|

||||||||||||||||||

|

From the "50th Anniversary Celebrations of the National Union of Boot and Shoe Operatives", written, printed and published by |

||||||||||||||||||

|

The 1905 Raunds Strike and March

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

From Raunds to London Incidents in The Great Strike of 1905 |

||||||||||||||||||

There is no doubt that this venture made trades unionism in the boot and shoe industry a militant force in this district, while the march to London by 115 strikers was a thing hitherto unknown. It aroused nation-wide interest and created an historic precedent in the matter of laying grievances before the highest authorities. Subsequent efforts on similar lines have not always been so successful, nor have they been carried out in so admirable and orderly a manner as Councillor James Gribble led his men to the House of Commons. However, even those who took upon themselves the serious task of calling the strike could have had no idea of the sensational development which was to follow eleven weeks later, a development which gave to Raunds a permanent place in trades union history. Some explanation is necessary of the causes which led up to the dispute, but these may be stated in comparatively brief terms. The actual strike commenced on Friday, March 3rd, but some months previously a conference took place between the Army boot contractors and the workmen and a statement of prices to be paid was agreed to. This statement was presented to the War Office and received official approval there, but it was subsequently ignored by some of the contractors, with the result that wage reductions were made in many cases. |

||||||||||||||||||

The secretary of the Rushden Branch of the Union, Mr. W. Bazeley, stated: "The work for the ankle boots is being given out at a 1d. a pair for closing the backs and the counters. It takes a good closer 10 hours to earn 1s., and she herself has to find awls and bristles. The statement price for this operation should be 2s. 6d. per dozen. "The ankle boot is being made and finished at 2s. 6d. and 2s. 7d. per pair, which is 8d. or 9d. under the proper statement price. It takes a good man to do eight pairs a week, and when he has done it at 2s. 7d. he earns £1 0s. 8d. Thus a skilled workman earns not an unskilled labourer's pay. "On the cavalry boots, and all the work which is being made on the sectional system, it is being done at 8d. and 9d. per pair less than the proper statement prices. "For mud boots, hand-finished, the statement price is 10d. per pair, but they are being given out at 5d. per pair, or a reduction of 50 per cent". These facts, briefly outlined by Mr. Bazeley, led to the situation at Raunds becoming acute. Mr. C. Freak, the general president of the Union, visited the district, and with Mr. Charles Bates and the secretary, interviewed one of the contractors. The interview was an amicable one, and Mr. Freak pointed out that the statement the Union was seeking to enforce had been agreed to by both manufacturers and workmen. Then mass meetings at Ringstead and Raunds Woodbine Club were addressed by Mr. Bazeley, Mr. Freak and Mr. Gribble, permanent organizer, and later strike manager. Resolutions demanding full statement prices were carried enthusiastically. It may be remarked here that Union members were assured of 15s. a week Union benefit and 5s. a week from the Federation funds, if they went on strike, which would be more than many were getting from regular employment. And so the momentous decision was taken. The Rushden Echo, in a leading article, commented on the position:

From twelve firms which refused to pay the statement prices, 300 or 400 came out, or gave a week's notice, and these factories were picketed. One firm agreed to pay and the men were ordered in accordingly, but a number of contractors at a meeting declared that they could not concede the demands of the workmen, it being impossible to pay the increased wages on the existing contracts. They also contended that the firm "giving in" to the Union had none of the contracts around which the dispute centred. Mr. Bailey army contractor, of Finedon, told the Union that he tendered for contracts on the statement prices and consequently was not successful in getting an order. He thought there was plenty of competition in the buying of leather, etc., without the contractors competing against each other in labour. How often has that sentiment been expressed in the nearly thirty succeeding years! A fortnight after the start of the Raunds dispute the number of strikers had risen to 500, while nearly 200 women were present at a meeting of closers, when Mr. Gribble declared that Raunds was different from other centres as the army boots were closed mainly by hand, and if the women stood firm the manufacturers would be defeated. At a meeting on the Square Mr. Gribble also advised the men not to pay rent to the manufacturers owning the houses in which they lived. In March 1905, the Rushden Echo published the account of an interview with Mr. Bazeley, who said, "I think the strike will finish this week, or certainly next week. The men have a strong case and we have reason to believe the War Office is favourable to our case. Again public opinion is with us, and the trade journals are in our favour. We think it would be suicidal on the part of the contractors to hold out. We must have full statement prices". Unfortunately that optimistic view did not materialize. During the following week a deplorable chapter in the history of the strike occurred. Hitherto the behaviour of all concerned had been exemplary, and although pickets had been organized and tin kettles and rotten eggs prepared for non-unionists, these "delinquents" were only hooted. On March 21st, however, there was mob violence, and wanton damage to property. On the Monday, some non-unionists who were at work at picketed factories were followed by a noisy crowd largely of children, beating tin kettles, and on the following evening as they left work an increasing crowd of 500 or 600 people followed them home, jostling, hissing, and hooting. The non-unionists were greeted with cries of "Blacklegs" and "Traitors." "Suddenly", wrote a reporter in a contemporary newspaper account, "one individual picked up a stone and hurled it at one of the windows of a non-unionist. The act was contagious. In a second the whole crowd became inflamed, the people losing all control over themselves. Hundreds of stones were hurled at the windows, every pane of which was speedily smashed. "Then the crowd looked for another house en which to wreak their vengeance, and immediately made an ugly rush to another non-unionist, where stones and other available missiles were thrown at the windows in a perfect deluge. "Only two members of the police force were on the scene, and they were utterly powerless to quell the disturbance, which had by this time developed into nothing short of a riot. House after house was attacked, scores of windows being smashed, and a vast amount of damage to property being done. It was not until nearly 10 p.m. that the police succeeded in dispersing the rioters, and by this time nearly all the non-unionists' houses had been attacked." Mr. Gribble, in the course of a speech later in the dispute, stated that photographs of certain houses that had been partially demolished as dangerous were published in one of the London papers as some of the wreckages of the strikers. So that while there is no smoke without fire, some account of the extent of the blaze must be read with discretion. However, the riots produced, not unnaturally, an unhappy impression, and the Union leaders were prompt in deprecating the mob violence. There is no doubt that it was largely the work of rowdy spirits, and very few of the actual strikers formed part of the crowds. Afterwards, however, special precautions were taken to prevent damage at picketed factories. On the day following the main disturbance (Wednesday), the arrival of about thirty extra police from the district was greeted with loud groans, hissing, and a continuous hammering of old tin cans. The day passed without incident, however, until 8.30 in the evening, when the hissing of the crowd outside the house of a factory manager culminated in a disorderly scene. There was a volley of stones, a sudden crash of glass, and very soon all the windows of the house had been smashed. The windows of other houses were also smashed, but with these exceptions the police were successful in preserving a certain amount of order. At the end of March the notice of the Government was brought to the dispute. In the House of Commons, Mr. Richard Bell, Labour Member for Derby, asked the Secretary of State for War if he were aware of the strike in consequence of the employers' violation of the fair wage clause governing contracts, and if he would inquire into the cause and insist upon the clause being observed in all contracts for boots for the use of His Majesty's Army. Mr. Arnold Foster replied that he did not understand the strike was in consequence of any violation of the wages clause of the War Department contracts, but that the strike was caused by the refusal of certain manu-facturers to adopt a schedule of prices which had been agreed to by some other manufacturers. If he had reason to believe the wages paid were not those current in the district (as required by the fair wages clause) he would cause an inquiry to be instituted. Mr. Channing asked whether the Secretary of State was aware that the statement of wages agreed upon and accepted by the War Office had been set aside by several contractors who had obtained contracts and were offering the work at prices lower than those agreed to. Mr. Arnold Foster replied that the statement did not represent the whole of the contractors of the district and it was afterwards partially repudiated. It was further never accepted by the Department as a scale of wages to be paid, but merely regarded as some evidence of a desire to arrive at a uniform scale. If and when the Department had reason to believe the wage clause was being infringed, steps would be taken to secure its observance. Commenting on this, the Leather Trades Review of April 19th stated:

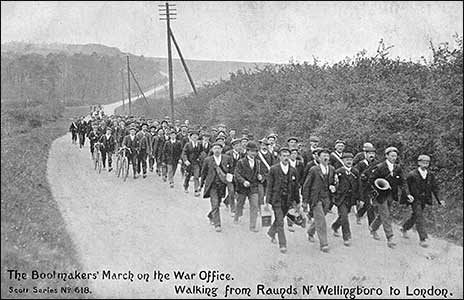

A word here on the financial aspect of the Raunds strike of 1905 might not be out of place. On a Saturday in March the Union distributed £140 in strike pay, and the Ways and Means Committee—formed to assist non-unionists during the dispute—paid out about £50. Nevertheless there was considerable distress among the non-unionist strikers and urgent appeals were issued for funds, in response to which Mr. Kingsmith, a manufacturer who had agreed to pay the statement prices, and whose operatives continued at work, gave £5 to the relief fund and promised 10s. a week for the duration of the strike. The National Council of the Union also donated £25 a week to the Ways and Means Committee. Subsequent weeks, following the noting, were comparatively quiet, and the only excitement was centred in charges of intimidation against a number of men, which were heard at Thrapston Police Court. The Union defrayed the costs of defending those who were summoned. On one Monday morning several manufacturers intimated that they would open their factories on the old terms, but only two girls went in for a short period at one factory and in all other cases the strikers remained firm. The strike drifted on and on until the ninth week of the struggle had passed by. Then some 300 drifted back to the factories at the old wages, but the stir which this might have caused at an earlier stage was over-shadowed by a proposal that the men should march to London to air their grievances to the War Office, and should they fail there, to proceed to Windsor on King Edward's return from Paris. Needless to say such a remarkable project created enormous interest, and led by Mr. Gribble, plans for the march by easy stages were put in hand with a minimum of delay. It was a momentous undertaking, and created intense public attention, at first in the county, and later all over the country. Did the organizers even then, one wonders, realize what a page of industrial history they were to write? There is no political significance in stating that with a Conservative government in power they were "bearding the lion in his den" in a way that had never been attempted before. Little wonder the county was stirred from end to end. Over 300 men readily volunteered for the march, but Mr. Gribble selected 115 representative strikers, picking out those who were likely to do the walk best. "We shall go to the War Office," Mr. Gribble said, "and present a petition, pleading to the authorities to interfere and insist on manufacturers recognizing the Fair Wages Clause in contracts. Failing satisfaction there we shall march to Westminster and present a petition to be heard at the Bar of the House of Commons. I know we shall be turned back, but the public will learn the justice of our demands. We shall not go to Windsor because that would be useless, but we shall take other steps to acquaint the King of the reality of our grievance." The following are the names, of the marchers, some of whom, in the course of succeeding years, have passed into the Great Beyond:- Chief: James Gribble. Officers: R. Baker (Paymaster), F. Roughton (Billetmaster), E. Batchelor, now assistant Branch Secretary (Commissariat-General). Cycle corps: J. Bass. G. Sawford and C. Mayes. Ambulance: W. Morris. "A" Company: Sergt. A. Coles, A. Coles, junior, and W. Allen, H. W. Allen, T. Chester, G. Underwood, W. Willmott, F. Lawrence, V. Willmott, M. Richards. S. Warner, R. Smith, C. Edwards, W. Robin¬son, E. Stubbs, E. Head, J. Hart and C. Allen. "B" Company: Sergt. A. Mayes, C. Higgs, G. Andrews, T. Moody, A. Bugby, C. Robins, F. Lawrence, Jack Allen, Fred Allen, Joe Allen, Will Allen, E. Betts, S. Jackson, R. Rooksby, T. Fensome, W. Cripps, F. Tear, J. Burton, E. Spicer and W. Mayes. "C" Company: Sergt. A. J. Green, J. Bates, G. K. Kirk, H. Webb, W. Webb, A. Webb, F. Smith, J. Brandon, E. Haxley, W. Atkins. G. Atkins, F. Gates, W. Allen, W. Nunley, F. Freeman, H. C. Clayton, H. Percival, A. C. Evans, F. Coggins, P. York and J. Ward. "D" Company: Sergt. R. Mayes, H. Phillips, W. Nash, W. Dilley, S. Ball, E. Spencer, G. Mayes, W. Sykes, W. Morris, H. Phillips, L, Pearson, E. Bird, J. Archer, S. Fensome, H. Major and R. Sawford. "E" Company: C. Copperwaite, F. Mutton. H. Reynolds, A. Green, J. Reynolds, T. Lock, F. Tilley, H. Ward, W. Whiteman, W. Barker, F. Bass, G. Haxley, F. Whitney, B. Mantel, C. Marsh, J. Cooper, H. Buntin, W. Archer, J. Scrivener, A. Ball, D. Nickerson and C. Lawrence. "F" Company (forming band): W. Robinson, B. Mayes, E. Collingham, L. Mayes, N. Fox, F. Fox, C. Dean, J. Warner, J. Denton, L. Hodson and W. Mayes. Sunday evening the men were drilled on a piece of land adjoining the Woodbine Club by Councillor Gribble, who, with seven years’ army experience behind him, was well qualified to put his contingent through the necessary movements. Each member of the deputation had a card containing the following,

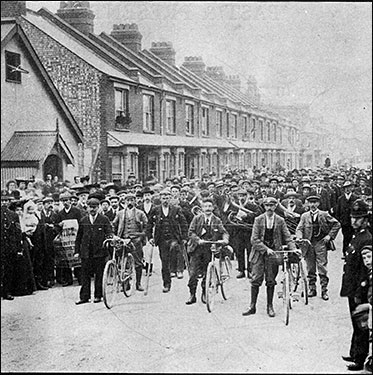

This course was taken to prevent any imposition by outsiders. The first day of the march commenced with a meeting in the Woodbine Club about 8.15a.m. addressed by Mr. Gribble, who, as usual, gave a stirring and compelling speech. His oratorical feats during the long duration of the strike excited admiration, and their stimulating influence must have done much to hold the men together for so long. He gave a further parting address on the Square shortly after ten o’clock, and then the bugle sounded, the five companies of men, amongst whom were several ambulance workers, answered to their names, fell into position, and headed by the band playing the lively march "Rebecca", were at once on their way to London. The great adventure had started. The men marched four abreast, with their rations on their backs, and the cycle corps, upon whom devolved the duty of billeting, purchase of food and the interviewing of the police authorities, formed an advance guard. It need hardly be said that they were cheered on their way by enormous crowds, "What ho!" called out one woman, " 'aint we 'avin a time, not such a time since Mary died." "General" Gribble led the way, a stout thick-set figure, who looked when marching as if he were wound up and not even the War Office would stop him"—according to an eye-witness's account. From Stanwick to Higham Ferrers and Rushden was a steady march. The strikers marched straight through the borough to the strains of "Edwinston", and the first halt was called at the Trade Union headquarters in Higham Road, Rushden. Then through Rushden, along a crowded street, where the marchers were accorded an enthusiastic reception; a sure indication of popular sentiment. Some had refreshment at the Coffee Tavern, but all assembled on the Green where Mr. Charles Bates, the president of the local Branch of the Union, presided over a meeting which commenced with the singing of "O ye moiling, toiling masses", sung to the tune of "Men of Harlech". Mr. Bazeley, in the course of an explanation of the wage reduction which had brought about the dispute, said some men were only receiving 7½d. and 6d. instead of the 9d. they were entitled to by the statement prices, and this meant to quick workmen a reduction of 13s. 9d. per week. At 1.40 p.m. the marchers left Rushden, followed by small crowds to the outskirts of the town. Behind the official body were four or five making the journey on their own account—one a lame man named John Pearson, from Ringstead, who with two crutches, insisted on going "right through", and refused many offers of lifts. At 6 p.m. Bedford was reached, and there halt was made for the night, though not before "General" Gribble had explained to a large crowd "what the fuss was all about". He explained how after the Boer War the price of Army boots fell from 4s., at which price a good workman could earn 32s. per week, to 3s. 3d., then to 2s. 6d., and later to 2s. 4d, by the manufacturers trying to undersell each other, and flouting the wages agreement in their efforts to do so. His address was received with rounds of applause. Tuesday's march was from Bedford to Luton, a start being made after the bugle had called the men, everyone of whom had found accommodation for the night. Headed by the band, Bedford was left to the strains of "The bright smile haunts me still", but whether there was a bright smile or not, there was certainly a bright sun and the walk was arduous. Kind offers of lifts, however, were refused, but the marchers were cheered by assistance given on the road. One gentleman who passed in a motor car contributed a sovereign to the funds. Just before the arrival at Luton the men were met by the Chief Constable of the town, who was impressed by their smart drilling, and the entry into Luton resembled a triumphal march. A welcome meat tea was provided by the deputy mayor, Councillor Oakley, and his brother. Mr. Oakley said that what he did for labour was only what he owed to labour, and he hoped they would be successful in their mission. Every marcher was then handed a cigar, and later the same evening an enthusiastic barber offered to shave the whole 115 men free of charge! Mr. Gribble addressed an open-air meeting, and then there was a welcome adjournment to bed. Wednesday saw an uneventful march through Harpenden to St Albans. At Harpenden, where a halt was made, some of the marchers look advantage of the rest to do some mending — with shoemaker's waxed thread of Raunds brand — and others went for a walk — just for exercise. St Albans was reached after a steady march. From Luton Mr. Gribble had sent a letter to the Secretary of State for War asking that the deputation be received, and a message was also sent to the Prime Minister, the Rt. Hon. A. J. Balfour, asking him to use his influence to induce Mr. Forster to receive them. A similar letter was also sent to Mr. Channing, who promised to support Mr. Gribble's application. A reply sent on behalf of the Minister on May 11th, however, was a refusal to meet the deputation, and stating that he did not consider any steps necessary other than those already announced. On the third day of the march the sum of £7 10s. 2d. was collected; evidence of popular support of the marchers, and it may here be mentioned that at the finish, when all expenses had been paid, there was a surplus of some £200, a remarkable achievement. At Watford, Messrs. Blyth and Pratt, blacking manufacturers, provided breakfast, and indeed the duties of the Billetmaster and Commissiariat-General were thus eased on both the outward and homeward journeys. Every day offers of lodgings were received from well-wishers of the men, and the only duties of the officers were to decide which offers of beds and meals to accept! At Cricklewood "General" Gribble suggested that if his men were to be feted as they had been every mile or two, their next feed should be "Beechams". Once in London, the arrangements were taken, in hand by the Social Democratic Federation, "General" James Gribble resigning his charge into their hands. From St. John's Wood to Hyde Park was a continual triumph, exceeding wildest expectations, and fully ten thousand people awaited the arrival there, and cheered the ensuing demonstration. A deputation of ten was appointed to proceed to the House of Commons, the remainder of the men continuing to Deptford, where they were accommodated. In Conference Room No. 1 at the House, the deputation met Mr. Channing, Mr. Shackleton. M.P., Mr. Will Crooks, M.P., Mr. Nannetti, M.P., Mr. Field, M.P., Mr. Henderson, M.P., Mr. Keir Hardie, M.P., and Mr. John Burns, M.P. After unsuccessful search had been made for Mr. Arnold Forster and Mr Bromley Davenport, the deputation was taken to the Strangers' Gallery, where it was found that a debate on the women's suffrage question was in progress. They listened for a time, while Mr. Herbert Robertson was speaking, when suddenly Mr. Gribble sprang up in the gallery and shouted, making himself heard all over the House: "Mr. Speaker, is this gentleman trying to talk out the time. For I've come here with 115 men from Northampton to try and see Mr. Arnold Forster". He got no further. Gribble had committed the heinous offence in the Mother of Parliaments, and he was forcibly ejected. A Gallery officer had his hand on his shoulder, and Mr. Gribble was led out. The Chamber had been startled into silence by the stranger's audacity, but when it was realized that the offender was the now famous "General" Gribble there was a wild stampede of members into the lobby to gaze upon the panting little man in the red tie. Several M.Ps. attempted to offer him advice, but suddenly Gribble broke away from the group and made a dash for the inner lobby which leads to the Bar of the House. So swift was his rush that he nearly got past two constables at the outer end of the corridor and he certainly gave them a severe struggle. Then, with twelve policemen round him, the "General" was led from the House. The lobby was full of ladies waiting to hear the result of the suffrage debate—indeed all around the House there were large crowds of women— and some of them screamed and called out, "What a shame," and "Treat him gently". Mr. Gribble's comment was: "It is bitterly disappointing". However, the deputation was able to take away with them the cheering news that a lawyer of high repute was to conduct an inquiry into the dispute, so that the men's endeavours had been far from wasted. Meanwhile the meeting in Hyde Park had been addressed by the Rev. D. Pughe, formerly of Irthlingborough, Mr. Ben Tillett, Dr. Clifford, and others. At Deptford Lady Warwick unexpectedly visited the men and was given a hearty ovation. On the Sunday afternoon there was an imposing demonstration in Trafalgar Square and among the speakers at three platforms were Mr. Gribble, Mrs. Despard, the veteran suffragette, and Keir Hardie, who afterwards accompanied the marchers to the tea at Whitfield's Tabernacle in Tottenham Court Road. Before the return march was commenced on Monday, May 14th. Mr. Gribble expressed satisfaction with the results of the march. "We are going back with sufficient funds to enable us to continue the strike" he said. The National Liberal Club subscribed to a send-off breakfast, and then the homeward trek was commenced, after a farewell demonstration in Hyde Park. The route lay through Watford, Chesham, Leighton Buzzard, Newport Pagnell, Northampton, and Wellingborough to Rushden. On Saturday Rushden gave the marchers a tremendous reception. They were met with music and processions, and opposite the branch quarters in Higham Road was literally a sea of heads. Tea and a wash were the first items on the programme and the immense concourse of people was addressed by Mrs. Rose Jarvis, of Northampton, Mr. Bates presiding. "The Red Flag" was sung by Comrade Frank Clark. Mr. Gribble briefly spoke, as he also did from the Market Cross at Higham Ferrers. Then on to Raunds, where a terrific reception awaited the men, and after a final speech, "General" Gribble was carried shoulder high to the Woodbine Club. The great adventure had ended; the most tremendous achievement in the long history of the stalwart workers of Northamptonshire. They had won through against tremendous odds, and the greatest credit is due to every one of them. The following was published in the Rushden Echo as the "March of the Strike Brigade":

During Mr. Gribble's absence on the London march, Mr. Bates was in charge of the situation at Raunds. Everything remained quiet except for a slight outbreak of window breaking, but Mr. Bates visited the town every day, driving over in a "buggy", or occasionally, with Mr. Freak, in a waggonette. He played no small part in successfully conducting the dispute and had the confidence of the men throughout. After the end of the dispute each one of the marchers received a handsome certificate in commemoration of the great event. The one presented to Mr. E. Batchelor now hangs, along with photographs of the marchers (a copy of each was also presented to each one of the men taking part), in the new Raunds offices of the Branch. Surmounted by a photograph of Mr. Gribble, it reads as follows:

Below this is a list of the marchers who took part. In the September report of the same year of the local Branch of the Union, it is stated that Councillor J. Gribble was presented with a marble clock, value £6 6s., subscribed by 300 Army workers, for his valuable services as dispute manager during the late strike. It will be convenient at this stage to deal briefly with the final settlement of the dispute. Mr. G. R. Askwith, now Lord Askwith, held a private inquiry at Leicester, and after a long deliberation the conference agreed to submit to the manufacturers and men concerned two statements of prices for their approval, one to apply for the remainder of the current contracts and the other for contracts in 1906. Under these statements the men would ultimately receive 2s. 11d. per pair instead of 2s. 5d. Explaining the position to the Raunds operatives the General President of the Union maintained they had thus secured a victory in principle, for it would establish a current rate of wages. Before the full adoption of the Statement in 1906 it was proposed that 6d. per pair less than the Statement be paid on present orders, except for the last 200 pairs, but a number of the men contending that they would thus return to work in a worse position, the Union representatives were instructed to press for the full Statement. Subsequent meetings with the contractors and with the Arbitrator produced no settlement, however, the employers' proposals being turned down by the Union. After a resumed meeting Mr. Askwith stated that a new offer by the contractors to the men on the current contracts showed an increase of a penny per pair upon what had been previously proposed, but by a ballot the strikers rejected the proposals by 304 votes to 33. It was not until after a thirteen weeks' struggle that a final settlement came. Slight concessions were made by both sides, and an important development was the setting up of an Arbitration Board, of which Mr. Bates and Mr. Bazeley became members. Mr. Askwith, addressing a final meeting of the men, said they had come out on strike to get an established rate of wages, and they had obtained it if the War Office would accept his report. They had therefore gained the principle for which they had fought and the settlement would be of the greatest importance to them all for future years. Mr. Askwith's painstaking services in bringing the sides together and effecting a settlement had been of vital importance, and he was deservedly accorded the heartiest thanks. The dispute cost the Union £2,064 7s. 7d., as well as £99 16s. 9d. subscribed by Branches, but it was agreed that the expenditure was worthwhile, the Government boot work having been placed on something like a fair and equitable basis. Mr. Channing, M.P., sent the following letter to the Secretary of State for War:

With these words we may appropriately close the history of the great Raunds strike. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||