|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adapted from the book 'AROUND MY NATIONAL SERVICE' by Peter Harris | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

AROUND MY NATIONAL SERVICE

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Memoir of a Boy Survivor via an Apprenticeship and the Korean War to

Civilian Life and a Lectureship. A SCRAPBOOK PETER HARRIS |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

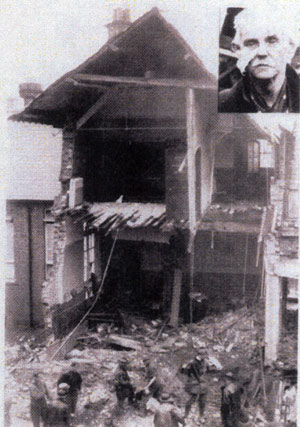

EXTRACT FROM A TRIBUTE (The Bombing of Alfred Street School).

Dennis Felce was my pal and we were usually to be found playing soldiers. If we saw a real soldier, salutes were often exchanged. His dad had a magic lantern and a small steam stationary engine, which we were intrigued to play with from time to time. I was nearly nine and in Miss O’Connor’s class. Dennis was younger and in Miss Wright's class. He was well loved but on that Thursday morning he had been up to something, which had upset his mother so, he had gone to school without his usual departure, a kiss from his mother. At around mid morning, a violent crump, as sudden as a clap of thunder punched the building from the left! Brown dust and smoke swirled across the classroom to the right and the floor was suddenly an uneven hump. Desks were displaced and some of us were on the floor. The force lifted me, and I remember being inclined forward and to the right. The blast toppled over the cupboard near the door to the hall and escape to the right was urgent. Another crump, a second or so later just outside in that direction checked this impulse as the big windows shattered to cascade glass all over the floor and adjacent desks. The playground and one of the shelters had been blasted open to form a crater and a high bank of rubble. It was between us and another shelter. We climbed and scrambled, reached the shelter and sat down on the narrow benches inside, in order to come to terms with what had happened. It then began to register with us that we had been bombed by a German plane. (Many said later, that had there had been a warning siren, children would have been in the destroyed shelter and there would have been more people killed).

Margaret and David were taken home and people continued to discuss the effect of the bombing across the town. Their dad had gone back to the front of the school and alongside others they helped the local service workers to look for survivors. My mum and others helped some of Cave’s factory workers to fortify these cleaning up teams with tea and sandwiches. They learned that four workers had been killed and that one of them had to be eased down from a roof truss. There were also many casualties. In the evening I remember being told that Dennis and six other children had been killed and that they lay together in

GRAMP AND GRANDMA HARRIS. Gramp was a farm labourer who was bold rather than mild. He played the euphonium in Irthlingborough Town Band and in a wholesome way he reminded me of H.E.Bates’ ‘My Uncle Silas’. He became a shoe worker in the co-operative shoe factory near to where they lived in Rushden. He had a cosy workshop accessed by a door through the kitchen. He retired early and made and repaired boots and shoes. His other hobby was vegetable growing on his twenty-pole allotment about a mile and a half away. Leather bits from the factories were an important source of fuel for the kitchen coppers and the workshop fireplaces. He used to use the horse and cart to collect the bits and take them to the

I can’t remember Gramp or Grandma Harris ever going on holiday or even going out for a day. They used to walk to

Evacuees came from

At school we would have drills in case of further bombing. We would get underneath the desk and bite crossways on a pencil. On several occasions when we were in the playground, B17’s (Flying Fortresses) would come over on fewer than four engines and with bits of tail or wing tips missing. On an afternoon bike ride with a pal we were in a sunny tree lined lane at Wymington when there was a roar overhead and a flying fortress at tree top height flew over, obviously making for the base at Chelveston. We were intrigued to see several of the crew quite clearly, especially the port side gunner. Suddenly it had disappeared. In half a minute or so there was a tremendous crump. We knew it had crashed. Cycling over in that direction, eventually we saw it enveloped in smoke and flames, attended by fire engines and ambulances. We could only make an obvious assumption about the crew. However, I have discovered quite recently that several local farmers, who were nearby, were able to pull clear and save some of the crew. MY APPRENTICESHIP. From January 1945 to October 1951, Arthur Sanders Limited employed me alongside about 90 others, based at the Newton Road ‘Top Yard’ which was a site for storing building materials and a facility for constructing packing cases for shipments of boots and shoes for local factories.Making packing cases did not require much initiative and I soon began to feel frustrated to start my apprenticeship at the ‘bottom shop’, the headquarters in

The workshop was a large tin shed, which was very cold during winter. Stoking the boiler with coke and off cuts of timber would only make a psychological difference to the temperature. Naturally, not all of Les Clark’s coffins were for adults. There were little babies who had not survived birth and who had coffins little bigger than shoeboxes. A large clean carpenter’s tool bag was reserved for carrying these and I would respectfully hang one over the handlebars of my bike and carry it to the local cemetery to hand it over to the superintendent, Mr Moisy. Roy Robinson joined the team from being a student at

At last we both transferred to the ‘bottom shop’ in

I spent a great deal of time working with Albert Dickens, the best role model I could have had. We worked in Grenson’s shoe factory for about two years, rebuilding the offices with wooden partitions. A large amount of second-hand timber was used, mainly red deal and we thought nothing of ripping a nine-foot long length of 4”x3” timber down the middle with Albert’s ripsaw, 3 teeth to the inch. Later I made my own from an old saw of Gramp Harris’s, 6 teeth to the inch. We once fixed slides and made a template so that plasterers could copy an intricate ceiling cornice. Albert had a long circular section claw bar but he decided to halve a six-foot length of hexagonal section steel, he had to make two more, one each! We made a hardboard pattern, which I took with the steel to the blacksmith. The result was first class. Albert was well read and I was happy to follow his day-to-day philosophy. His practice was to lay the dust with a spray, and then sweep up. We would leave a sink cleaner than we found it. Shoes were cleaned every morning and we always removed protruding nails from discarded timber. In tandem with my apprenticeship I attended night school at

Occasionally I would have to push ‘the builders truck’ fully loaded up through the streets and past the High/Grammar School students waiting for buses to Wellingborough, I felt that that was where I ought to be. Architecture appealed to me but I couldn’t see how I could take a step into that profession. Technical Education seemed to be my only answer so I followed in the footsteps of a slightly older chap who had been an apprentice and a part-time student. Employers followed the tradition that even at the end of a five or six year apprenticeship you still needed an extra year as an improver. As I was reluctantly conscripted into the P.B. Infantry, I avoided this ploy, which was about five pounds a week. NATIONAL SERVICE. World War 2 ended in 1945 and brought to a close one of the worst periods for mankind in history. National Service began in 1939 and continued until 1960. My involvement was from 1951, when I was called up until 1953. Its focus was the third and final year of the Korean War (1952 to 1953). It was not until we became involved in

JOINING UP AND TRAINING IN

When I was thirteen I had joined Rushden Newton Road Evening Institute at Dads suggestion for classes in mathematics and woodwork. During my apprenticeship I attended

I was extremely ambitious to become a mathematics lecturer in a college. During my business studies I became increasingly interested in mathematics. I remember when I was eighteen, in one lecture at

I was prejudiced when I joined the army but made the most of it by studying whenever I could, appreciating interesting places abroad and most of all, becoming enriched by the many varied friendships that were formed. However, later on I did become aware that there are many excellent careers to be had in the services. After a two year deferment I had to report to Northampton Drill Hall for a medical. There was no chance of getting into the Navy, and the Air Force only took you if you were prepared to sign on for three years. Obviously, I opted for Army Units, which related to my interests, including the Medical Corps. The selection process was farcical, however, as I ended up in the Infantry. The home of the Northampton Regiment (The Steelbacks) was the Quebec Barracks. Northampton became my destination, and I found myself outside Castle Station, having travelled from Rushden, laughing with others like me to hide our apprehension. Several army lorries arrived and a Corporal Carr, whom I had been at school with, alighted and faced us from fifty yards across the station yard. “That’s right, have a bloody good laugh now. It will be your last laugh for the next two years” he bellowed. So began a phase of life, which had been thrust upon me. I became resentful of the system but found friendships easy to form. We were handed out uniforms with little regard for size and shape. Haircuts were compulsory, regardless of need and the first meal was awful. Our kit had to be ‘bulled’ and some of it must have seen first daylight in the first world war. During the initial six weeks we had written tests and we were interviewed by the Personnel Selection Officer, who observed that I had some familiarity with the Old English Classics. He then surprised me by asking if I had ever thought about becoming an officer. As my ambitions in the army were to get home on leave away from the army as often as possible, I replied, “No Sir, I haven’t”. I was prepared to obey orders as the line of least resistance, but not to give them in the Infantry. We had an extremely arduous six weeks followed by Christmas leave. On Boxing Day our destination was Blenheim Camp, Bury St. Edmunds, our second training camp. Training and P.E. continued at Bury with a drill parade on Saturday mornings. At

From Bury we spent a few weeks at Roman Way Camp,

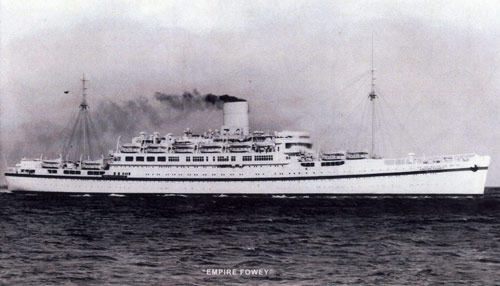

During the Bury/Colchester period we used to train in Thetford forest. Fingringhoe and Friday Woods were training areas where we first handled grenades. THE ‘EMPIRE FOWEY’ AND TRAINING IN THE FAR EAST. Our ship was the Empire Fowey and as we drew away, leaning over the handrail I spotted a family seeing a brother or boyfriend off – a mother, father, sister or girlfriend and a spaniel dog! They were unknown to me but I adopted them, keeping them in sight until they were too small and hazy to make out.

The Fowey weighed 28 thousand tons and had about a thousand of us on board. ‘Life Boat Stations’ was a daily chore, necessary, but usually chaotic. We used to get plenty of P.E. and lectures, some of the lectures were on

One morning in the

The first shore leave was at

We were in the

My memory of Columbo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) is the smell long before we reached it. The dockside poverty was desperate and elephantitis was common. We sailed southwards between the Malaysian peninsular and

After

We began to realize that we would eventually be on active service, but comforted ourselves that we would survive. However, when we were on active service events were such that, although optimistic I never took it for granted that I would ever return home. We sailed for

TRAINING AND IMPRESSIONS IN JAPAN. In Kure harbour was the largest vessel I had ever seen. It was the aircraft carrier HMS Unicorn. I also remember a dockside tower crane, which was made in England and could lift two hundred tons. We were destined for the Battle Camp at Hara Mura. We marched for mile after mile through unusually beautiful scenery, to take a three week course in two. Before we reached the camp which was guarded by former Japanese officers, we passed a large wooden inn. Its function became clear when we noticed naked women displaying themselves from upstairs windows. During the three weeks in Japan we had marched extensively. The simple houses were all immaculate, with highly polished floors, which could be seen through the open sides. The Japanese people looked wholesome and contrasted with the poverty and squalor of the Chinese people we had seen in Kowloon and the New Territories. Our two weeks’ course completed, we returned to Kure and prepared for our next adventure, which was to sail for Korea (THE LAND OF THE MORNING CALM). KOREA.

We marched out at night with full kit, a pick or shovel and extra ammunition to carry and boarded a convoy of American lorries. Then we were taken to various ‘jeep heads’ to the rear of each position, from which we staggered with our loads along the trenches to the fighting pits – recesses in the sides of the trenches to stand to and await events.

The enemies we knew of were basic in most ways. They would carry a supply of rice and could exist on little else for weeks. They were used to hardship and could stand more than we could. In the paddy fields on patrol, they were stealthy and quick whereas we could be noisy at times. However. Most of us learned by experience and as our lives could depend upon moving about quietly we certainly improved.

We were becoming used to patrols. Standing/observation patrols of three or four men would make their way out to no-man’s-land to sit still for two hours to observe; reporting back any enemy movements. The ambush patrol would consist of about fifteen of us. We would go out to where the enemy would be likely to move, to form an L shape formation. The fighting patrol would be of similar size but would go out looking for trouble. Regularly, we would experience heavy shelling and mortaring. Often, when we standing to at night we would have to resort to shelter at the bottom of the trench. We were in the First British Commonwealth Division and we were alongside the troops of many different nations. We noticed the Americans were supremely well equipped generally. The main decent thing we had was our late winter issue clothing. When we were up the front line American planes would arrive over the opposite enemy hill at about four in the afternoon with napalm bombs. For us it was like sitting in the front row of the cinema. The enemy lived under and behind the hills so not much damage could have been done to them. Fortunately, they never attacked us with planes. Always, on our position in the line we would display coloured rectangular markers. These were laid out on the ground forming different configurations each day to alert friendly planes we were there. In the winter we used to patrol in the snows, often with wet feet because of the shortage of proper patrol boots. A rum ration was available during morning stand to. For camouflage we wore loose fitting white pyjama like garments. Returning to our lines from one patrol we approached a finger-like spur of hillside where a Chinese body was discovered. Being careful of booby traps, it was searched and a letter found. This was later interpreted and published, and the similarity to our own incoming letters was remarkable. He and the family had the same hopes and fears and deserved better than to have him perish in yet another war. MEDALS. We were entitled to the British Korean Campaign medal and the United Nations medal. There was a parade and we lined up for the presentation to be made. The United Nation medal was complete and could be pinned on. However, and I thought it typical, the campaign medal was handed to us in a box. It was not complete and we had to assemble it ourselves later after adding a clip to it. Some comrades were presented with bravery medals but lots, who had carried out far more dangerous exploits, were not recognized.

PIMLICO. Pimlico was the code name of an operation carried out in

The operation was bold. Success or failure would result in casualties. In fact, young National Servicemen and Regulars had their lives changed overnight. I pay tribute to and have respect for all those who were involved. We all knew that our enemies were aware that such an operation was imminent. Consequently there was a two-day postponement. The attacking parties expected that the already alerted enemy would provide strong opposition. In view of this those on the operation embarked upon it burdened with this extra anxiety. We could hear the activity in the paddy fields and in the hills but could only guess at the number of enemy involved. We didn’t know that from the seventy or so who carried out the attack sixteen were killed, two or three dying from wounds. Twenty-one were wounded and eight were missing. For the next seven days volunteer recovery parties went out to establish the fate of our comrades. This resulted in six casualties so our task was not without danger. Those who had not survived were still in no-man’s-land and had been subjected to nature’s scavengers. The Royal Fusiliers had been in Korea for just a year. Our next destination was the Canal Zone, Egypt. OUT OF KOREA We sailed from Pusan on the Empire Hallidale on the 11th August. It was stimulating to see Pusan for the last time and be heading westward. The Hallidale was similar to the Empire Fowey on which we had sailed eastwards and we arrived at Kowloon on the 15th. We were back on the Hallidale to arrive in Singapore on the 28th. From Singapore we headed north through the Malacca Straits again, and sailed across the Arabian Sea to Aden on the tip of South Yemen where we had a short shore leave. We were over the Red Sea again approaching the Suez Canal where our destination was Kabrit Camp, where I spent a happy month. THE FINAL PHASE. Being only a week or two short of demob, thirty of us of the same intake lined up for a talk by the Regimental Sergeant Major. We were subjected to another ‘address’ because of our leaving the army. He said we were making a big mistake and added that we would have to pay a fortune to get civilian haircuts. Our transport to Stanstead, England was a four engined Avro York and staffed by very considerate A.T.S sergeant stewardesses. We had a short stop in Malta at night, and when we landed in England we experienced an icy blast of cold air through our Egyptian summer shirts when the aircraft doors were opened. An officious civilian police sergeant, who thought he was playing soldiers, treated us with contempt. Perhaps he suspected a criminal element amongst us and treated us accordingly. The original Royal Fusiliers amongst us reported to their department at the Tower Of London. I was directed to report to Quebec Barracks, Northampton where I had joined up in my parent regiment. I spent the night at home and reported in the next day. To my surprise and consternation I was told to draw out my bedding. On protesting that I had come to be demobbed I was told that I would have to see Regimental Sergeant Major Clements who used to ask us if the food was all right. Standing to attention I explained where I had been and that I had had leave in Tokyo and two or three short breaks away from the front line. I had the impression that he thought that I had had an easy time. He said that I could only have half of my entitlements. This was puzzling, and it turned out to be a five day pass. It was not long before I was home again in Rushden. I always resented the two years plucked out of my career but nevertheless valued the experience and the friendships that were formed. I had had a few narrow escapes, I think I was lucky, and remain thankful. CIVILIAN LIFE REGAINED AND SECONDARY EDUCATION INTRODUCTION. The second part of my ‘technical’ Teachers’ Certificate consisted of the Theory of Education and Teaching Practice. After the minimum of six months in schools, and then further study, I passed the final examinations and gained my certificate. This was an extremely busy period involving quite a lot of travel to different schools, but it was rewarding and very enjoyable. My first full time post was taken up in September 1954. Had it not been for National Service I would have started two years earlier. I was to be the woodwork teacher at Kingscliffe School, just south of Stamford.

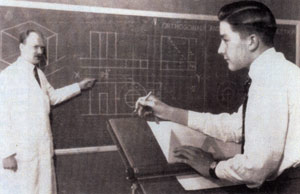

During my three years at Kingscliffe I embarked upon various technical courses and began to realise that I needed to become more academic if I was to become a Mathematics Lecturer. My present post was far from ideal for this. I applied for a Woodwork and Drawing position in Northampton where there was a large College of Technology, offering Mathematics and Science courses. This college is now the University of Northampton. CHERRY ORHARD SECONDARY BOYS SCHOOL 1957-1965. Cherry Orchard Secondary Boys School, with its engineering bias had opened in 1956, a year before I was accepted for the post. I joined a large, well qualified and talented team of staff.The drawing office had twenty individual drawing stations and was a large room with a big shelved stockroom. I quickly became acquainted with the workshop and motor engineering section where there was an old double decker bus chassis. For a time I enjoyed teaching basic metalwork as well. The boys took a four-year course from 11-15 years. Later on, although I regularly frequented the workshops I no longer taught there. Instead, I did some ‘craft group’ mathematics.The ‘craft group’ was slower but generally co-operative. Some of them had seriously learning difficulties. Drawing work used to be displayed on large panels in the office. Usually it was the best in the group each week. O level pupils were involved in Plane and Solid Geometry, whilst others made working drawings from the solids. Although a degree was in my mind I was too interested in the job to neglect anything from school by the continuing part-time study at the college. I had the confidence of the headmaster Jack Newitt and a great deal of freedom. If he thought you knew your job he would leave you to get on with your job alone. This situation led to a few extra activities including model engineering and science clubs.

Leaving seemed to be the obvious step for me if I was to progress further in my career. A head of Mathematics and Drawing post, in a

I applied, was interviewed and got the job. Unfortunately the travel was time consuming and expensive. Even the railway part of it became tedious.

The area was known as Little India and I remember a class of 11 year olds who only had very limited English with which to communicate. They were so keen and attentive that I felt privileged to be with them. Tom White, a former pattern maker for twenty years had joined the school at the same time after two years at college. During our many lunchtime talks he suggested that a

The course was at Rugby College of Engineering and Technology 1957-58. Travelling was reduced to a total of 40 miles each day. In the part 1 examinations I was only borderline in Physics so I thought that having had my opportunity I ought to get back into teaching. Before an opportunity arose in education I spent two or three months on freelance on hardwood, oak, joinery and building. SAINT MARY’S ROMAN CATHOLIC MIXED SECONDARY SCHOOL 1968. This was the school that became my first school back into education when I was accepted for general subjects. General subjects included Mathematics, History, Geography, Art and English. Mr Hobart, the Head of Mathematics was well established so there was no opportunity for promotion in that direction. A more suitable post became available nearby so after just one temporary term I applied for it and was successful. MOULTON SECONDARY MIXED SCHOOL 1968-70. The Headmaster was Mr L A Scott, an ex Gunner-Major in the army. The post was for Mathematics, Drawing and General Subjects. I was there for about two years and thought it was an excellent school for the pupils. During my two years there we had a speech and open day with a guest speaker Mr J L Mc Kinlay, the Principal at

KETTERING TECHNICAL COLLEGE/TRESHAM INSTITUTE OF FURTHER AND HIGHER EDUCATION 1970-89. Initially the college I knew was a modern three-storey building with basement workshops and an extensive complex of wartime prefabricated buildings. During my nineteen plus years there, two new larger buildings replaced the temporary part and several other large buildings in

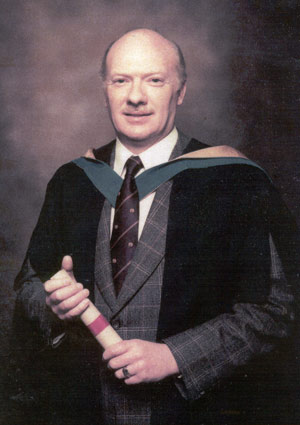

Owing to the development of the college many other changes occurred. We formed a Mathematics section of thirteen within the science Department. Statistics and Computing were also covered by us and we served both the Construction and the Business Studies Department. With increasing numbers of ‘O’ and ‘A’ level students, particularly in Mathematics, a separate Mathematics department was formed. We also taught ‘O’ level GCE Mathematics for the Oxford Certificate. Optional sections of the syllabus were Calculus and Modern Topics. I used to include these extras with some of the classes, i.e. mostly with Revision Groups. All of this was an excellent starter for ‘A’ level Mathematics and Science. Later C.S.E. was introduced alongside G.C.E. both to be replaced later by G.C.S.E., which had a more general syllabus suitable for everyday Mathematics. As a starter for ‘A’ level Mathematics, it lacked many essentials. We used to begin the ‘A’ level by filling in these important gaps, not covered in the G.C.S.E. examination requirements. For five years I was an Academic Board member and for ten years I was the secretary of the Mathematics Study Group. I was also a member of several committees and I was involved with many seminars. Generally, meetings would be preceded by several ‘papers’ to become familiar with and end with lots more to digest. Doing justice to it all would be a full-time occupation even if I didn’t have to teach. I certainly preferred teaching to administration. When I was first a lecturer at Tresham I was fortunate enough that my colleagues in the Mathematics Department were very helpful to me. My academic background was not the equal of theirs and I found myself in the midst of a great deal of experience and talent. I graduated in Mathematics in 1977 after gaining six credits in nine different courses with the Open University. I was one of the first O.U. students and we had to cope with the initial courses. We were also tutors of about a dozen students each. Most of the ‘A’ level students progressed to University or other Higher Education establishments. We needed to prepare them for that and have close contact with some of the staff in these establishments. Many students were from the Far East and some of the Hong Kong Chinese were particularly bright.

A friend, Reg Payne, was the Senior Technician at Tresham College. During the war he flew 30 missions as a wireless operator on Lancaster Bombers. In a disatrous scheme those who could bailed out at 6000ft. Reg was the last to exit and on tears and prayers he reached 3000ft before he could open his parachute. The rectangular ring from the parachute adorns a wall in his hallway at home. His skipper on the scheme, with whom he has regular contact is Sir Michael Beetham, who became Marshall of the Royal Airforce. RETIREMENT. Eric Baxter, another friend, was the Head of the Science Department. As the bureaucracy increased generally in the profession he felt that he had had enough so he resigned fairly early from his well-paid position. He was the caller at the college folk dances and alongside Beryl they did a great deal of charitable work for the Anglican Church. I was privileged to work with such people in education and I often thought of those from whom I gained so much when I was an apprentice. Given present day opportunities many a humble craftsman might have been a highly regarded and well paid professional. By 1989, when I retired early at the age of fifty-seven, there were fewer students from overseas and the local high schools were producing more intensive courses for their pupils. Consequently we experienced a gradual shortage of students. As I had always various projects in mind and some of my holidays had been about about ten or eleven weeks long per year I developed a feel for retirement. I had been at the College/Institute for over 19 years Over the years I did a lot of voluntary supplementary work to enhance my classroom activities. However, as I became more experienced, my unease about the ever-increasing number of politically motivated directives (which did not seem to me to have the right emphasis) also increased. I have to say that most of my teaching colleagues felt the same. I didn’t agree with many of the changes so it was time for me to go and I was grateful to be able to go with ease.

Memories of the bomb in 1940 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||