiated by some of the employers. Thereupon the local branch of the trade union transferred its headquarters from the Railway Inn at Rushden to the Club House in the headquarters of the local trade union authority at Higham Ferrers. There the delegates met and discussed their difficulties. Decision was reached after the Masters had been "weighed in the balance and found wanting"— as Solomon Upton one of the most far-seeing of the workers in the district observed when he urged that they should adhere to the findings of the Arbitration Board which some of the employers resented. In October 1890 a strike was declared and by the second week in November, 5,000 of the operatives in Higham Ferrers, Rushden and Wellingborough had ceased work. At the end of the month the Board of Arbitration came to a decision favourable to the employers; and the men had to return to the factories for the sake of their families in that doleful December. Following the Christmas greetings came omens of a Happier New Year when the local co-operative society opened its store to provision the consumers at the family table. And the people at Raunds and Wellingborough found comfort in similarly co-operating for their daily needs. The three distributive societies thus established in that year of discontent have been sustained in the spirit of the prophet Isaiah for "they helped every one his neighbour and everyone said to his brother be of good courage"—co-operate. In Higham Ferrers the Jubilee celebrations of the Foresters was an occasion of rejoicing. Parents were gladdened when the Sunday Schools and Bands of Hope linked in autumnal festivals of good-will. The men in the factories and the lesser number who clicked on the benches in their homes went on working—urged by Solomon Upton to do some thinking of their future. Their little town had grown slowly and he told them to cultivate it to a better harvest for those who dwelt within its border. Thus he became the missionary for the social salvation of those who soled and heeled so that the working folks should stroll in comfort along life's long road. They talked things over as they walked to the factories. Then they met their neighbours in their cottage homes after the evening meal. In those friendly gatherings they discovered that there was more pleasure in striving together than in standing alone. And one night in December, 1891 half a dozen of those valiant fellows resolved to explore the industrial wilderness to find an oasis in which they and their fellow-workers might rise to calm content in Service above Self. Consumers had enjoyed the security of co¬operation, why should not producers work together in association and thus prove that, as John Ruskin had declared, "Co-operation is the Law of Life"? Before learning their answer to that question we will glance back to the Higham Ferrerians of the 19th century. For, as Lord Byron, the last Lord of the Manor of Rochdale, declared:— "The best of the prophets of the Future is the Past." The Pioneers of "Ivy" Works At the Dawn of the 19th century there were only 726 men, women and children in the few big houses and some small ones in Higham Ferrers. That was in 1801. By 1841 the population increased to 1020. But many of the younger folks were drifting to the towns where machinery was quickening production and adding to the spice, as well as the risks, of life. In 1871 English farming was nearing its prosperous peak with 1255 sturdy people in this pleasant stretch of the Nene valley. They numbered 1468 in 1881. The population had doubled in the eighty years. It more than doubled in the next four decades; and rose to 2930 in 1921. Now there are 3,350 people in the 1,180 houses on the 1945 acres of Higham Ferrers. A third of the houses are owned by the borough council-another instance of the close association of citizens and co-operators in mutual endeavour for the common good. His worship the Mayor is linked in this co-operative circle for he is the working president of the Higham Ferrers Co-operative Boot and Shoe Productive Society Ltd. He is also a member of the management committee of the co-operative society that provisions the towns¬people with good fare. Councillor Solomon Upton is the son of the Solomon Upton who urged the men of Higham Ferrers to work, and think, for themselves when the production of footwear was on the industrial crossword, as revealed by my old friend, Ben Jones, the London manager of the C.W.S., in his volume on "Co-operative Production." [Published by the Clarendon Press at Oxford in 1894] There he wrote that "during the three years 1890-92 the boot trade was very much altered by the almost general adoption of the factory system instead of the old plan of working at home, and by the rapid introduction of machinery." Returning to 1891 the half dozen social explorers—Solomon Upton, Harry Burgess, John Webb, Tom Kent, George Kent and Arthur Pack—met "to consider if it would be advisable to start manufacturing so that we could reap the benefit of our own labour." Fortunately the wisdom of Solomon was manifest in his noting the proceedings on a sheet of paper which is treasured by his family and which records: "The first question we discussed was: Is it beneficial for us to start manufacturing? All were of the opinion that it would be. The second question was the number of members we should want and if it should be confined to Higham. We thought it wise to get all we could in Higham before anywhere else. The final question was whether we should accept foremen in it and the opinion was that we let them remain as they are, and not let them know anything about it." There was a significant tinge in that last decision. These pioneers were operatives. If the foremen knew they were contemplating the establishment of a factory likely to compete with those of the commercial order the news would soon reach the inner circle. Hence the circumspection of the adventurous sextette who "would not let them know anything about it." They wanted to mind their own business in equitable relationship to one another. And on January 26th, 1892 they met again in company with friends whose names are now recorded in the historic annals of Higham Ferrers—J. W. Draper, G. Pashler, W. Litchfield, J. Horsefield, C. Litchfield, F. Clark, and S. Stanley. They resolved themselves into the provisional committee of the new society and elected S. Upton, president; W. Litchfield, secretary; and G. Kent, treasurer. Then they got down to business details and decided to convene a public meeting at the trade union headquarters at the Club House on the 29th, engaging the Town Crier to go through the town the day before announcing the event. And on January 29th, 1892, the Higham Ferrers Co-operative Boot and Shoe Productive Society Ltd. was launched with the thirteen ardent fellows already mentioned to steer it to a haven of content. Descendants of that constructive force have followed their fathers' footsteps along the Kimbolton Road where the co-operative shoe works give industrial distinction to the leafy glades of the main highway. Solomon Upton was president till his death in 1920 when the dwellers in the town, as well as the workers in the factory, mourned the loss of a faithful friend. The election of his son, Solomon Upton, Junior, to the committee in 1919 continued the family tradition and his presidency since 1935 has sustained the foresight of his forbear. And as the foreman clicker in the "Ivy" works where he began as boy in the 1890's he sees the uppers are right. The present members of the committee include Mr. L. W. Burgess, a grandson of Harry Burgess and Mr. A. G. Pack, the son of Arthur Pack. Another son of the last named pioneer, Mr. J. C. Pack is now the foreman in the Bottom Stock department of the works. Prior to the recent World War his brother was "on the road" for the society's productions and now a nephew, Mr. F. A. R. Pack is travelling on the "Ivy" road with 16 years of ardent service to his credit. Mr. C. Richardson, another member of the present committee, is the son of Mr. Walter Richardson, who joined with the pioneers at the inaugural meeting in 1892 and whose twilight years are brightened with the success of the society he nursed in its fledgling morn. Mention has been made of two of the workers who began service with the society when it began in Wood Street. There is another, Mr. Owen Martin, who, in the clicking room, proves his skilful competence. Managers of the retail societies throughout Great Britain welcome the representatives of the shoe factory at Higham Ferrers as the seasons of the year come and go. Mr. F. A. R. Pack ranges on the eastern side of the English homeland from the Straits of Dover to Hadrian's Wall. On the western area from the Lakeland to the Cornish coast the business insight of Mr. F. C. Ashby is at the service of the co-operative stores, including those of the Principality of Wales. And Messrs. Pack and Ashby share in the goodwill of the Midlands. Over the Border of the Tweed, Mr. W. D. Jamieson (whose father is the boot and shoe manager of the Dunfermline society) is linking the "Ivy" brand of footwear with the progress of the Scottish societies. Thus the whole of Great Britain has its footing in the valley of the Nene. Mr. F. C. Ashby from his youth upwards studied every aspect of footwear in the leading factories of the county. In 1939 he responded to the national call and, joining the R.A.O.C., followed Lord Wavell through the desert and rendered valiant service in Greece and the East. When the war was over he returned to his Northamptonshire and, since 1945, has represented the society "on the road" of "Ivy" ease and comfort. Thus the co-operative trading missionaries sustain the tradition of St. Crispin and their forbears in good endeavour for the ancient borough. Co-operative buyers should avail themselves of the services of these representatives of the Higham Ferrers factory in securing ample supplies of seasonal as well as fashionable shoes to ensure the comfort and content of the loyal members of their societies. The designers and the makers in the "Ivy" works are modern in their outlook and output. And the travellers are far-seeing as to prospects of the future. They link the sellers and the wearers in a circle of co-operative understanding. Early Associations In a little workshop (now demolished) behind the Town Hall in the Market Place of Higham Ferrers the society commenced productive operations in 1894 with a capital of just over £300. Sales averaged £40 a week during the year when "gents' boots from 5s. 11d. to 17s. 6d." were sold in the footwear departments of co-operative societies. They doubled to £4,377 in 1896 and, in the Jubilee year of Queen Victoria (1897) a profit of £120 gratified both the makers and wearers of the "Ivy" boots. Departmental managers of the distributive societies responded to the call for orders—and those societies that thus encouraged the co-operative venture have continued their support in Peace and (as far as Government contracts allowed) in War. Reverting to 1894 one recalls the opening of a London depot (in Southampton Row) by Thomas Blandford, the secretary of the Co-operative Productive Federation, for the display of the productions of the societies linked in that associative effort. There he interested trade unionists and co-operators in their equitable relationship and created a market for the newly fledged productive societies, of which there were a score in the boot and shoe trade with an aggregate output of £166,000 in 1897. Blandford's selfless service for the struggling ventures found full vent in organising the exhibition of their productions at the National Co-operative Festivals which E. O. Greening had instituted at the Crystal Palace; and to which Mr. T. Ekins (Mr. Ekins began his life's work in the old factory in Wood Street and retired from that in the Kimbolton Road a few years ago) conveyed specimens from the "Ivy" works. There, with Joseph Greenwood (Hebden Bridge) J. Lambert (Bradford) G. Newell (Leicester) and other workers in the co-operative factories he demonstrated the merits of the Power that comes from Knowledge and Unity of Purpose. Blandford's kindly counsel helped them in obtaining co-operative capital and custom. He fostered the societies in generous amiability and democratic development; and, when he passed on in 1899, the Co-operative Union instituted the Blandford Congress Memorial Fund which annually reminds co-operators of one who helped to make their foundation sure. Steadily the "Ivy" works went forward. In 1896 the Royal Arsenal (Woolwich) and Stratford (now London) societies made effective displays of its productions and its trade mark became familiar in the Metropolitan area where it has never lost its savour. Conferences at Mansfield House and other University Settlements were addressed by Henry Vivian, H. J. May, E. O. Greening, and other eminent co-operators who enthused the educationalists to co-operative understanding—on boots and shoes of co-operative origin in accordance with the teaching of Solomon of Higham Ferrers. And when, in 1899, Robert Halstead came from Hebden Bridge to carry on the persuasive mission of Blandford and uphold the Federation at Leicester the workers in the ''Ivy" factory welcomed him for associative relations. The society was well on the way to progress. In 1898, Mr. F. Walker whose business capacity was coupled with co-operative principle became secretary. His devotion to its service till his resignation in 1917 helped it forward to greater strides. Mr. Walker, whose home is in the Kimbolton Road, next to the shoe works, was given the Freedom of the Borough in 1947; and his public services on the Council and on the old School Board are a treasured memory of the citizens. By 1902 the share capital was well over £1,000 and in 1904 the trade was reckoned in five figures. Business was advancing beyond the capacity of the works. Like Milton the committee were anxious to "direct the clasping ivy where to climb" and determined to quit the region of the Town Hall and Market Place. They bought land on the Kimbolton Road and the erection of a large factory and its equipment with the most modern machinery in 1904 hastened progress. With such a pleasing prospect the society presented the Borough Council with an avenue of lime trees along the highway giving a naturally fine approach to the town. Between 1904 and 1913 the annual sales doubled to well over £21,000 and the members of the staff spent most of their Christmas holiday in overhauling the office and the various departments of the works to start the New Year under the most favourable conditions. Then about 800 square yards of land facing the Chichele street behind the works were acquired for further development, orders were plentiful and the operatives were busy, feeling—as William Morris once wrote, that: "the pleasurable exercise of our energies is the source of all art and the cause of all happiness."

Alas! In the autumn of 1914 came an omen of the coming strife, he society received a contract for the British Army and, at the request of the War Office, the Higham Ferrers Co-operative Boot and Shoe Productive Society Ltd. tendered successfully for the supply of boots for the Italian Army. British troops were marching to battle. Men were going from the factory to the Forces. The committee were equally quick in action. They joined with other local associations in organising the Home Front for national and neighbourly service. With the distributive society they rallied the residents to social gatherings to lessen the gloom of the dismal evenings. Men from the "Ivy" factory were cheered on the battlefields by letters and good fare from their colleagues and gladdened by the parcels from the committee during those desperate years. In 1916 under the Defence of the Realm Order the War Office commanded the society to devote the greater part of its output to the production of boots for the British, Italian and Russian armies; long boots for the Cossacks; trench boots for the British troops. The War Office requisitioned three-fourths of the production of the "Ivy" works for the British and Allied Forces. Later when all the men of military age had joined the Forces there was difficulty in keeping the various departments evenly balanced for such rapid production. But all who were left at home worked well together—till the troops were rightly shod—for victory. The economic depression following the 1914-18 War slackened employment throughout the land for many a year. Boot repairers were wanted instead of bootmakers. Despite such disturbing elements the society retained the confidence of the distributors by restraining prices so that customers could be fitted according to their slender resources in accordance with the maxim of "All for Each and Each for All." Testimony to the regard of the society for the makers and wearers of "Ivy" boots as trade unionists and co-operators has been accorded by the M.P.s. residing in, and representing, Higham Ferrers at Westminster. Mr. A. C. Allen, M.P. past president of the Higham Ferrers and Rushden Branch of the National Boot and Shoe Operatives' Union lives in the "Ivy" region while serving Market Bosworth in the House of Commons as Parliamentary Secretary to the Chancellor of the Exchequer. There Mr. G. S. Lindgren, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Town and Country Planning sits for the Wellingborough Division which includes Higham Ferrers. Thus Democracy keeps in step on the road to Progress. Pride and Enterprise When, on a cold wintry evening in November, 1949, I was warmly welcomed by the committee in the canteen of the "Ivy" works, memory recalled a similar gathering in Kettering 46 years before. Thither I travelled with G. J. Holyoake for a co-operative festival where the great advocate of Co-operation declared that the co-operative principle sought to enlist the pride, the affection, the intelligence and the enterprise of the workers—men and women. Something of that spirit was evidenced in Higham Ferrers in 1934 when, in the industrial depression throughout the country the boot and shoe trade was down at heel. During the 1914-18 War production rose and reached a record height in the boom of 1919-20. In the latter year the sales from the "Ivy" factory trebled those of a decade before. Then came the slump and the output of the society halved in 1921. Profits lessened and, in 1930, disappeared. Happily reserves had been strengthened in the prosperous seasons so that shareholding societies and members received their interest according to rule. But the trading dilemma continued to dull the outlook. In the economic crisis of 1931 the percentage of unemployed workers in the boot and shoe industry was 11.5. All the factories, in and near the valley of the Nene, felt the stress and strain in the early Thirties of the Nineteen Hundreds. Not only was short-time in the works occasioning general concern but machinery was still making headway over manual labour. While the production of boots and shoes in the whole of the factories in Great Britain in 1935 was 11.5% higher than in 1924, the percentage of insured workers employed in the industry lessened by 5.5%. During the summer of 1934 the operatives in the "Ivy" factory worked—and worried when there was a loss of £90, after interest on capital and the depreciation of buildings and plant had been provided for. But they laboured untiringly with the intelligent enterprise that Holyoake had extolled, and hoped for a gleam of security in that clouded season. And the committee cogitated with courageous confidence in their co-operative policy of "Each for All and All for Each." In such a dolorous atmosphere (Unemployment between the two Wars lessened the demand for boots shoes and stemmed production in the factories. Early in 1921 there were 1,664,000 registered "unemployed" at the Labour Exchanges; and "down-and-outs" numbered 2,000,000 by the end of the year. They hardly ever fell below a million till 1939 when, in the January before the World War, they rose to 2,000,000—a sad New Year Greeting) Mr. C. S. Ashby, who had an authoritative position in the boot and shoe industry of Kettering was invited to come to Higham Ferrers to survey the position and discuss the prospects. Mr. Ashby had practical knowledge of the trade having served apprenticeship as a lad and studied the technical qualities involved in the fashioning and production of foot-wear while managing a factory in Kettering. The committee were impressed by his constructive criticism of the position and suggested his appointment as manager to clear the decks and put the society on the flowing trading tide—to the selling advantage of those who retailed footwear in the co-operative stores. He responded to their wishes; his management has amply justified the choice. The workers welcomed him in the spirit of Rudyard Kiplinq when he called for "the ever-lasting team work of every bloomin' soul." Three months later the committee reported to the shareholders that the new manager had made progress that gave hope "for a return to better times in the near future; expressions of satisfaction with the goods received by the distributive societies showed the confidence of the buyers and we commence 1935 with every confidence of a trade revival." In that energising season Mr. Solomon Upton, junior, who had been elected to the committee a few years before, was elected to the presidency and, in 1937, announced that the year's turnover had doubled that of 1934, While trade was improving, the cost of leather and other essentials were stepping upward. The institution of a new wages agreement, the amendment of working hours and the increased cost of materials proved a triple alliance for higher prices that continued till the World War toppled the Peace-time advance which had brought the factory at Higham Ferrers to the highest point in its history. The society had strengthened its position in the home market for men's wear as had the county as a whole. Mr. F. Lee, the investigator for Northamptonshire on behalf of the Nuffield College Social Reconstruction Committee, calculates that during the past two generations the output per man has been doubling as the result of improvements in boot and shoe machinery. Northamptonshire supplies four-fifths of the national demand for men's shoes; and about 7% of the national output of those for women—a section which the Higham Ferrers Boot and Shoe society has developed in artistic and fashionable style in recent years. In 1935 the county was responsible for 79% of the national output of men's boots and shoes as compared with 74% in 1924—and its reputation is striding well onward with Higham Ferrers directing "the clasping Ivy where to climb" in the windows of the Footwear departments that serve the main shopping avenues of the urban regions of the British Isles. Arthur Young, the 18th century poet observed that many people "their feet through faithless leather met the dirt." Since then they have learned the fidelity and longevity of that from Northamptonshire. Waterloo was not won on the playing fields of Eton, as was suggested by the scholars; our troops went forward well-shod in boots from Northamptonshire, as declared by the shoemakers in the county. And in the great conflicts of the present century British troops have marched to victory—in boots from the valley of the Nene. 1939-45 were anxious years of great endeavour. Government contracts for Army footwear on the outbreak of War reduced supplies for the Home Front. The men who remained in the "Ivy" factory worked overtime and, in the latter months of the conflict the shortage of female labour—when so many had gone from the factories to the fields with the Women's Land Army and other services—was a problem difficult to express in production. In 1940 the installation of electrical equipment throughout the works and new machinery in many sections quickened output and a trading record of £80,000 was made in 1942; but supplies to distributive societies had to be conditioned to national needs and much of that year's production was for Government contracts. Though their supplies were limited the co-operators increased the share capital to equip the factory to meet the urgent demands of H.M. Forces. Secretarial prescience guided the financial path to security; and the addition of a 1% bonus on the 3½% interest on share capital was welcomed by the societies which have invested in, as well as supported by trade with, the works at Higham Ferrers. In 1946, when Peace dawned and Army orders relaxed, the production of the highest grade of men's and youths' shoes and of a variety of fashionable footwear for the ladies went forward with appreciative welcome from retail buyers. Men's boots and shoes had proved their value for half a century. The more recent production of those for the ladies had met with equally good response from the managers of the distributive societies. Co-operators are naturally inclined to stand on their own feet—in their own shoes which, coming from Higham Ferrers, recall the tribute to the Ivy by Charles Dickens in the Pickwick Papers that: "A dainty plant is the Ivy green." And one of the young ladies in the office of the society tells me that the "Ivy" shoes are as dainty as the plant. Their display in the windows of distributive societies certainly confirms the compliment. The shortage of female labour in and about Higham Ferrers threatened delay in meeting the requirements of the retail societies so in the Christmas of 1946 the society linked with the kindred society at Wollaston in registering the Footwear Closers Ltd. to establish a branch factory in the co-operative and textile town of Blackburn where female labour is more available than in the Midlands. Parts of the uppers of shoes are sent to Blackburn to be joined up and stitched together on the high-speed power machines in the Closing room where the women and girls spend the day in friendly company. Good eyesight and skilful fingers determine the operations of the machines in reaching the standard of perfection required for the return of the uppers to the factory at Higham Ferrers to meet their soles and heels in the Lasting or Making Room. So the Footwear Closers play their part in the growth of the "Ivy" as was evidenced within a twelvemonth of the settlement at Blackburn. The Midlands saluted the Red Rose of the County Palatine. When the Board of Trade made a special export appeal in 1947 the society gave prompt response. Sales of over £100,000 for the year made a record in its history. Special displays of the "Ivy" shoes for women as well as those for men at International Exhibitions at Chicago and Copenhagen gave co-operative production a fitting place in the markets of the world. Northamptonshire was proud of the ancient borough in the valley of the Nene and the people of Higham Ferrers regarded the six-figure turnover as a tribute to the workmanship of their own folk. The proof of the pudding was in the eating for on its land adjoining the factory in the Chichele Street a spacious canteen was erected where willing workers eat and are merry in the mid-day leisure hour. Latterly the society has been fully engaged upon the manufacture of ladies' and gents' shoes for the home market and upon contracts for the Ministry of Supply. The cost of high-grade upper leathers has been rising but the consistent trade with loyal customers proves the confidence of co-operators in their own productive achievements and the committee look forward to a continuance of progress during 1950—after nearly sixty years of good endeavour on the co-operative highway. Fashionable Footwear The designers of the "Ivy" shoes are well in touch with the departmental managers of the shoe departments of the distributive societies whose experience they welcome in furthering the output. During recent seasons demand has veered with the drain of the Purchase Tax as well as the fitful weather, the scarcity of suitable leather for certain styles, and other disturbing factors. The present production of the factory covers the normal Plain Box and Willow shoe in Oxford and Gibson pattern. Good quantities of the semi and full brogue shoes in willow and grain are being manufactured—and meeting with the favour of the public. Sandals, casual shoes and platform wedge shoes in willow have been greatly favoured and while the narrow toe shoes of a few years ago have lost their appeal the good Fitting shoes of Full 5, 6 and 7 Fitting are now finding favour in the trade. All colours and types of ladies "Goodyear" Welted shoes are being made to meet the current demand. Here again weather plays its part in the rise and fall of production. Last year the autumn sales slowed owing to the weather remaining kindly and Bootees were the main request prior to Christmas. Good fitting semi-low heel ladies shoes still have a popular appeal as well as the Cuban heel on ladies' Court and similar shoes. Ladies' Casual and platform shoes are also in full production as well as Bootees for next autumn—ready for delivery early in September. For the footwear factory has to work to the seasonal time-table—like the Ivy. Co-operative Production and Co-operative Distribution are each the means to a common end. They seek the equitable relationship of the Factory and the shop. By eliminating the middleman and other capitalistic agencies the Co-operative Movement has become a national institution in which producer and consumer, or wearer, are linked in a circle of Goodwill. Departmental Details Truly the daily experience enjoyed in the modern boot and shoe factory is different to that endured by the operatives in the Queer Old Days. Not only are the interests of the workers in the "Ivy" factory guarded by the co-operative policy of securing the equitable relationship of producer and wearer but the national agreement between the trade unions and the employers' association has secured goodwill on both sides. In the "Ivy" factory at Higham Ferrers the workers are their own employers and, as trade unionists, they help their fellowmen to uphold the reputation of the ancient craft Nowadays folks fly like birds and swim like fishes. In the "Ivy" works they make shoes so they may walk like men—in step together. The co-operative factory has an educational outlook in training its young people to be masters of the machine and to develop their artistic sense with utility. Having secured a design that ensures ease and comfort to the wearer as well as an attractive appearance in service it is passed on to the pattern cutters and graders whose skilful accuracy ensures its advance to the foundational operations. The upper is cut out in the Clicking Room and then goes to the Closing room where women adroitly operate the machinery in joining and stitching the parts of the upper. Soles and heels are dealt with in the Bottom Stock Room and that known as the Preparing Room where they are made ready for joining to the uppers in the Making room. Thus assembled they pass on to the Finishing room where the bottoms are made. The uppers are polished on the way to the shoe room to be packed for despatch to those who want shoes of sound construction and good appearance. While the work is mainly done by machines their manipulation by the men and women, and boys and girls, demonstrates that heads as well as hands contribute to the gratifying result. Patience and skill co-operate for the resultant dividend of artistic accuracy that makes for comfort—from heel to toe. The secretary of the society, Mr. H. E. Newell, is a native of Higham Ferrers who has ministered to the welfare of the borough as well as the security of the "Ivy" works. Having qualified in the direction of office affairs he entered the service of the society in 27 and, in 1934, he was appointed secretary. Skilfully he has upheld its columns whilst harmonising with all sections in the factory and with the distributive societies whose secretaries welcomed him as a member of the Co-operative Secretaries' Association. Locally he has contributed to the social service of good neighbours. As sidesman of the parish church of St. Mary, with its 15th century tower and the fine craftsmanship of its west front, Mr. Newell has, for 25 years, upheld the Brotherhood of Man in Service above Self. And on the committees for Tuberculosis After-Care and the Higham Ferrers Motor Ambulance he has been a helpful influence to those in sickness or distress. For 20 years as secretary of the Earl Fitzwilliam Lodge of Oddfellows Friendly Society he has contributed to the goodwill of his fellow men. As a member of St. Mary's Football Club and the Higham Ferrers Cricket Club, he has, in winter and summer, played as well as he figures in the office of the "Ivy" works as a member of the C.S.A. As the years have rolled on Mr. Newell has migrated from the cricket pitch and the football ground and found scores of pleasures on the tennis court—always playing comfortably and well in shoes from the works whose statistical records he safeguards. Behind those statistical records is an asset of assured value in the goodwill and amity of the operatives in all sections of the factory at Higham Ferrers and its branch at Blackburn. They stride well together in the working hours and enjoy hearty association in their leisure ease. And everything must be timed to keep pace with the urgent orders of distributive managers anxious to gratify their loyal customers. In 1949 the boot and shoe factories in Gt. Britain made 146,000,000 pairs of boots and shoes. During the first three months of 1950 their output was at an annual rate of 150,000,000 pairs—equivalent to three pairs for every man, woman and youngster in the British Isles. Those figures should enable those in authority in co-operative footwear departments to cal¬culate the likely sales to the members of their societies—and the Higham Ferrers Co-operative Boot and Shoe Productive Society Ltd. will hurry along to supply their needs for THE PEDAL PRACTICE OF PRINCIPLE Better Business : Better Living The footwear departments of the co-operative societies are now responsible for the sale of 10% of the boot and shoe production of the country. This has been greatly due to the foresight and insight of the departmental managers in the selection of fashionable and serviceable goods to attract the custom of those seeking comfort on life's long road. Now that shop windows have become public picture galleries to attract strolling observers committees are wisely providing more ample facilities for shoe displays; and boot and shoe managers have been alert in recognising their responsibility in advancing the productive side of the movement for which they distribute. The Co-operative Boot Managers' Association founded in 1906—has become an authoritative influence in making co-operators "footwear-conscious" in selecting the shoes on which they walk. During the World War the proportion of the co-operative factor in the national boot and shoe trade steadily increased—despite restrictions and short supplies—as shown by Mr. J. A. Hough, M.A. in his recent volume on Co-operative Retailing. The Co-operative percentages were 8.64 in 193; 9.87 in 194; and 11.08 in 1943. Then the national output was mainly diverted to military need; but the co-operative sales have proved the constancy of those striving for the equitable relationship of producer and wearer. Sales are now being quickened by the production of fashionable shoes for the ladies as well as serviceable shoes for men. Married couples can walk in step together—on the shoes of the "Ivy" brand made by the Higham Ferrers Co-operative Boot and Shoe Productive Society in its modern factory where nearly a hundred happy workers—male and female—are associated in equitable relationship for the march of their friendly co-operators to the Commonwealth of Goodwill. Of 1,800, or thereabouts, of the boot and shoe works in Great Britain, 453 are in the East Midlands where Co-operative endeavours have proved their advance to "Better Business : Better Living" for those who work, or walk, on leather. Northamptonshire is bounded by nine other counties and its shoemakers have stimulated the heads as well as comforted the feet of working folks across the seas as well as those in the countryside. William Carey, the first missionary to India, came from the county and from his village at Ecton, near Higham Ferrers, Franklin went to America where his son Benjamin expressed the co-operative principle when he proclaimed that "God helps them that help themselves"—a thane that was in the minds of the men who found comradeship in working together in the workshop understanding in the valley of the Nene when the 19th century was nearing its close. Thomas Cooper, the Chartist who began his working life at the shoemakers's awl, was befriended by Charles Kingsley who, in his novel of "Alton Locke" envisaged the shoe-maker as a thoughtful member of Society guiding his fellows to greater understanding of their relation to each other. Thomas Cooper was the original of "Alton Locke" whose uncle was responsible for the youngster's start in life. "What could he make me but a tailor—or a shoemaker?" asked Alton, a pale weakly boy born in a crowded town. And Kingsley, who had helped the Christian Socialists to found the first co-operative boot and shoe society while they were drafting the Industrial and Provident Societies Act, 1852, answered the query in the novel that the workers of the 20th century should read to know the changing conditions in the last hundred years. "Have not clothes and shoes been the appointed work of such? The fact that the weakly frame is generally compensated," wrote Kingsley "by a proportionately increased activity of brain is too unimportant to enter into the calculations of the great king Laissez-faire. Well, my dear Society, it is you that suffer for the mistake, after all, more than we. If you do tether your cleverest artisans on tailors' shopboards and cobblers' benches and they—as sedentary folk will—fall a-thinking and come to strange conclusions thereby, they really ought to be much more thankful to you than you are to them. If Thomas Cooper had passed his first five-and-twenty years at the ploughtail instead of the shoemakers' awl, many words would have been left unsaid which, once spoken, working men are not likely to forget." Half a dozen worthy artisans from the shoemakers' awl spoke words of hope in their homely dwellings in Higham Ferrers, sixty years ago, which their sons and daughters in the "Ivy" works are not likely to forget Co-operators throughout the country can sustain their good endeavour by journeying to the end of their days on the "Ivy" shoes that uphold the associative principle of:— BETTER BUSINESS : BETTER LIVING ! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The factory closed in the 1960s - and was demolished in 2008. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||