Evening Telegraph, Monday, July 23, 1956

His Dream Dairy at Last - A 23-year-old ambition is achieved - The dream fulfilled

For 23 years Mr. Donald Summerfield has wanted to build the perfect modern dairy. He had good premises at Rushden for many years, but they were not exactly what he had in mind. But now, at 43, his "dream dairy" is opened—at Irthlingborough.

|

|

The new dairy at irthlingborough

|

From the road, which leads into the A6 by-pass, the dairy with its red brick front, net curtained windows, bright yellow paint and geraniums outside the door, could be a block of modern flats.

|

|

Some of the vehicles in the loading bay

|

Only the loading bay, hidden discreetly at one side, and the clatter of hundreds of bottles being loaded, gives away its purpose. .

|

|

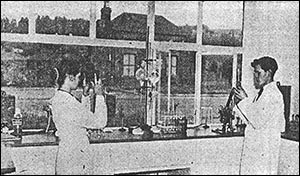

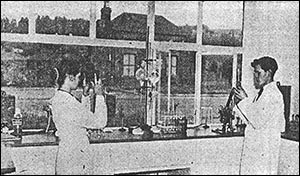

June Summerfield and David Luck in the laboratory

|

Through the front door, a pastel shade corridor with plastic flooring, leads to modern offices overlooking the road and the laboratory—realm of 18½-year-old Miss June Summerfield.

It is here that Mr. Summerfield's daughter reigns supreme. After two years of study, she has taken over the complex work which ensures that every bottle of milk is up to standard. It is no easy task. There there is no rule of thumb.

The ingenious instruments of the scientific backroom boys have their place here just as much as in modern industry.

There is an incubator to attempt to grow "germ" cultures on bottles—as a precaution against their being dirty. There is all the necessary equipment to "mount" the bacteria on slides if they do grow, and a microscope to identify them.

There is a centrifuge, so that the butter fat of the milk can be tested, for it must never fall below the specified standard. There are instruments for testing the success of pasteurisation (the process by which milk is made germ free) and gadgets for this, and gadgets for that.

But this laboratory is only a side issue. It exists only to ensure that everything in the main plant is up to standard. It seems strange that after all this scientific equipment of the 1956 dairy, the first test that the milk gets as it enters the weighing tank is purely physical.

|

|

Mr and Mrs Summerfield with their daughter June, who is charge of the laboratory, and their son Gordon, who is learning the “bacteriological” side of the business. They have another daughter who is a nurse, and also two

young children, aged nine and seven.

|

Smell it

It is somebody's job to do exactly what the housewife does—smell it. Old-fashioned it may be, but this test is one of the most effective of all for though a pint bottle might be "off" without smelling strongly, a whole churn full soon makes its presence obvious. Needless to say, a churnful of milk which is "off" never enters the tank. In fact, it never enters the dairy.

The milk, already filtered by the farmer-supplier, smelled as a test for freshness and weighed, is pumped through stainless steel pipes which shine like the instruments in a doctor's surgery. There are 3,500 gallons of milk a day going through that intake pipe enough to fill something like 28,000 bottles.

Understatement

Something happens to the milk after that. To say that it is pasteurised is an understatement. Only an expert can understand exactly what goes on under the surface of pasteurising plant, another stainless steel wonder which could have been designed by a space fiction artist.

The milk goes into a shining pan at a predetermined rate. It is filtered and raised to a temperature of 162 degrees for just 15 seconds being filtered a second time in the process—in filters which are changed every half-hour.

|

|

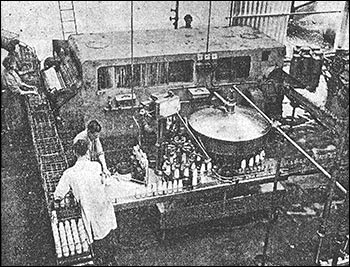

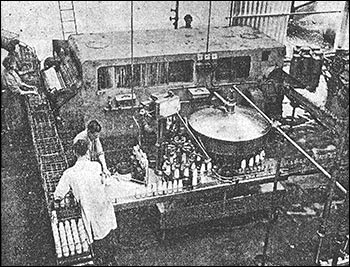

Inside the bottling plant

|

If through any reason the milk does not reach the proper temperature, a bell rings, and it is automatically fed back to the beginning of the line, to go through the process again.

And all the time exactly what happens is automatically recorded in coloured ink on a revolving graph.

The processed milk, at about forty degrees, passes into one or two stainless steel storage tanks which are washed out alternatively, during the day.

Other stainless steel pipes lead straight to the bottling machine.

But before milk can go in bottles, the bottles must be clean. They are fed, about a dozen at a time, into a giant box-like container. They appear shining clean at the other end to stand like soldiers on a moving belt and march in single rank to the robot bottler.

It is here that engineering ingenuity is seen at its best, the bottles march into line along the moving belt. A simple "cog" picks them out, places them in the exact spot on a small lifting table.

A rubber nozzle comes down on top. The vacuum pump whirrs. And the bottle fills with milk.

A roll of aluminium foil is die-punched into bottle caps. A flick from a metal arm and it is resting on the top of the filled bottle which is now marching away to another section of the machine.

Some of the problems

IF you ever think of entering the dairy business, here are some of the problems that have to be overcome.

Dirty bottles: "We rinse, wash and sterilise all our bottles," says Mr. Summerfield. "But there are some bottles which come back in such a condition that they are not worth bothering with. We cannot wash them; it would take too long. They simply have to be broken up."

Cement is one of the main problems. Bottles used on building sites— and apparently builders drink a lot of milk—invariably appear to have been thrown on the cement heap.

The cement sets, and can only be chipped off. Sometimes it is not obvious until the bottles have been washed. That means more waste.

Lost bottles: What do people do with milk bottles? Somebody seems to be hiding them. About 100 gross of new bottles have to be bought every month to make replacements.

|

One gentle steady movement and the top is sealed on.

Men stand by as the filled bottles march off. It is their task to fill the crates which are ready on rollers and push aside any bottles that do not pass inspection.

Back again

In some cases the top has not settled properly; occasional bottles are not properly filled. When this happens, the milk is tipped out to find its way back through the whole system again like a schoolboy who is sent back to the lowest form to begin again.

Among the staff at the dairy are two young Americans, who recently left Wellingborough Grammar School. Their father is an American Serviceman and soon they will be returning home. In the meantime, they help pay for their "holiday in England" working it the dairy.

Some bottles are broken in the works, but very, very many are un-traced.

"If people would look after the bottles we should be a lot better off," said Mr. Summerfield. "And milk would be cheaper, definitely."

Some of the crated milk is required immediately, but so that the process can go on throughout the day, and supplies be ready for early morning delivery, there is a great cold storage room. But the milk never stands there for very long.

Manager of the dairy is Mr. Albert Lodge, who came to Irthlingborough from Boston three months ago, after 20 years of dairying in the North.

|