|

|||

| By Jean Hunt (nee Ashton), transcribed by Donna Aitken, 2007 | |||

|

Memories of Working Life 1945-54 H. W. Chapman |

|||

|

|||

|

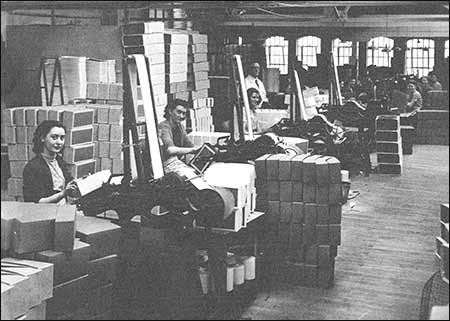

When the war ended and Dubilier Condenser Co. closed the Rushden branch of their factory down, I had to look for work elsewhere. Most of the local girls moved into the shoe industry, but as I hated the smell of leather I opted for Chapman's and cardboard box making.

Chapman’s factory was situated in

Because of wartime shortages still lingering, I found myself making brown paper bags! These were for the shoe factories to send their shoes off in and so were made in lots of different sizes. As this was not what the factory normally made, there were no machines for the job, so we made them all by hand. Sitting at trestle tables we had stacks of cut to size brown paper that we fanned into inch edges. We then pasted with large brushes, folded and stuck them together into bag shapes. It was only the pleasant group of girls I found myself among that decided me to stay for a while until I got myself sorted out with something different. Apart from shoe work, there did not seem to be anything but shop assistant jobs and the bus times from Souldrop did not fit in with the hours. The shoe factories were not yet geared up to usual peacetime work anyway, and with boots for the armed forces getting less, as men became demobbed and ammunition factories closed, special shoes were no longer needed. Men and women were returning to take up their old jobs in the shoe factories anyway. So, as cardboard became available again and Chapmans gradually returned to making boxes again, I stayed on.

The offices were also on the ground floor at the factory front. The head office of the firm was along the Embankment in Wellingborough, some seven miles away at a larger factory. There was also a smaller factory in Another job I had for a while in the factory was setting the measurements on a machine that cut the reams of paper into the widths required to fit the boxes for the 'banding' girls. I then had to watch that the paper did not tear nor run crooked on these smaller rolls when this machine was running. The measurements had to be precise. It was very tedious and the watching very boring. When the racks to one side were full of cut rolls, I’d stitch a few boxes or help out where needed elsewhere. Later I was put on a stitching machine of my own. The card had to be folded on the score lines and then stitched together in box shapes with wire staples. The machine was controlled by a foot pedal. The machines were driven by a belt through the floor onto a fly wheel from a shafting, running along the ceiling of the floor below. Gross after gross of them, all very repetitive work in a factory, a stack of card to one side, a dozen at a time, stacked on a bench the other side. Then this dozen laid on the floor and then each dozen on the top until a dozen high – one gross. 144 = gross 12 = dozen 12 x 12 = 144. The piles of boxes could then be pushed to the banding machines. After being covered they would have a label stuck to their end with a Company logo and shoe size printed on them. The labels were also printed in the factory. They were then sorted into orders, tied in dozens with string and sent down a shuttle to the loading bay below and so into vans that delivered them to the appropriate shoe factories. There was a small canteen where a mug of tea was made for us all on our ten minute break morning and afternoon. Those of us who could not get home for our meal at mid-day would take sandwiches and eat them sitting in a group or in nice weather out on the fire escape. Later when a café opened we’d go down to the bottom of We had a foreman named Walter Bone. Poor man, just him with all the girls on our factory floor! We must have run him ragged! There were a few more men, a couple in the yard and in the cardboard store. These also baled all the rubbish paper and card that went away for re-pulping. A few more men worked in the cutting room on the ground floor and in the delivery bay. Also the van drivers were all men. Mr. Gummer our manager was a believer in equality between office staff and factory workers. Usually you would find that office girls would not lower themselves to speak to the factory girls, but he would have none of that. As he rightly pointed out, no factory to produce, no office needed. Nor could the factory operate without the office. Mr. Gummer organised a social club to get us all mixing together because strangely there was a class distinction between certain jobs within the factory itself. Some of the printing and gold- stamping girls imagined that they were not factory workers! The social club would meet for different activities such as tennis in Spencer Park and swimming sessions at the town’s outdoor pool or ‘baths’ as we called it. I do not remember what else they did, as living out of town I could not join in on weekday evenings, but I did belong to the monthly Saturday rambling club. This I enjoyed immensely, as we rambled parts of the district that I did not know. One or other of us would suggest a particular walk and then lead it. The factory work was clean and not heavy and so I stayed on working there until I had married and was expecting my first child in 1954.

|

|||