|

|||

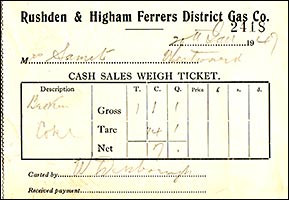

| Evening Telegraph, 26 September 1947 transcribed by Greville Watson |

|||

|

£95,000 GAS PLANT BUILT IN 2 YEARS

Rushden's Biggest Post-War Scheme |

|||

|

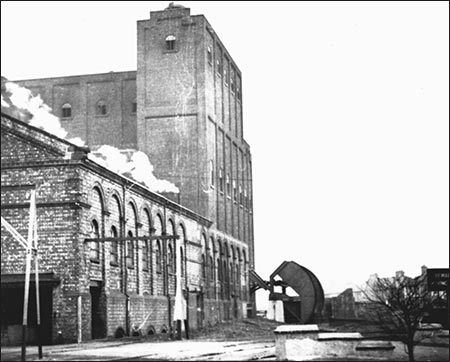

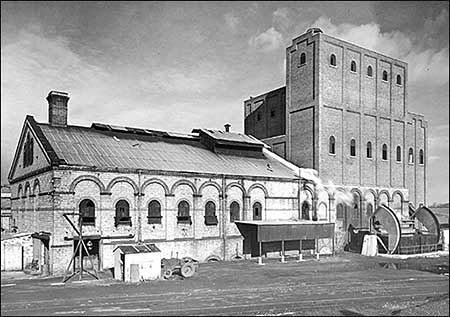

Rushden’s biggest post-war reconstruction job has just been completed. All coal gas used in Rushden, Higham Ferrers and Raunds comes from new plant which has taken two years to build at a cost of £95,000. To be strictly correct, the work accomplished is one stage of a scheme. Production of gas has been multiplied by three in Rushden District Gas Company’s first major development plan since 1916, but distribution is another big question which will be tackled as soon as possible. One hundred feet high and outstanding in the skyline of the town, the new gas-making unit – a house of retorts and other plants – has been grafted on to the old. The new section, rising high above what remains of the old, gives an immediate picture of the change of system – from horizontal retorts to the latest vertical type. It forms a case around a row of retorts, the intervening space being filled with working stages and secondary apparatus. |

|||

|

Poured Like Sugar Out for the story of Vulcan’s new domain (writes our reporter), I began with the entrance of the coal – a rapid, if undignified, entrance by the aid of a 20‑ton wagon tipper outside the walls. Already in position on a metal platform, a railway wagon was thrust up to the desired height, gripped by massive metal arms and turned slowly almost head over heels. The coal poured out like sugar from a packet until the last pieces had raced into the receiving hopper. I saw the truck restored to ground level, and trundled away on the lines by a converted farm tractor. The coal it once held had gone underground and into the building. I followed by a more comfortable entrance, found the coal moving in on a conveyor, and saw it going to the top of the works at the rate of 40 tons an hour. An endless chain of ‘buckets’ was doing this job with the smoothness of a tube escalator. It works vertically, however.

|

|||

|

Rushing Up Following to the top by ordinary electric lift, I stepped out into an exciting, if dusty, province where the coal drops out of the buckets, glides forward on a band conveyor and is disgorged into four hoppers, each holding 40 tons. Each hopper forms a feeding funnel pump over the top of four retorts – there are 16 retorts in all. The views of Rushden, Wellingborough (and beyond), Finedon water tower, and other landmarks from this top deck are surprising. The lift took me down one stage to the main operating level – “top of stack,” I heard it called. Here I remember looking through some Pyrex glass panels to see liquid (they call it liquor) rushing down the inside of very fat pipes. There was also something cloudy and yellow rushing up the pipes, and this proved to be the town gas streaming away from the retorts below. The spray of liquor is important – it prevented tar from sticking to the pipes and keeps it flowing until it reaches the tar tower (25ft high, 4ft diameter), where it is dropped and at intervals run off. |

|||

|

A Day Off Next discovery was the very vital retort house governor which controls automatically the business of drawing the gas from the retorts. I then enjoyed the sensation of looking down a retort – down through a red glow to the base 25ft beneath. It appeared that this retort was having a day off for “scurfing” – which is a burning off of the carbon skin which forms on the bricks. Ten of the 16 retorts are in use – the whole plant has a big reserve capacity – and of the ten there is usually one “off” for scurfing. The hottest spot in a retort is about one-third of the way down – a matter of 1,300 degrees centigrade or 13 times the temperature of boiling water. Inspired by this information, I descended grimy steel stairs and arrived on a platform opposite the combustion chamber inside which the retorts are roasted. The space between this outer wall and the retorts is hotted up to an incandescence by the burning of “producer” gas.

|

|||

|

Felt The Heat My guide and informer, Mr Tom Watson, the engineer and manager to the Company, took up an iron rod and removed a plug for a peep through a sight hole. I saw the incandescence all right – felt some of it, too. Getting down to ground level, I found the producer gas being generated by furnaces which are fed by part of the coke produced in the plant – a definitely unvicious sort of circle. Waste producer gas is drawn off from the top of the plant and with goes up the big chimney which juts over the building or down a flue back to ground level, where it operates two waste heat boilers – each the size of a railway engine and able to produce 2,000 lbs of steam an hour. Boiler tubes do not like Rushden’s hard water, so these are appeased by a new type electrical softener which pulverises particles in the water. The steam from these boilers has many uses: it is used by the extractor driving engines, drives the liquor circulating plant, and is admitted to the bottom of the retorts for the automatic production of water gas. Surplus steam is used for power in the remainder of the works. The extractors already mentioned are at the bottom of each retort; they are slowly rotating “star” wheels – making one revolution in three hours – which hook the coke away continuously. Coal, I was told, becomes coke about halfway down the retort. The coke falls into a chamber (still gas-tight) and is finally discharged, black and cold, in two‑hourly instalments. Surprisingly, the coke has now to visit the top of the building. It goes up in the bucket conveyor – or will very shortly when the contractors have finished certain outstanding work – and rides on a band to the coke-screening plant where it is jigged through screens and sorted out according to its size. Passed out of the building through hoppers, it gets a final de‑breezing on its way to the merchants’ lorries. |

|||

|

Only Three Men Having seen all this, I was wondering hard about the operating staff, there being little sign of it. The answer was that only two men and a foreman are required for each shift in the retort house. As gas production goes, they work under good conditions. There are no open flaming doors, and machinery does the heavy work. Elsewhere in the works I saw a new booster house where fresh equipment includes steam-driven compressors which send gas to Raunds. At the meter house an outgrown “station” meter had been dismantled and a modern meter of twice the capacity but one-tenth the size was awaiting installation. Washing a pretty black pair of hands in the managerial office, I was told that the works were built in 1892. I inquired about the future use of the now surplus retort space and learned that it will be transformed into stores, workshops and messrooms for the employees. |

|||

|

|||