|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clive Wood, 1999 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Architectural History

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Essay Autumn Term 1999 Clive Wood - 2nd Year |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Industrial buildings are not so much architecture as an embodiment of architectural embellishment A statement that is surely true of the industrial buildings associated with the boot and shoe industry, at least in Rushden and adjacent towns, in fact it appears that even in Leeds and Manchester the footwear industry rarely aspired to architectural creations to house their manufacturing activities. However while most factories of the late nineteenth, early twentieth century are variations on the standard brick box, lit by varying numbers of cast iron windows with a functional entrance on the ground floor and a loading door on the top floor, some owners did show a desire to give their factories a limited individuality by embellishing them with some decorative features. While there are exceptional examples such as the Art Deco factory of Sears in Northampton the footwear industry never commissioned buildings in the grandiose manner to compare with the Bliss's Tweed Mill at Chipping Norton. In Rushden there are a number of examples to illustrate the embellishment theory, though the definition 'to beautify' is perhaps slightly exaggerated. In Rushden there were three, now regrettably only two factories, with 'turrets' or what might be called Scottish 'Baronial' and while there is almost certainly no connection with Rene Mackintosh, his work must at some time have sown the seed for their creation.

The half storey consists of recessed semi-circular trimmer arches on brick and stone string courses, surmounted by brick cornices before the springing of the roof. Most of the architectural detail is included in the comer, though there are some features on the facades to left and right, these are divided by a corbel course between the first and second floors which terminates at each end with a small pediment of corbel brickwork and on the third and fourth floors 'pilasters', consisting of two stretchers and a header brick in width, divide the wall into vertical panels, into these are inserted single window openings on the ground, first and second floors of shallow camber gauged arches and on the top floor pairs of windows with strait lintels.

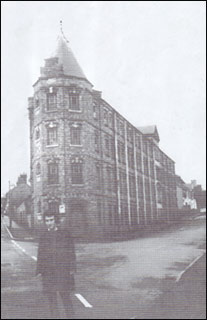

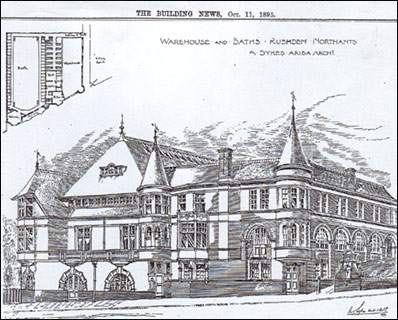

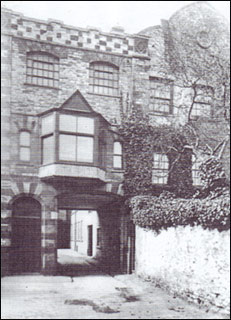

The third factory 'turret' is a variation on the design, in as much as it is circular with a true conical roof [Fig 4]. Like Green's it starts at first floor level but over a recessed door rather than a window and unlike most of the other factories in Rushden has a pedigree, being the only portion built of a grand scheme designed in 1895 by A Sykes, ARIBA., to provide indoor swimming baths and a warehouse for Rushden, a strange combination although perhaps way before its time, with private enterprise supporting a public facility. The portion that was built did eventually provide something akin to that ideal with the ground and first floors being a leather merchants and the top floor, from 1935, the YMCA. In this instance we have again the use of red brick with detailing in 'whites' with a stone abacus to the brick pilasters and stone lintels to the top floor windows forming part of a facia beneath the roof line, the use of white headers set forward to form a dentil course beneath the stone sills of the semi-circular windows and the roof of the turret and as labels beneath the abacus is a simple but attractive feature, the extrados of the window arches being a larger version of those that form part of both Green's and Jaques & Clarks premises. [Fig 4a]

By the early 1900's Rushden had over fifty shoe and allied trade premises and even now over forty still exist, though only three as production units, they range from William Green's first factory of 1872 to John White's 'Daylight Factory' of 1937, the later built to the design of Professor Albert Richardson is now a Grade II listed building, though sadly neglected. Whilst the product of an architect of National importance it would be difficult to attribute the design to any particular influence, other than the Thirties desire for simple clean lines and as indicated by its title, 'daylight factory' a desire to use natural light, though of course this had been achieved for many years with north facing roof lights, and that without the pedigree of a nationally known architect. It is possible to see within many of these buildings an attempt, however small, to make a statement about the aspirations of their builders, most shoe manufacturers started life as 'workers', usually clickers, the 'cream' of the trade and one can make interesting comparisons between the factories and the residences of these self made men, often their home was close to the factory even attached and by today's standards were imposing, not to say pretentious, some have gone, many remain and in themselves show a good range of middle class housing of the late nineteenth early twentieth century.

In the old style of building is the factory originally of Cunnington Brothers in Crabb Street, a building that might be called pretty due to its brickwork being in single Flemish bond, particularly attractive when done with red stretchers and white headers, with the segmental window openings in red brick and blue brick sills the exception are the 'office' windows, being large three light sash windows surmounted by plain pediments,[Fig 7], a slightly more refined version of this is to be seen on premises of Bignell's in York Road, [Fig 8]. As with the office windows at Cunningtons, so it was necessary to differentiate between the entrance for the workers or staff and the doorway represents Rushden's attempt at a Gibbs surround, [Fig 9]. Another building, that of Denbros in Rectory Road, brings together embellishments in gay abandonment, with quality red brick and stone pilasters, framing and dividing another Flemish gable, this one with a stone cornice and narrow vertical shafts of stone, a bullseye window forming the central feature of the gable. Blue diaper brickwork in diamond patterns of varying sizes enlivens the elevation, [Fig 10]

Two doorways differentiate between staff and operatives, the latter with narrow wooden pillars with rebated panels, small capitals and abacus under narrow panels decorated with a diamond pattern, a segmental head to the door recess with keystone and spandril, in the spandrils a crude form of strapwork decoration [Fig 11]. The second and obviously principal door is somewhat larger and has a Baroque feeling with its wide architrave surround, a fanlight of balusters and a broken pediment and cornice to complete the creation [Fig 12]. As an example of restrained decoration, the factory of Walter Sargent in Crabb Street is a good illustration, very much a brick box of three and a half storeys, it incorporates a number of refined details. The windows with chamfered jambs and arches with stop-ends three courses above the sill are quite unusual and enliven an otherwise standard window opening, a blue brick string course at all levels of the windows which follows their segmental arches is again a nice detail and compliments the blue brick sills on matching brackets, add to this the four courses of corbel brickwork and you have a good example of an industrial building as an embodiment of architectural embellishment. Of course if we look at the design of modern buildings, by comparison, even the plainest of Victorian or Edwardian factories can contain the equivalent architectural input of some of the simpler eighteenth century mansion if not their more flamboyant predecessors. Reference sources:

Tutor's Report at end of term: Essay: Industrial buildings are not so much architecture as an embodiment of architectural embellishment. A very good essay, with excellent descriptions and, on the whole, competent use of architectural terms. The examples were relevant to the title, and you demonstrated an admirable perception of details and architectural styles. It is a pity that, based on the comprehensive evidence in the main part of your essay, you did not write a better conclusion than the single sentence which ends your essay. Your introduction was very useful in showing that the essay is focussed on boot and shoe buildings in a particular locality, viz. Rushden, and that you were aware that the normal definition of embellishment involves "to beautify". I was interested in your choice of the three factories with turrets as your starting point. They are certainly examples of an architect's influence in "turning a corner" rather than having a plain corner and I wonder if this matter of "turning a corner" has been dealt with elsewhere on the course, since its effect is quite important in the urban situation. Apart from this architectural aspect, what other function did the turrets serve ? Stairs ? Your statement that Rene Mackintosh's "work must at some time . . ." would be hard to justify and I suggest caution by using probably instead of must. Only one of the three factories has a conical roof to its turret (By definition, a cone is on a circular or other curved base). For the roof of the turret at William Green's "an eight sided stunted spire" might be a more appropriate description. The sketch at Fig. 2 is very useful. I appreciate your analysis of the Jaques & Clark building identifying similarity with some details of the Green's building. Regarding your description of the Lilley & Skinner building, there are two terms which do not seem to be used correctly: Abacus is usually used for the flat slab on top of a capital whereas impost is the normal term for the block or band from which an arch springs; Label is an alternative name for hood-mould, a projecting moulding above an arch or lintel to throw off water. John White's 1937 building is evidence of architecture of the whole building and a fuller description could have been used to balance your discussion which concentrates on the embellishment of facades, for example your excellent description of the front of William Claridge's premises. Your attention to window and door details, as recorded in figures 7 - 12, is impressive. If only more people, including planners, took notice of these they would see boot and shoe factories are interesting and worth looking after. I am particularly attracted by your final analysis, that of Walter Sargent's factory in Crabb Street. At first glance this building seems to have nothing to offer in the discussion of architecture v embellishment but, as you point out, its public sides are enhanced by "refined details". Is it possible to see if these details are to be found on the non-public sides ? I have found this essay enjoyable, as well as interesting, to read and hope you enjoyed your exploration of these often-overlooked buildings. Geoffrey Starmer Note: Clive received a high mark for this work. Click here for more about Clive |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||