|

Mrs. Sturgen.

Well, the first thing I can remember about the war was the morning that it was announced on the radio. We went, I would be about nine years old and we went up to my Aunt Net’s house who lived a couple of doors away from us. I knew it was something serious and we all sat together in Aunt Net’s sitting room and Neville Chamberlain made his speech and he said. ‘And now I have to tell you we are at war with Germany.’ Aunt Net cried and then they played the National Anthem and we all stood to attention, I can remember that as well as anything.

Now the next thing I can remember was we had to be fitted with gas masks and a man from, I presume the ARP or somebody like that, came round to our houses and they fitted us with these gas masks and made sure they fitted you right around the side of the face so that there weren’t any openings. You put these gas masks on and then everything went all steamed up because of the moisture in the air so you couldn’t see out of them. Then my sister had the bright idea that if the bombs dropped our teeth would clench and our eardrums would burst. So she bought some garden sticks and we were supposed to clench these garden sticks between our teeth. Of course being not very old I thought, well, how was I going to have garden sticks between my teeth with the gas mask on. I couldn’t work out how it was going to happen at all. We all took our gas masks to school in cardboard gas mask cases but they didn’t last very long. You could buy Rexene gas mask cases or you could perhaps knit a gas mask case and they became quite a fashion item. You might get a gas mask case for Christmas or something like that.

The same with identity discs. First of all we had a little, would it be plastic, a little plastic disc around our neck on a ribbon or something like that with your name and address on. But then they got to be metal ones where you had your name and address engraved on them and they were another fashion item. All children wore an identity disc as far as I know because I suppose it was to identify us if we died. But we didn’t know that at the time, we just thought they were another piece of jewellery.

Then the blackout that was you know, very serious, you didn’t have to shine a chink of light, not a chink through the curtains or anything. They painted the windows of the buses with a blue paint, so the lights didn’t shine out as they were travelling along in the dark. And even the headlights, the moon, they’d be blacked out with this blackout paint. And you bumped into people but the one thing about the blackout was the moonlight nights. The moonlight nights were like nothing you’d ever see nowadays because you just see for miles. We lived near the fields and you see right across the fields, all the scenery bathed in moonlight. I remember they said that the night Coventry was bombed it was one of the loveliest moonlight nights in living memory.

So, then we’ll talk about sweets because sweets went on the ration and that was a real hardship. We had three quarters of a pound of sweets per person each month. Well, it wasn’t very much for anybody, a sweet lover like me and of course all food was rationed as well. I didn’t take so much notice of that because that was the mother’s role, to eke out the rations. Soap was rationed but things like saucepans and pudding pans weren’t rationed but you couldn’t get them. So, if Woolworths had a consignment of saucepans in people would go and queue up and buy a saucepan. Didn’t matter what colour or size as long as you’d got a saucepan, that was what you thought you’d got to treasure. I can remember going down to Woolworths for my mother because she was at the cafe and got a saucepan for her. My Aunty Lily worked at the cafe as well and she said. ‘Would you go and get me one as well,’ and I went back to get one and they wouldn’t let me. They said. ‘No, you’ve been once you can’t have another one,’ and I said. ‘Well it’s for my aunty,’ but no, they wouldn’t let me have it.

Clothes were rationed of course. For people like me, I would have to wear hand me downs very, very often. I might have a cousin’s coat or dress, not shoes but anything like that because you had to save the coupons. People that were grown up couldn’t have hand me downs, but people were known to unpick jumpers and knit another garment up with them. I know a lady who made her baby brother a romper suit out of an old wedding dress. You just made do and mend with clothes and an aunt of mine and her friend, they swopped coats because they both got fed up with their own.

|

|

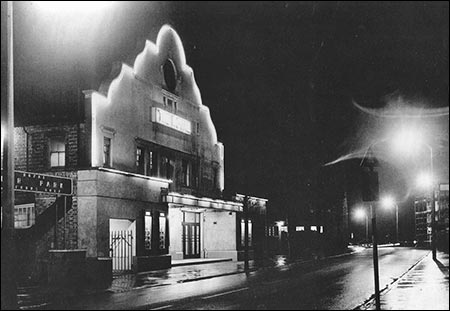

The Theatre Cinema Floodlit

|

There wasn’t much social life after work because there wasn’t any television or anything like that. Everybody went to the pictures, you could go six times a week. There were three picture houses in Rushden, The Palace, The Ritz and the Theatre. So you could go Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday and then Thursday, Friday and Saturday. Not that I ever did that but I used to love to go to the pictures. I can remember, I wasn’t very old, and I was allowed to go to see a picture with my friend Pat. There used to be two pictures, a little picture and a big picture: so we saw the little picture ‘Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy’ about two rag dolls. Then there was the big picture and it was continuous you see so ‘Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy’ came on again. Pat and I decided we’d stop and see that as well until my mother came along and dragged us out. It was past our time that we were supposed to be out, got into trouble about that. Another thing was visiting relatives, everybody visited everybody else in the evening. They’d perhaps have a cup of tea and a biscuit, if they’d got one.

The next thing I remember was when Alfred Street School was bombed. It was an October morning and the only thing I can remember was the ceiling falling in on top of us. As we ran out of the door the glass was still falling out of the windows onto us. Then we went into the air raid shelter and one teacher was walking up and down the air raid shelter. She’d got a torch and she was singing ‘Roll out the Barrel’ and some children were screaming and some were crying. I was just so shocked, I didn’t do anything, and I never said anything. I just sat there and my aunty came in to look for her son, and I daren’t put my hand out to touch her. I just sat there frozen and it wasn’t until my other aunt came in and fetched me that I moved. But we got over it, we didn’t have any counselling or anything, it just happened, and then we had to get on with our lives.

Then we moved from Alfred Street School up to a church in Highfield Road, where we had lessons. It was a bit of a long walk for me because I had to go from Higham Road, right up to Purvis Road. Then I went to Wellingborough School and I didn’t pass the exam so my mother paid for me. It was I think about £3 10s a term, then she had to pay the bus fares, 7d a day return, and then school dinners were 6d a day. So I suppose it was pretty expensive but I was lucky to go really. I didn’t shine at school, I wasn’t particularly clever, but I quite liked it, it was alright.

We had to go potato picking though, while I was at school, and we went to Wilby on the bus I believe and all congregated there. Oh, and I hated this potato picking lark, I really, really, hated it. It was cold and wet while I was there and this tractor used to come round and hurl potatoes at you and then you had to put them in a bucket. We all sat under a hedge having our sandwiches, or whatever we’d taken, and the farmer’s wife came along and brought us some cocoa. The rain and the mud then when we went home, taken back to Wellingborough in what I can only describe as a muck cart, and it really was beneath my dignity. I didn’t like it at all, but there you are, we got paid for it, that was one thing.

Then you had to queue for everything, I mentioned about the queueing for the saucepans but it wouldn’t matter what it was. If it was number eight batteries, they were little batteries for fitting into a torch and they were like gold dust. If anybody had got any batteries, whether you wanted any or not, you’d go and queue for them. There were just queues, if somebody had some oranges in they’d say. ‘Ooh, Seabrooks have got some oranges in go and queue for them.’ You know, everything was queued for. At the cafe they were allocated so many biscuits per quarter and my mother would only serve biscuits to people with children. Grownups never had biscuits, so if you’d got children you could have a few biscuits on the plate. As I say you’d queue to go to the pictures, you queued for a bus, you queued for oranges, you just queued for everything, for anything you could get.

Then I remember holidays at home, because you couldn’t go to the coast on holiday. They used to organise holidays at home. A week’s recreation at Hall Park and there’d perhaps be a parade and the Americans would all march round. The tanks churned the Hall Park lawns up and everything else where they were on display.There were all different side stalls and homemade stalls.They were the holidays at home and then we just sort of got through the war. Roberts Street was bombed and Alfred Street School was bombed and the incendiaries all dropped over Rushden.

I was lucky I don’t remember any real hardships. I was never hungry and I don’t think we were ever short of anything, we never knew we were deprived, if we were. The only thing I do remember is being cold. I remember being very, very, cold because you only had so much coal allocated to you. Ours was a big house, it didn’t matter what size your house was you still only got so many hundredweight of coal. I used to have a liberty bodice and a vest, knickers and stockings and goodness only knows what, I remember that quite well.

The end of the war just sort of came and I was still at school. We all laughed and joked, screamed, cuddled one another and that was it really. Then my brothers were demobbed, home from the war and gradually we just picked up the threads. Of course, sadly my dad died in 1942, so he didn’t see the war.

|

|

Tarry's Factory

|

I worked in Tarry’s Shoe Factory because in my day you didn’t go to University unless you were exceptionally clever, gifted or you wanted to be a teacher or a doctor or something very special. Mostly girls of my education either went into a shop or a factory office. I went into a factory office, I worked at Tarry’s for a little while, and then I applied for a job at the Telephone Exchange and I stayed there until it went automatic. Then I went to Eatons’ Shoe Factory office and got married and left to have Rachel, and that was it for a long, long, time.

Mr. Sturgen.

It was during the blackout and my father and I was on the way home, about seven o’clock in the evening along Park Road. It was as black as anything, you couldn’t see a thing. You knew where you were, but you didn’t, if you know what I mean. All of a sudden, bang, bumped into this fellow, sorted ourselves out and got on our way. But when I got in home, took my coat off and opened my coat and, he was a pipe smoking man, and his pipe was wedged down the front of my coat. It had made him gasp and I suppose he shot it out of his mouth. Anyway, that was that, I never did see him to give him his pipe back.

Anyway, that was at a time when I worked with my father. He had a small components factory and fittings for the shoe trade, clicking. Prior to that, when I was at school, I used to do his errands, taking the work he’d done back to the factories he was working for. They had what they called leather bits, the scrap leather that was left, he’d bag it up and it would be ditched. But I had a regular round of ladies who did washing. They had little coppers in the back outbuildings, up the yard, and they used to burn the leather bits on there because it was cheap and nobody bothered about the smoke then. I had a regular round, same women all the time, different streets round my area. I was never short of money, 3d a barrow I used to get for it, I was never short of money, always got money in my pocket. I had a little truck that I took them on until I left school and went to work for my father, I was there for nearly three years.

The war was on now and the time came when they were looking for boys to go to down the mines, Bevan Boys. I didn’t want that so I went and volunteered for the Navy and I went in when I was just over seventeen. I went to Skegness, Butlins to the start. That was a Naval place, HMS Royal Arthur, kit you up and everything. You’d do a fortnight there, getting your kit and your inoculations and whatnot, go to the dentist and they’d look you over. Then you moved on to another place which was Malvern, in the Malvern Hills to do a bit of a little bit of training which weren’t much at all because I wasn’t a seaman or anything. I was in the engine room department when I started doing my engineering training, I went to Plymouth and I was on an old battleship there. I was there for I think about three months, doing the training and moved on from there. Then I went into barracks and waited for a ship.

My first ship was The Illustrious and that was up in the dry dock in Rosyth, Scotland. Went up there and pinked it up, of course we weren’t at sea because we was in the dry dock. I was on there quite a while and then the King came up to inspect the, of course there was a bit of a hoo-ha up there then. When he left he said. ‘Splice the mainbrace.’ But I was what they called underage so I didn’t I didn’t get any. From there I went back down into Plymouth barracks. I was there for a week or two and then I had another draft out to the Mediterranean. From there I went more or less, not all over, but pretty well round the Mediterranean. I went to Alexandria in Eqypt, all round the Greek Islands. Up the Adriatic, all over Malta, I was in Malta quite a while which was quite an experience, you know. Done about two and a half years out there, came back and then they started demobbing.

I went into barracks and they give me what they called ship’s company down in Devonport harbour and was there more or less waiting for demob. They took you in numbers, waited for my number until it came up. I was, I should think, about six months and then my demob came up. Came home, oh, yes, when you was demobbed in those days they kitted you out. A suit, shoes, right through: a mac, or overcoat, shirt, tie, the lot. It was alright, a bit, what do they call it, utility, the suit was. A little bit of what they called demob money at how long you’d been in, they paid you so much extra. Got that, which wasn’t a lot really, went down to Portsmouth to get this demob done and the best part about it, were the shoes. They were really good shoes, they were made at Desborough, Cheanies at Desborough, I remember that on the bottom of the sole. Came home and went back to clicking again for quite a, well a good ten years. Oh, yes, I met Madeline and we got married. About ten years I was like that and then the shoe trade started getting a bit tricky and there wasn’t a lot about really. So, I changed tack and I got a job in Bedford with an American firm, Texas Instruments. Went there, a very good job that was, earned good money. I was there for about twelve, thirteen years and then I had a bit of illness.

|