|

|

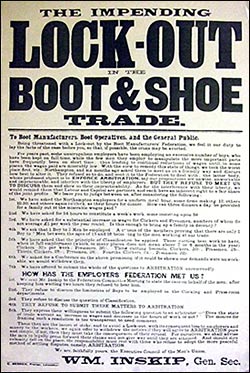

The poster for the impending Lock-out

|

To Boot Manufacturers, Boot Operatives, and the General Public.

Being threatened with a Lock-out by the Boot Manufacturers' Federation, we feel it our duty to lay the facts of the case before you, as that, if possible, the crisis may be averted.

For years past, sorme unscrupulous employers have been employing an excessive number of boys, who have been kept on full-time, while the few men they employ to manipulate the more important parts have frequently been on short time; thus leading to continual reductions of wages, until, in some cases, the wages paid are miserably low. With the view to remedy this state of things, we took the worst place first, viz: Northampton, and six months ago asked them to meet us in a friendly way and discuss how best to alter it. They refused so to do, and sent it to the Federation to deal with: the latter body, whose professed object is to ENFORCE ARBITRATION, say our propositions are unwise, unworkable and impracticable, and interfere with the liberty of employers. BUT THEY REFUSE TO MEET US TO DISCUSS them and show us their impracticability. As for the interference with their liberty, we would remind them that labour and Capital are partners, and each have an inherent right to a fair share of the joint profits We leave you to judge between us, after considering the following:

1st. We have asked the Northampton employers for a uniform meal hour, some firms making 12. others 12.30, and others again 1 o'clock, as their hours for dinner. How can three dinners a day be provided for a family out on the miserable wages paid?

2nd. We have asked for 54 hours to constitute a week's work. Some insist upon 56.

3rd. We have asked for a substantial increase in wages for Clickers and Pressmen, numbers of whom do not average £1 per week the year round. Is this enough to bring up a family in decency?

4th. We ask that 1 Boy to 3 Men be employed. A census of the members proving that there are only 1 Boy to 7 Men between the ages of 13 and 18 belonging to the men working at our trade.

5th. We have asked that the principle of Classification be applied. Those cutting best work to have, when in full employment (which, in many places does not mean above 7 or 8 months in the year) CIickers 32/- per week. Pressmen 30/-. Those cutting Seconds, Clickers 30/-. Pressmen 29/-. Thirds. Clickers 23/-. Pressmen 26/-. Fourths, Clickers 24/- . Pressmen 22/-.

6th. We asked for a Conference on the above, promising, if it could be shown our demands were unworkable, we would withdraw them.

7th. We have offered to submit the whole of the questions to ARBITRATION unreservedly.

HOW HAS THE EMPLOYERS FEDERATION MET US?

1st. We sent Mr Inskip to the Federation Committee Meeting to state the case on behalf of the men: after keeping him waiting two hours they refused to hear him.

2nd. They refuse to discuss the limitation of Boys to be employed in the Clicking and Pressroom.

3rd. They refuse to discuss the question of Classification.

4th. THEY REFUSE TO SUBMIT THESE MATTERS TO ARBITRATION.

5th. They express their willingness to submit the following questions to an arbitrator:- "Does the state of trade warrant an increase in wages and decrease in the hours of work or not?" The motive for framing such a resolution is too transparent, to need comment.

These then are the issues at stake, and to avoid a Lock-out, with its consequent loss to employers and misery to the workers, we again offer to withdraw the notices if they will agree to ARBITRATION pure and simple, if not, then they must take the consequences of their refusal. For ourselves, we shall advise the men to legally press forward their claims and not give way until they are attained. And should dire calamity fall on the place, the responsibility must rest with those who refuse to adopt the more peaceful method of settling disputes, namely, ARBITRATION.

We are, faithfully yours, the Executive Council of the Men's Union,

WM. INSKIP, Gen. Sec.

|