The Rushden Echo 2nd July 1915, transcribed by Kay Collins

|

|

Serving King and Country

A Rushden Wireless Telegraphist In Far-away Bermuda

Lord Kitchener's Opinion

Islands Formed of White Coral

No Paupers and but few Invalids

|

|

|

|

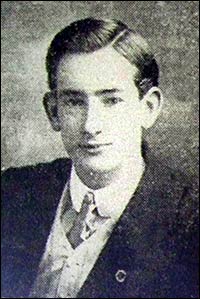

Mr. Arthur Vorley (son of Mr. and Mrs. B. Vorley, of Newton-road, Rushden) who is occupying an important position at the Government’s Naval Station at Bermuda, sends us a most interesting letter on life in that far-away portion of the empire.

Mr. Arthur Vorley went through a course of training at the London Training College for wireless telegraphy and cable work, and, although 12 months is the recognised term for students, he came through, with flying colours, in nine weeks. He writes:

As I read in the "Rushden Echo" of those who are serving their country in this war I thought perhaps a few words about another sphere of service in the war would be of interest. In our instrument room at the cable station of Bermuda we have posted up a letter received from Lord Kitchener to the effect that we are serving our country just as much as those who are in the trenches. This is indeed a charming spot to be able so to do. Here we are connected to Halifax (Nova Scotia), and Jamaica and Turks Island. The Bermudas is a naval station of the fleet, and has a fairly large dockyard. The dockyard is situated on Ireland Island and has the largest floating dock this side of the water, it being 381 feet in length and weighs 8,340 tons. It was built in England and towed out here by two steamers.

If one wished to see all the Bermudas at the rate of one island per day it would take just a year, for there are 365 of them. The entire area, however, is only 19 square miles. Some of the islands are so diminutive that you can scarcely see them. There are five large islands ... ... ... in a group in the shape of a shepherds crook, the middle or main island is the largest. Ireland Island is at the end of the crook and St. George's at the top of the handle. Then there is St. David's, that is reached from St. George's by boat, and Somerset that lies between Main Island and Ireland. A very wonderful causeway nearly two miles long connects the main island with St. George's, and there is a bridge between Somerset and Ireland Island and bridges between Somerset and Main Island.

St. George’s is a very quaint place, and most wonderfully well supplied with forts. They seem to be ranged along the entire water side, and, with the exception Gibraltar, Bermuda is the most strongly fortified of all British possessions.

Hamilton is the capital of Bermuda, and was made a city many years back. It possesses a fine cathedral and many imposing buildings. The main street, Front-street, runs parallel with the docks. The population of the entire islands in 1901 was about 6,000 white people and 11,000 coloured. The blacks are fairly industrious and well educated, speaking English grammatically, and with a marked English accent. There are no paupers in Bermuda, except a few pauper insane in the lunatic asylum, and a street beggar is unknown; and if one can judge from the statistics of the pretty little cottage hospital, where there are rarely half a dozen patients at a time, few of the citizens are invalids.

|

|

Arthur Vorley

|

|

The scenery is magnificent. Myriads of little white cottages, dotted all over the land, in bowers of purple and green and scarlet bloom, white roads twisting in and out from end to end of the island, a transparent sea girdling the land so crystal-clear that one looks down immeasurable depths upon coral rocks of all conceivable colours that reflect their soft shades on the waters above, and, over all, the sapphire sky. Blue was never so blue, nor green so green, nor white so white as in Bermuda. As one walks by the sea we notice the as colourings, shading from blue to forget-me-not blue, from vivid to delicate greens, from coral pinks to the rose tints; we can see the little fishes darting in and out of the yellow, red, and purple seaweeds, and look down upon the coral islands fathoms below. At every turn of the road new pictures come to view, and all about us glisten the pretty little cottages in their bowers of cedar, palm, and magnolia trees. Bananas grow in great profusion, and we also get oranges, lemons, grapes, strawberries, limes, sugar cane, etc. etc.

The whole island is formed of white coral, so, of course, it is all wonderfully clean. There is no dust or mud in the streets, for the rain is absorbed at once by the fibrous coral. The houses are built of soft coral limestone of which the island is formed. Digging into the coral for drinking wells, however, has not proved a success. Some wells have been found, but the water is very brackish, and the people prefer drinking rain water. Every house is requires to have a tank on the roof to collect the rain, and it is a law that the roof must be whitewashed annually.

The weather here is awfully hot and the humidity is very great. The perspiration streams off one, and the glare of the sun upon the snow white houses and roads is very tiring.

Here there are some wonderful caves. The stalactites glitter like gems. Antlers of amber stretched along the dome, long spikes of emerald hang from ruby rafters, diamond arrows shoot from bows of lapuslazuli, and cones of amethyst gleam from the dome. In the caves it is all very silent; only the sound of hushed voices and the ceaseless drip of the sparkling stalactites stir the stillness.

The strong sea air is anything but hospitable on first acquaintance: it bats you from every point. Very soon, however, this vigorous ozone becomes your champion and helps you to feel your feet again.

We practically live in and on the water, and have some great times. The water here is excellent for bathing and swimming, although there are a few sharks about, but they never come in near enough. On the south shore we get some fine fun with surf bathing. I live within two minutes’ walk of the water’s edge, five minutes’ spin on a cycle from the north shore, and a bout ten minutes from south shore, so one can get from one side of the island to the other in a very short time. Cycles are very popular here, and the roads are excellent in every respect. There are no trains here, and a law prohibits the use of motor cars of all descriptions, so we have no smoke from an engine and no dust from a car, but all is so peaceful and quiet that it really deserves its name of an Ocean Paradise. There are about 20 large hotels, and during the season, which extends from December to May, thousands from New York and other American places throng the islands. So my advice to all who wish for a good holiday, away from all the rush of busy towns, is ‘Come to Bermuda’.

June 1915 Arthur B. Vorley

|

|

The Rushden Echo, 29th October, 1915, transcribed by Gill Hollis

Rushden Telegraph Operator - In Far-Away Bermuda

Vivid Description of a Hurricane

A Four-Days’ Storm - A Wreck of a Steamer

Mr. Arthur Vorley, Government telegraph operator in Bermuda, writing to his parents (Mr. and Mrs. B. Vorley, of Rushden) says:-

“I am writing this letter (or rather commencing it) a week or ten days before the next mail boat leaves. I will tell you why. In my last letters I told you of the hurricane that was blowing here. Well, after doing damage and lasting for four days without ceasing for one moment, it gradually went down two days ago, and so the mail boat, after an awful time of it, was able to get out to sea. Well, yesterday it was fairly calm, but the sea in the harbour was running terribly high, so I thought I would go over to the south shore and watch the sea. Over there I got into a sort of pavilion, and the sight I never shall forget. Right on the rocks the huge green waves were pounding, making the spray all silvery, dash up for 30 or 40 feet (and that’s no exaggeration). Then 100 yards out to sea are what are known as the boilers, and on these rocks the creamy foam was surging, making a white line all around the coast. Then out yet another 300 yards were some more reefs which were getting the full force of the ocean, and the waves of huge dimensions hurled themselves against these reefs. Then beyond those was the broad Atlantic, with its mountainous waves, capped with foam bearing down to land with herculean strength. Thus, perhaps, you can imagine the sight I saw for two hours yesterday afternoon.

“As I was leaving I noticed the waves were getting considerably more angry, and I woke up this morning to find we are again in the midst of the hurricane. Outside the wind is blowing a gale (you cannot imagine what that is), and the rain, helped by the wind, is beating down in an alarming fashion. As I am not due at the office until 4 p.m., and as I find it impossible to get out in this wind, I sit down to commence (at least) my home letter.

“I have a lamp, as it is too dark to see without one, as all the windows are boarded, nailed, and tied up. The poor Halifax boat must be having

A Shocking Time

of it. It was due from the West Indies to call at Bermuda five days ago, and she isn’t in (and cannot get in) yet. We have had a wireless from her to say she is standing off Bermuda somewhere, and so they must be having the time of their lives. Where they sight the boats – St. George’s – they cannot see half a mile out over the water, and all telephonic and telegraphic communication with Hamilton and St. George’s Dockyard and the outer parishes is entirely cut off. Our wires to Dockyard are gone, and no boats are running, so the delay on Government messages is appalling.

“I am sure you will be sorry to hear that the magnificent organ at the Cathedral has been severely damaged. The roof leaked, and the organ is soaked. The downstairs of the Cathedral was on Sunday (and now again, I fear) under water – the surplices and everything are saturated. No electric light all over the islands, and nothing but wind and rain. Trees lying in the main roads, no shops open, and the streets in black darkness. We down at the office have had to get oil lamps, and they are awful things to work by.

“Occasionally a bang, and in goes a window. Then a roof of corrugated iron comes off with a crash, then a tree is lifted up by the roots, taken for yards, and flung down. The yachts, ferry-boats, etc., have broken from their moorings and drifted down the harbour, going to pieces on the multitude of islands in the Great Sound. Up here at Rosemont we can see the islands, and, as you look out through the wall of water we call rain, occasionally can be seen the water washing completely over the lesser isles. At night the light from Gibbs’ Hill Lighthouse cannot be seen for more than a mile – instead of 37 miles in good weather.

“But I am in a way enjoying the experience. It is something I haven’t experienced before, and I always did like a good wind. I find it is the worst storm they have had in Bermuda for a considerable time. The desolation was awful when I went out on Sunday during the lull – trees down and everywhere looked deserted.

“Since I wrote the first part of this letter we have had a most exciting time here. The storm moderated somewhat, but then came on again with increased violence. The barometer fell rapidly, and we were in for

A Hurricane.

It was very strange indeed, but at the very spot the day after I went on the south shore, and in the earlier part of my letter described the scene, the very next day, not about 14 hours after, a steamer was wrecked. The wind was awful, the sea broke right over her (and she was a large boat), and it ran on the rocks only 200 yards from shore; yet the rain was so torrential that you could only see the outline of the boat.

“O course, as soon as she sent out her distress signals crowds gathered, yet the sea was so terrible that no boat could be got out, and for a whole day the crew and passengers were huddled up in the bow, with a boiling sea breaking up to the masthead. Then during the night the boat broke right in two, with a fearful crash, heard above the thunder of the waves. Shortly after that they signalled to shore that the captain had been washed overboard and drowned; the others were safe, but starving. Then, as dawn broke through the rain, spray, and waves, the following signal was received from the ship: ‘Cannot last another day. If you cannot help we shall die.’

“Then the people on shore got frantic, and in the howling wind, driving rain, and tempestuous sea, time and again lines were sent out, boats sent out but capsized, and, after hours of battling a boat managed to get a rope to the wreck and made fast. Then slowly one by one was gently brought to land, to drop exhausted at the feet of their rescuers. It was a wonderful sight and a sight one rarely gets.

“I took my camera and got some snaps. I trust they are all right. One of the rescued men told me it was the finest piece of rescue work he had seen, and it truly was marvellous, for the sea was one seething mass. The body of the captain was picked up the other day. The coast is thick with wreckage. The boat, of course, is a total loss, and the men have hardly a penny of their own.

“Another boat just off Bermuda was wrecked at sea and abandoned, the crew being saved. Others limped in with their propellers broken, and so you can imagine what a time we have had.

“But it is all over now, and the weather has become “as hot as usual!” To-night (and I am writing this at the office at 3 a.m., being night duty) there is a thick fog – an occurrence that is very rare in Bermuda, and as you stand at the office door you cannot see the lights of Paget over the water (about three-quarters of a mile across).”

|

Rushden Echo, 27th December 1918, transcribed by Kay Collins

The Kaiser’s Vain Boast - "Conqueror of the World Now an Exile"

A Rushden Man Across the Atlantic

Mr Arthur Vorley, a cable operator at Bermuda, son of Mr and Mrs B Vorley, of Newton-road, Rushden, writing home on Nov. 13th, says:-

Our hearts are all filled with a deep joy and thankfulness to-day, for at last, after over four years of desperate struggling, and overwhelming losses of the flower of English sons, and untold misery, the despicable Hun has been forever overthrown. One can hardly believe that hostilities have ended, and that no more the roar of guns echoes through the fair land of France. What an inglorious end to such an autocratic empire—how she has crumbled—showing that she was in the last stages of decay. How vain the boast of him, once Emperor, now exile, that he would conquer the world. How contemptible of him to boost his people up with vain words, and as soon as his Empire crumbled to seek safety in abdication. His reward is commencing, and it is not inhuman to hope that the rest of his life will be nothing but extreme mental torture.

We, here in Bermuda, thousands of miles from the scene of the struggle, cannot commence to realise what the word “peace” can really mean. We here have never experienced the strain of war, the constant suspense, the daily anxiety. What must it be like to you at home, after so many years of tension. The daily news of casualties, taking for ever neighbours and friends, the trains of wounded, back from Flanders, crippled for life, the nightly expectation of air raids, the news at times bad, at times good; the ever increasing awful suspense of mothers who have boys at the front, wives who have their husbands there, and the hourly anticipation of that ominous telegram or letter from the War Office. To these, to you come the full blessed realisation and unabounding delight of the words “Hostilities ceased at 11a.m.” How your hearts must have filled with a joy unspeakably; how the 11th of November 1918 will stand out in history as the day you live again.

Our hearts—the hearts of all true Britishers and Englishmen—swell with pride to know than what England has set out to do she has achieved, the cutting away of the cancer Prussianism from out the world. In 1914 men looked stern yet resolute, they had a Herculean task before them, a task before which the bravest might flinch; yet despite reverses, despite losses and retreats, the nation carried on, and for four long weary years they struggled on in silence. No vain words or vaunted speeches, as they that fell from the Kaiser, saying “Gott” was his Ally and victory was certain. No, the Allies knew right must win the day, and they were on the side of right.

It has been a long hard fight against and enemy prepared for forty years and armed with every hideous man-killing device, but what an end! The crumbling down of empires as a pack of cards! Who can but feel proud of England, the champion, the bulwark and mainstay of the war? Our pride and joy is absolutely justifiable.

Everyone has lost in this war: many, alas, have lost their loved ones: many will carry the marks of conflict to their grave, while others have had their share in the loss of personal comforts and general shortage.

The news of the signing of the Armistice at 5a.m. on the 11th reached Bermuda at 5.30a.m. and we were immediately awakened by the booming guns and the whistles of scores of boats, accompanied by the deep base siren of the Halifax boat which was in port. We got up—for who could sleep?—and it thrilled the heart to hear the cheering and see the flags fluttering up in the breeze from a hundred flag staffs. Proudly we listened to the strains of “Britons never shall be slaves.” All Hamilton was soon a mass of flags and bunting and everybody was in the city and all the stores closed. And if Hamilton was so joyful, what must England be?

Later in the day many rejoicings were held and everywhere was happy. Lighting restrictions were lifted, and bonfires lit up the skies. The next morning we received the terms of the Armistice, and for Germany to accept such terms she must be in a very bad state.

Thus ends the most terrible of wars, and may we be able to say it was the last of wars. It was a complete victory; given a few more hours doubtless the enemy would have been driven from France, and all there was for them to do was surrender. So the seemingly impossible has been achieved, and the greatest military power has been brought to confusion; no wonder we rejoice.

I can imagine your celebrations; I can picture Rushden one mass of flags and jubilation, and I long to be with you to share that joy.

Although November is half over, we still enjoy our swim, and the water has a sharpness that is very pleasant.

|

|